Chris Eubank Jr’s eyes betray nothing but everything all at once. They are expressionless but meaningful; cold but thoughtful. Even through the pixels of a computer screen, one can detect both pain and hope.

The 36-year-old is speaking from his adopted home of Dubai, having spent the past week in Brazil hanging out with his friend Neymar, the global football star. Whether travelling in secure convoy or by helicopter, Neymar showed the boxer around São Paulo, the trip leaving a mark on Eubank. ‘It’s impressive to see how much he’s loved in that country,’ he says. ‘He’s like a god out there.’

But the fighter is not a football fan – the two merely have similar interests, having met at a poker tournament in Spain a few years ago. ‘We’ve been good mates ever since,’ adds Eubank, talking via Zoom from a spacious apartment where he is surrounded by neutral colours on the walls and curtains.

What to read next

It was years before meeting Neymar that Eubank was first introduced to the appeal of poker. In the boxer’s home town of Brighton, a young Eubank visited the Grosvenor Casino and had no idea what he was doing.

‘I jumped in at the deep end. I would buy in for 50 quid, and if I won 10, 20 quid, I was over the moon,’ he smiles. ‘I was like, “Wow, this is amazing”. Then I was losing, week after week, and eventually I kind of just figured it out.’

Now Eubank sits at tables where the buy-in is £30,000 and has won as much as £350,000 in a hand. ‘I’ve come a long way from the £50 buy-in in my local casino in Brighton, that’s for sure,’ he chuckles. But, asked about his passion for ‘gambling’, Eubank takes exception to the term. He is big on skill and intelligence, not luck.

‘I don’t like that word, “gambling”,’ he shrugs, using his fingers to invert the commas. ‘To me, gambling is going to a casino, going to a roulette table and saying to yourself, “My daughter’s birthday is on the 19th. I’m going to put £1,000 on 19.” You put your £1,000 down, the guy spins the ball and you’re sitting there praying. That is gambling. I don’t do that.

‘Gambling is when you’re playing against the casino: blackjack, roulette, craps, baccarat, slot machines. When you’re playing against the house, the house always has the edge. In poker, you’re playing against your peers, your mates. In my case, I’m playing against non-professional players, so there’s no massive edge in anyone’s favour. It’s a game of skill, of reading your opponent. It’s a game of deception, bluffing; having a poker face.’

With that, Eubank points out how some abilities are transferable from his profession as a prizefighter. The similarities don’t end with the need for a good poker face. It’s also “the heart pump,” as Eubank calls it.

‘I get that in a big hand where I know I can win or lose a lot of money, or I’ve got to make a huge decision,’ he explains. ‘I’ve got to decide if this guy’s bluffing me for 100k or I’ve got to put 100k in, and I’ve got nothing and I’ve got to wait to see if he’s going to fold or call.

‘These are all positions where your heart’s racing and you’ve got to keep that poker face, just like in a fight when you’re hurt or you’re cut. You can’t show emotion. You can’t let anyone know what’s going on in your head and what you’re really feeling.’

Eubank thrives on walking the line of intensity between pain and joy. He trod it finely in April when he won one of the fights of the year against Conor Benn in front of 67,000 fans at Tottenham Hotspur Stadium.

The sons of British boxing legends Nigel Benn and Chris Eubank Sr shared a violent and pulsating 12-round battle that saw Eubank take victory – then spend the next two nights in hospital recovering.

The bout had been two and a half years in the making, after Benn’s failed tests for performance-enhancing drugs saw the grudge match postponed when it was just a couple of days away in 2022. They will fight a second time on 15 November, at the same venue.

Eubank expects the rematch to up the ante on an already intense rivalry.

‘People don’t change overnight,’ he says. ‘[Benn’s] an emotional guy. He has hate in his heart that’s not all of a sudden just going to disappear, so I imagine we will get that same energy.’

Eubank momentarily considers whether he might go so far as to say he enjoyed playing his part in one of the year’s toughest contests.

‘Do I like it?’ he says, more to himself. ‘It’s my life. After you do something a certain amount of times, it becomes second nature, even if it’s painful and dangerous. When you’re in those positions you’ve trained all your life for, you know how to get through them. I’ve built up a tolerance so I can thrive in those pressure-cooker moments.

‘Do I enjoy it?’ he asks again, talking about his profession as a whole. ‘Boxing is not a sport you can do if you’re not fully invested. As soon as you fall out of love with the training and the fighting and the preparation; with the food, the weight cut, everything; as soon as you start second-guessing, “Why am I doing this?” you’re never going to make it. You’re going to get hurt.

