RMIT University and Australian diagnostic company Nexsen Limited have teamed up to develop point-of-care blood tests designed to identify acute kidney injury hours faster than current methods and, for the first time, to allow chronic kidney disease monitoring at home. Currently hard to detect in very early stages — when intervention is critical — almost a third of intensive care patients develop acute kidney injury, and an estimated 13% of people are living with chronic kidney disease, which remains a leading cause of premature mortality.

Currently, detecting kidney injury relies on testing kidney function, such as the ability to filter out creatinine. Yet, as creatinine build-up takes time, it can take hours or days to detect a noticeable difference. “Changes in the kidney function lag the damage to the complex structure of the kidney,” said Professor Shekhar Kumta, a clinician experienced in managing kidney failure in trauma and complex surgical patients, and Head of the Clinical Translational Research Partnership between RMIT University and Northern Hospital.

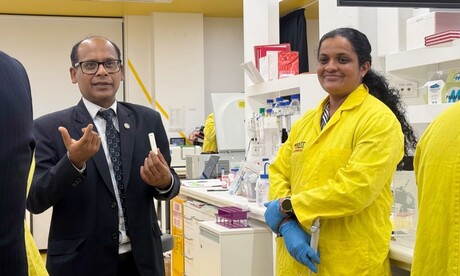

Sanskruti Lakhotia from RMIT’s Sir Ian Potter NanoBioSensing Facility holds a bottle of the nanoparticle formula being used to develop Nexsen’s kidney diagnostic tests. Image: Supplied

“A new test that can directly investigate the damage to different parts of the kidneys will be a real game changer,” Kumta added. “These new blood tests will be able to diagnose the root cause of the acute kidney injury early, which will play an important role in more clearly defining the optimal clinical management plan for patients.” The team are also developing patented DNA aptamers, which detect specific biomarkers associated with structural kidney damage.

“The current testing of kidney damage based on reduced urine output and increased serum creatinine levels can take six and 24 hours respectively, while our ultrasensitive diagnostic technology aims to detect damage much earlier,” RMIT’s Professor Vipul Bansal said. When customised for at-home regular monitoring of chronic kidney disease, researchers believe that similar tests could help more than 850 million patients worldwide, with the potential to sit alongside the blood glucose monitoring many diabetics use as part of their daily routine.

Top image caption: Professor Vipul Bansal holding an early prototype of the kidney test in the RMIT labs with research team leader Dr Pabudi Weerathunge. Image: Supplied