Comparison between permanent and temporary ponds

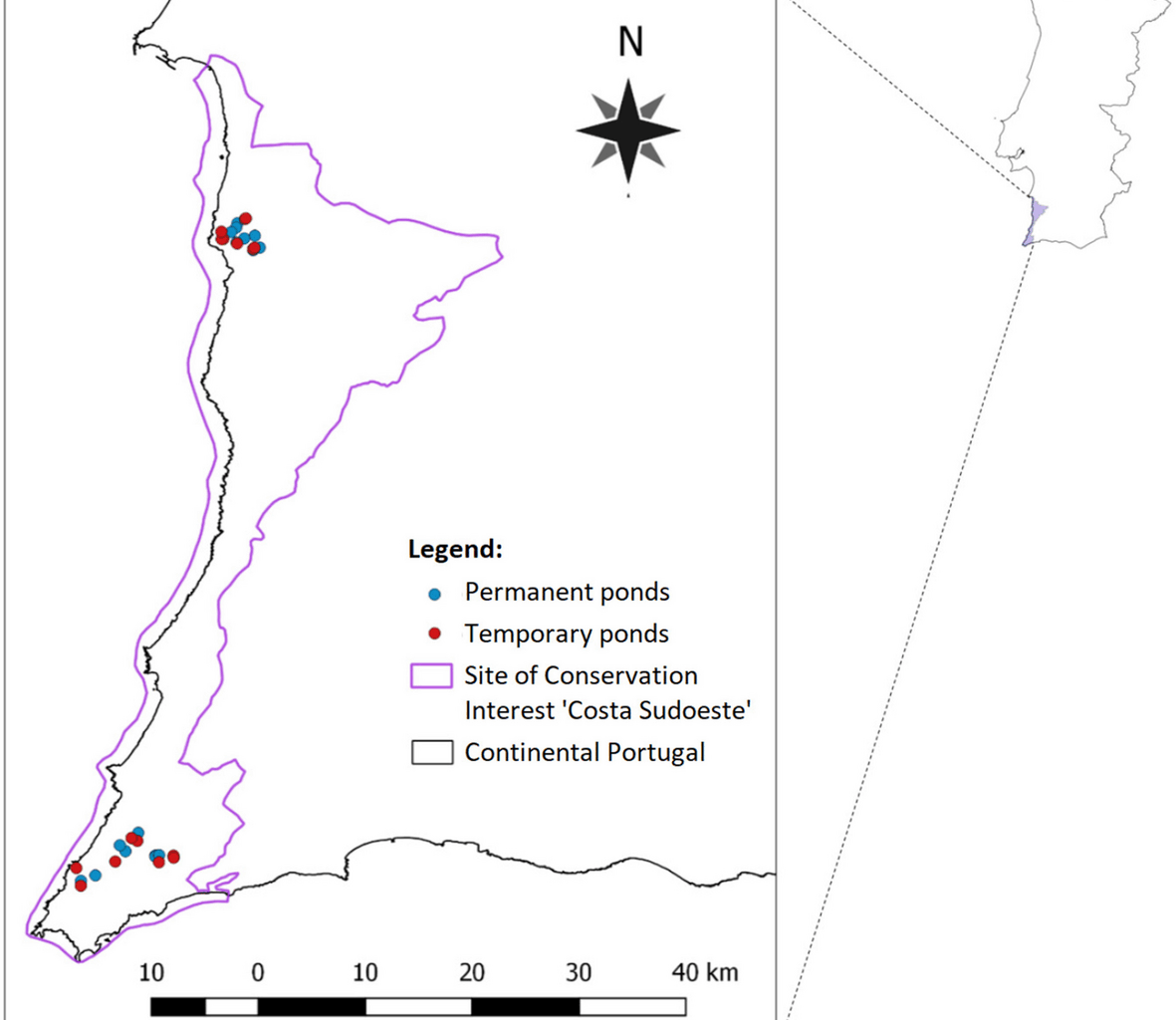

This study assesses the bat use of permanent vs temporary ponds by measuring bat overall and feeding activity, species richness, and considering biotic and abiotic features and surrounding land use type.