‘You can’t just like boxing, you have to be obsessed with it. It’s not about enjoyment. It’s my job. It’s what I’ve got to do to prepare my body for war’

‘I enjoy great food. I enjoy a great sunset; a nice massage at the end of the day. You don’t really enjoy a seven-mile run at six o’clock in the morning. You don’t enjoy getting punched in the mouth in sparring. That is just your life. It’s who you are, and I’m happy that’s what my life is because it brings so much fulfilment, respect, pride and love from people that don’t even know me; money; all these things come with the life I’ve chosen to live.’

At 36 years old, Eubank has won 35 professional fights, stopped or knocked out 25 opponents and has lost just three times. His father, who held both the WBO middleweight and super-middleweight titles between 1990 and 1995, is both iconic and enigmatic.

After a three-year period of estrangement, it looked like Chris Eubank Sr would be a notable absence from the fight with Benn. In what became one of the sensational storylines of the night, Sr arrived at the venue in the hours leading up to the match and walked with his son to the ring. It was a show-stealing moment and the pair remain in the midst of a reconciliation. Today, it’s not a topic he wants to dwell on.

Eubank Sr did not want his son to box, but Eubank Jr spent many of his formative years building resilience and character in boxing gyms in Las Vegas, Cuba and England. He was pitched in against contenders, champions and veterans and the lessons were hard. Now his life is one of celebrity, fame, eight-figure paydays and five-figure buy-ins.

Asked what he might miss most when he leaves boxing, he strokes the hair on his chin. ‘I guess I’ll miss the amazing shape you whip your body into. The week of the fight, you look in the mirror and it’s incredible to see the peak physical condition you’re in. Once you retire, you’ll never get to those levels again. You’ll never feel that superhuman again.

‘I’ll miss stepping into the ring and performing in front of millions of people, in front of the screaming crowd, that feeling of Michael Buffer calling your name out and getting your hand raised.’

