Australia’s move to cloud-based technologies can’t afford to repeat the mistakes of the early adoption of the internet and social media. At first, those earlier developments were not seen as critical infrastructure or technology that needed protection to defend a nation’s citizenry, security and sovereignty.

Reaping the innovative benefits of cloud computing in a way that does not leave the nation less safe requires a clear and enforceable model of shared responsibility for cloud security. Individual roles should be well-defined, obligations understood and accountability embedded at every level.

Cloud computing, and other such tech, is a necessary part of our growing artificial world but naturally introduces new threat surfaces, systemic risks and critical vulnerabilities across government, industry and civil society. These risks can temporarily affect our economic security, but mismanagement will erode public trust and, therefore, more permanently threaten our national resilience and sovereignty.

Democratic governments’ early unwillingness to interfere with innovation has led the internet and social media to be dominated by authoritarians that have been all too willing to stick their fingers in, exploiting the technologies for propaganda and interference. China and Russia are the main culprits in this.

We must not keep making the same mistakes. For a start, we should consider how providers, customers and governments each contribute to individual benefit and collective security.

Too many cloud users operate under the assumption that the provider alone is responsible for security; conversely, providers and users too often remain complacent, believing that the government will step in during a crisis.

Providers should be held accountable for securing the infrastructure layer, physical data centres, networks and virtualisation platforms. Customers remain responsible for securing their data, configuring systems properly, managing user access and maintaining operational readiness. And governments should use minimal regulation to protect the integrity of the infrastructure, specifically from foreign adversaries.

A shared model isn’t optional; it’s the only way to reduce risk in modern cloud environments. Failing to uphold these responsibilities has already led to serious breaches, including exposed credentials, unsecured databases and inadequate incident responses.

Failure to develop national policies has also led to inconsistent regulation of critical infrastructure and technologies. This has seen China dominate too many sectors on which society depends, such as renewable energies and batteries. We never gave Moscow control of our technology during the Cold War, so why are we so readily allowing Beijing to do so now?

The director of the US’s Cyber Defence Agency, Jen Easterly, argues that systems need to be secure by default, meaning they’re configured with maximum-security settings at the time of delivery. Furthermore, secure-by-design—in which security is architecturally embedded—cannot just be a mantra but should be a fundamental default principle.

Although cybersecurity is an ongoing process, protections such as encryption, system isolation and automated patching must be embedded during the design and deployment phases rather than being added after systems are live. Retroactively securing an environment leaves too many gaps and effectively means endlessly responding to one threat after another.

This requires cloud providers to be able to demonstrate, through independent audits and transparency, that their platforms are secure, resilient and capable of withstanding sophisticated and evolving attacks, including being able to recover quickly. Customers must be confident that the infrastructure supporting their data is not just compliant but protected and resilient.

Strong security governance is essential. The Department of Home Affairs’ Hosting Capability Framework is a certification scheme for datacentres and cloud suppliers that provides users with protections and assurance of security, including relating to foreign ownership, control or influence risk, at both the infrastructure and platform layer. Cloud providers must also have clear, operational frameworks aligned with recognised standards, such as the Infosec Registered Assessors Program run by the Australian Signals Directorate or the International Organization for Standardization’s ISO 27001. And they must be able to show how those controls are implemented in practice.

With governance and regulation in place, customers need to apply their policies for how data is handled, how access is granted and how workloads are managed. Most cloud breaches still result from users failing to apply basic governance and control measures. Resilience depends on customer readiness. Organisations need to design for failure, ensuring they have backup systems, recovery plans, continuity procedures and communications plans that have been tested under realistic conditions. The question is not whether disruption will occur but whether systems are ready to recover when it does.

Sensitive data should be encrypted by default, both at rest and in transit. Organisations should know where their data is stored, which jurisdiction’s laws apply to it and who has the ability—legal or technical—to access it. This is particularly important in national security or critical infrastructure contexts, and any providers unable to offer this level of transparency and control should not be entrusted with such high-risk workloads.