Permanent ponds supported significantly higher bat activity and richness species compared to temporary ponds. Furthermore, some common phonic groups/species (E. serotinus/E. isabellinus/N. leisleri and P. kuhlii) showed higher activity in permanent ponds, also with significant differences. In addition, M. myotis/M. blythii, M. escalerai and N. lasiopterus/N. noctula, which are phonic groups of high conservation concern [42], had greater activity or were only found in permanent ponds. These results indicate a clear preference of bats for permanent ponds, contrasting with Razgour et al. [54] and Williams and Dickman [71] who reported equivalent levels of bat activity and species richness in permanent and temporary ponds in drier regions. However, our results support previous inventories in the Southwest Portugal where very few species were recorded in temporary ponds: only P. kuhlii and E. serotinus [22]. While our study shows a great increase in the number of species detected in temporary ponds in the study area (a total of 12 species), species richness remains lower compared to permanent ponds.

Comparisons of pond features and surrounding land use revealed significant differences in pH, oxygen content, the proportion of temporary crops and biomass of Diptera, all of which were higher in permanent ponds. Although we did not measure water depth, the deeper water columns, observed in most cases in these ponds, likely contribute to the elevated pH and oxygen content levels [9]. The higher Diptera biomass in permanent ponds is consistent with other results comparing densities of Diptera in permanent and temporary ponds [9, 18]. In contrast, wind speed was significantly higher in temporary ponds, indicating greater exposure of these ponds, likely due to fewer surrounding trees and buildings that provide shelter. The more favorable conditions in permanent ponds, resulting from higher Diptera biomass and lower wind speed, may have contributed to the higher bat activity and species richness observed in these habitats compared to temporary ponds.

Effect of pond hydrological regime

Our findings from GLM models indicate that pond hydrological regime only influences species richness, leading to an increase in the number of species in permanent ponds. These results contrast with studies conducted in arid regions, where pond hydroperiod had no significant impact on bat activity or species richness. Razgour et al. [54] reported that pond hydroperiod only influenced bat community composition when associated with pond size, while Razgour et al. [55] observed that interspecific competition shaped bat communities and activity patterns, with species partitioning pond use either spatially or temporally.

However, in the Mediterranean region, the development of artificial wetlands has become a common management practice [21, 47], and bat species can indeed benefit from them [69]. New-built permanent ponds have the potential to increase opportunities for drinking and preying, reduce competition among individuals and increase connectivity between foraging habitats [29, 37, 65]. Amorim et al. [3] observed that bats showed weak associations with specific habitat features in spring during pregnancy, but, as the season advances, bat activity and species richness consistently increase on permanent waters over the breeding season. This suggests that bats may track spatial variations in water availability, particularly in regions like the Mediterranean, where temporary water sources decline from spring to summer [3, 24, 39, 69].

Although our study emphasizes the importance of permanent ponds, temporary ponds also remain highly valuable throughout the year. Salvarina et al. [60] showed that Mediterranean temporary ponds in Greece sustain high levels of bat activity and species richness year-round, influenced by distance from water, presence of water and air temperature. Together, these findings highlight the complementary role of permanent and temporary water bodies. While permanent ponds provide a stable habitat with consistent drinking water and insect populations, becoming crucial during critical periods of drought both for common and threatened species [3, 69], temporary ponds hold moist conditions that may be highly suitable for bats or their prey, even when dry, thus sustaining bat activity and diversity across seasons.

Effect of pond features and land use type

The increase in Diptera biomass and the surrounding proportion of urban areas, and the decrease in wind speed were the main factors influencing bats in our study. These variables were included in the models for overall bat activity, feeding activity, and species richness.