Making the Weight

Making the Weight

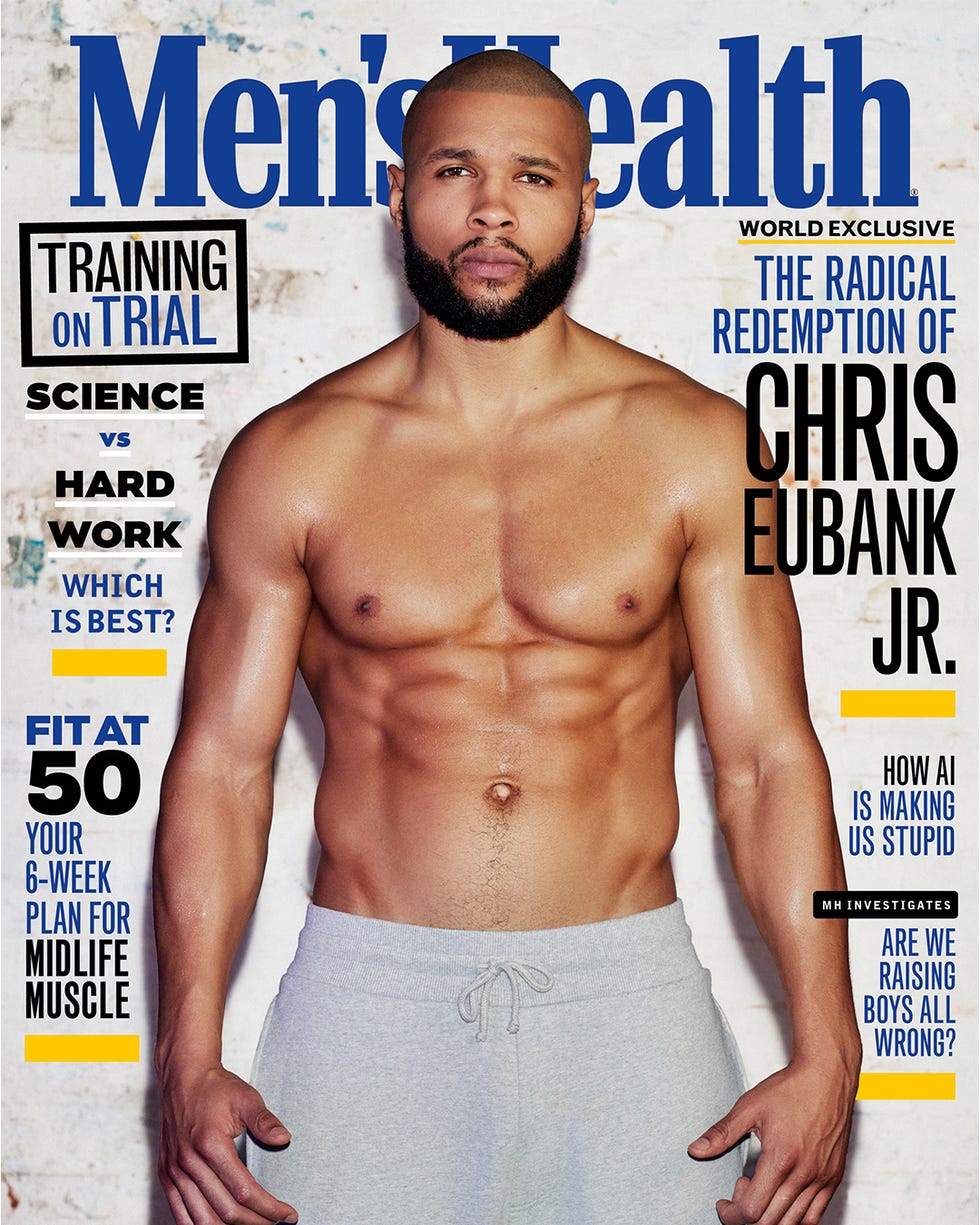

‘I like the sour ones,’ Eubank beams, helping himself to a sweet between shots for the Men’s Health cover, in an empty London warehouse two weeks on from our Zoom interview. He grazes on Percy Pigs and Haribos, but is happiest when he takes delivery of the Sour Patch Kids packet.

Eubank swigs from a bottle of water, his muscles looking sleek. He’s around 185lb and, when he fights, he tips the scales chiselled at 160lb. He is a few weeks from starting camp, so his post-fight indulgences of a Domino’s pizza and Krispy Kremes remain a way off. For now, the occasional sweet is as far as he can go.

When camp escalates and the discipline bites, pre-dawn runs will be followed by work in the gym throughout the morning and then sparring in the afternoon. It’s ironic that Eubank’s taut muscularity is one of the things he’s expecting to miss, for it was the torture of trying to make 160lb – and missing by just 0.05lb – for the first Benn fight that cost him £375,000 in a contractual forfeit.

The risks of Eubank ‘gambling’ by dropping weight for Benn, who was moving up, were also keenly debated.

‘You know what? Life is a gamble,’ he now admits. ‘Yes, there are elements of luck in poker, so in that sense you are gambling. You could say there are elements of luck in boxing. Sometimes it can just be a lucky punch; it can be one punch that can change the fight.

‘Some people would say you’re gambling with your health every time you step in the ring, and it’s true. Your health is at risk. But if you’re training, you’re dedicating your life, your mind, your spirit to a certain thing; to boxing.

‘Then, when you get into these rings and you make these weight cuts, then the “gamble” – as they like to say – the percentage of things you’re gambling with, it’s lowered. It becomes minute. It becomes a sure thing.’

How long Eubank will continue this high-stakes life is unsure. After Benn, he retains his ambition to fight the very best, and wants to leave a solid legacy.

‘I’ve made the bank, my friend,’ he grins, when asked about a money-spinning fight against the likes of Terence Crawford or Canelo Alvarez. ‘I could walk off into the sunset today and I’m set for life, so it’s not about bank any more. Now it’s about leaving behind a legacy I can be proud of.

‘It’s about, “How are you going to be remembered, and what are you going to be remembered for?” A fight like that is something that will leave a legacy that I could be proud of.

‘I’m already very proud of the things I’ve done, but that would enhance it. Sharing a ring with the best in the world, that’s an important thing to do, to test yourself. I’ve been testing myself my whole life and that might well be the next test after Conor Benn.’

But, right now, there is no focus on life after boxing, only an awareness that it might not be too far off. In preparation for such a time, Eubank has a role in the second season of Guy Ritchie’s The Gentlemen on Netflix, and speaks of acting with real joy.

‘It’s just an art form that I truly admire,’ he says. It was as a fan that Eubank first visited the set of the hit show to watch the cast filming. At one point, he turned to Ritchie and said, ‘I’d love to get involved. If you can squeeze me in anywhere, let me know.’ He was like, “I’ll think about it.”

A couple of weeks later he said, “All right, I’ve got somewhere I can put you.”’ Eubank likens the acting experience to a boxing press conference but with one significant difference: film allows him to further his pursuit of perfection.

‘The beautiful thing about acting is that there are many takes,’ he says. ‘There are many chances. You’ve got one shot in these press conferences. If you fuck up, if you say the wrong thing, if you stutter, you ruin the whole thing and you cannot go back.

‘In acting, you do take after take until it’s perfect and they edit. So, in that sense, the pressure is actually a lot more manageable.’