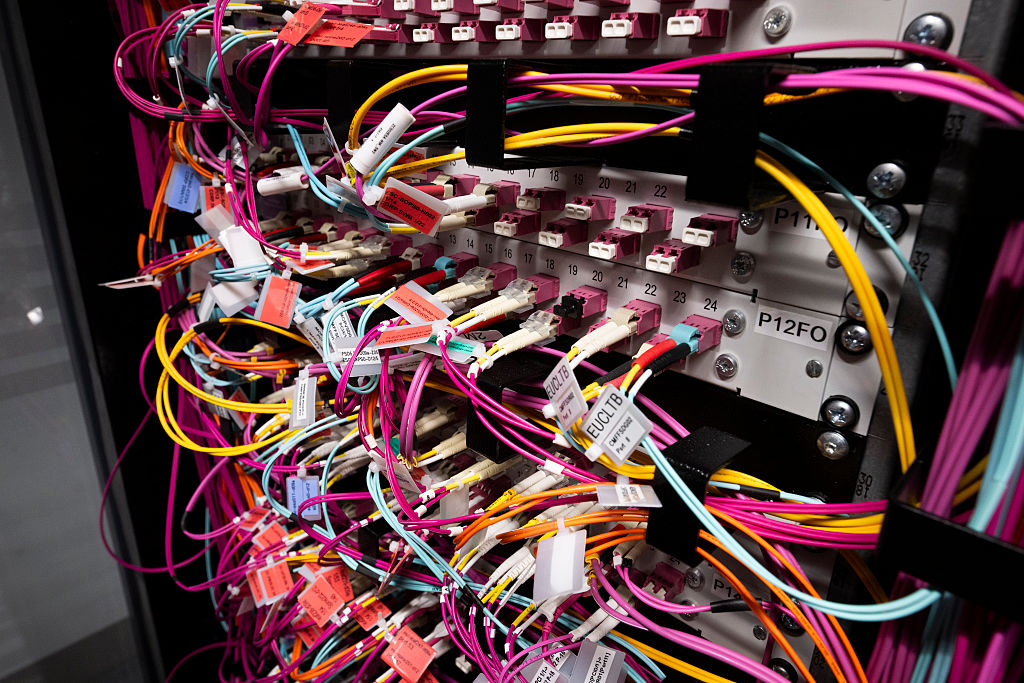

The physical layer supporting cloud environments cannot be ignored. The ephemeral-sounding ‘cloud’ is formed by physical infrastructure—data centres, cabling, hardware and energy systems. For Australia, government policy on critical infrastructure systems should, by default exclude providers whose supply chains create a risk of China accessing or controlling data and platforms. Then, providers must have strict physical security measures in place: controlled access, surveillance, layered perimeters and staff vetting. These controls must be demonstrable. If a provider cannot meet basic physical security requirements, it should not be hosting sensitive data or services.

Security doesn’t stop at the perimeter. Cloud environments must be continuously monitored for anomalies and threats. Providers should offer real-time monitoring, automated threat detection and built-in response capabilities. And customers have a responsibility to configure and monitor their environments and to act quickly when alerts are triggered.

Access control remains the most frequent point of failure in cloud environments. In the absence of a physical perimeter, identity becomes the new security boundary. Providers must enforce multi-factor authentication and role-based access controls. Customers must manage identities carefully—granting only the minimum necessary access, rotating credentials regularly and auditing behaviour for anomalies. A single compromised identity can compromise an entire environment.

As cloud use becomes more complex—spanning public, private, hybrid and multi-cloud systems—security oversight needs to evolve. Fragmented cloud environments create blind spots. Visibility, accountability and control must extend across the full cloud landscape.

Australia’s digital future depends on having reliably secure and resilient digital systems. That future cannot be delivered without shared responsibility. Government, providers and customers each have clear roles, and each needs to be accountable. Trust in cloud systems must be earned and continuously verified. Security as a secondary afterthought only puts the entire nation last.

Oracle is supporting publication of this series of articles. The authors are responsible for the content.