Diptera insects are the favorite prey for various bat species, including P. pipistrellus [6], P. kuhlii [25], P. pymaeus [7], N. leisleri, N. noctula and Myotis daubentonii [70]. Other species, such as E. serotinus and E. isabellinus, also consume substantial amounts of Diptera [35, 70]. Moreover, Rhinolophus ferrumequinum frequently preys on Diptera, representing about 35% of its diet [2]. Diptera are found in high densities in the permanent ponds [18] but are also abundant in temporary ponds [11], representing a dominant prey for bats. The arthropods biomass, which influenced bat overall and feeding activity, is directly associated with Diptera biomass. This influence is well-documented in the literature supporting the positive relationship between bats and the availability of arthropods [23, 30, 54]. The Arachnids biomass affected bat activity, as they are also consumed by insectivorous bats, although in smaller quantities (P. pipistrellus—[6],P. kuhlii—[25]). In addition, this importance is likely associated with the presence of Dipterans, as they are commonly preyed upon by Arachnids.

The proportion of urban areas is positively affecting the bat community likely due to the high availability of roosts in nearby buildings and other constructions. Roost-generalist species, such as Pipistrellus spp. and E. serotinus, thrive in urban areas and often roost in these environments, as they tolerate high light intensity and traffic noise [4, 52]. In particular, P. pipistrellus, the most common species observed in our study, is broadly described as an ‘urban adapter’ [27]. Our results are consistent with [44], who found greater species richness in urban areas and parks than in other habitat types, when excluding waterbodies. However, despite the overall increase in bat activity and species richness near urban areas, some species that are relatively common and urban-tolerant may still respond negatively to urbanization at a local scale [32]. In our study, Tadarida teniotis, Plecotus spp. and R. ferrumequinum were absent from ponds near urban areas, indicating that these species avoid or limit the use of urban settings in Mediterranean regions [40, 51]. While urban areas seem to support common species, improving shelter near ponds may attract rarer species and those of conservation concern. Thus, increasing tree cover or installing shelter boxes around the ponds should increase their overall value for bats, particularly for threatened species, provided the boxes are appropriately designed to minimize exposure to excessive heat and oriented towards the southeast. Further considering land use type, we also found that an increasing proportion of open forests, shrub and herbaceous vegetation surrounding the ponds negatively affect bat activity and feeding activity. In addition, the proportion of pasture had a negative but weak impact on feeding activity. While open forests with gaps between trees may sometimes benefit less maneuverable species [17], bats usually prefer to use ponds situated within dense tree cover, which enhances habitat suitability and shelter [27, 67]. Native and unimproved pastures seems to benefit bat communities, however, our pastures are intensively managed and there is no evidence of promoting feeding activity [31].

Furthermore, weather conditions had a significant impact on bats, despite our sampling has been restricted to nights with low wind speed (< 6 ms−1). This effect is commonly reported and may result from reduced prey activity and disturbances caused by ripples on the water surface, which interfere with the prey-target detection [17, 29, 58, 71].

This study contributes to an in-depth understanding of the importance of both permanent and temporary ponds for bat conservation in Mediterranean regions. Permanent ponds hosted higher bat activity and species richness, including more rare and high conservation concern species, which emphasize the ecological value of these habitats and the need to integrate them into bat conservation plans. Temporary ponds, despite being associated with lesser bat activity and a lower species richness, are still highly used by bats, which shows the important role they have in supporting local communities, even when dry [60]. In addition, they are an interesting ecosystem for several animal groups in the Mediterranean region, encompassing unique and endemic species [38].

Future research should focus on these ecosystems to explore potential variations in bat activity and species richness across different regions. Additionally, assessing the detailed vegetation structure surrounding the ponds, particularly along their edges, would provide valuable insights into habitat suitability for bats. A comprehensive approach that incorporates these factors could further inform conservation strategies and habitat management for bats in these environments.