Living With Loss

Living With Loss

Eubank’s role in The Gentlemen is one he hopes he can build from, but the fighter, thoughtful and measured, says there’s no acting from him in real life. ‘I’m not a character. I’m a real person,’ he insists. ‘The things I do and say are real. It’s not for clout, it’s not for fame, it’s not for clicks. It’s just me; who I am.

‘I was very misunderstood at the beginning of my career because people didn’t know me,’ he continues. ‘I didn’t really say too much. I didn’t want to say anything. I didn’t want to talk to journalists or media – maybe I didn’t know how to – but I definitely didn’t want to.’

In time, he’s become more comfortable letting people in. That is never more apparent than when he talks movingly about losing his brother, Sebastian, who tragically died aged just 29 in 2021.

When asked about how he copes with the loss, Eubank presses his lips together, possibly thinking of closing the question down, but instead he confronts it. The pause is around 10 seconds. It feels longer, but the poker face never falters.

‘Going through something like that – the loss of a loved one, a close sibling – it changes your mind and your heart,’ he says, his chin positioned on his hand. ‘It’s either going to make you or break you. I chose to use this horrible situation to fuel my fire.

‘But it’s tough. And there are a lot of mental things you have to deal with – it’s either going to stop you in your tracks or push you to keep going, and to be strong.

‘It’s very important to have him in my mind and my thoughts whenever I’m going through tough times. Because he was a strong man; an inspirational man. We went through bad times and good times; he was my brother. I just try to live my life and do the things I’m doing the way he would want me to do them, and that gives me fulfilment and peace.’

Eubank wept his first tears in more than two decades when the grief hit. The tornado of sorrow swept through, leaving him calloused and hardened.

‘I cried for two days straight, and then I never cried again. Emotions, they just don’t have a place in my life’

‘The things I have to do, the person I have to be a lot of the time, if I think about things, it’s just not an option. And, if it was, I can’t do it. I’m just not built that way. Maybe that’s one of my downfalls. Maybe that’s one of my things I need to change, but I can’t change it.

‘A lot of people maybe need to touch their emotional side and be vulnerable – I’m not that guy. I never have been and I never will be. But that’s me. I’m a very different guy. I’m a very peculiar case when it comes to how a man should be, how a man should live his life.

‘I wouldn’t tell people to look at how I am and be that way. It only works in specific walks of life.’

There is no one in Eubank’s world with whom he confides his innermost thoughts. And he has not sought help. ‘These interviews are the only counselling,’ he says. ‘They’re the only therapy that I have ever had or will have. These are the only times I ever talk about anything when it comes to my emotions or my feelings, or whatever you want to say.

‘Outside of these interviews, I don’t talk about my feelings to anyone. Who am I going to talk to? I’m not gonna go to a therapist. I’m not gonna sit down with my boys and ask them for advice on how I should feel.

‘My old man was never built like that, to be emotionally involved like that. He was tough. He was strict. He was hard. There’s no one in my life that I have that type of thing with, or that I feel I need to have that type of thing with.

‘The things I deal with, I deal with them as a man. But what I make sure of is, I don’t keep revisiting the problems, you know? The hardships, the pain. I’ll talk about them every once in a while, but I don’t like to keep dwelling on it because it can bring you down.’

Though he refuses to dwell on it, Eubank won’t forget what has forged him into the man he has become. He now hopes that learning how he responded to tragedy might benefit others.

‘I know it helps people to hear about the things that people they look up to have gone through and how they overcome them. “If he can go through it, I can go through it and I can be strong, too.” I talk about them for other people; I don’t talk about them for myself,’ he says.

Eubank is a deeply complex and interesting man. As he looks through those stoic, expressionless eyes, one wonders about the pain, the love, the sacrifice, that has enabled him to emerge from the shadows of his father to become his own fighter, his own man.

Eubank Jr is now a household name in his own right, but he’ll be the first to tell you it’s taken time to win over the fans. And with 15 November on the horizon, there’s still further to go on this journey.

‘There are still people who hate me, think I’m an arsehole or a flash c*nt or whatever you want to call me,’ he says. ‘But there are a lot of people who understand I’m a genuine human being. I’m a good man.

‘It’s good to see that shift. I think the last fight was the first time I haven’t been booed into an arena in many years, maybe my whole career, so it’s interesting to experience a different dynamic.

‘It’s very rare that people’s minds change about someone, but that’s how it’s been with me.’

Chris wears: Jacket and shorts, both Stone Island; Shoes: Saucony X Silo; Watch: Audemars Piguet, Chris’s own

Additional photography: Getty Images

Grooming: Thembi Mkandla at Creatives Agency using Kiehl’s

This interview features in the November 2025 issue of Men’s Health – out now. Subscribe to MH by hitting this link.