At first glance, the photographs in “7 a.m. – 3 p.m.” seem to come from another lifetime: smoke curling over cluttered desks, towers of paper on the verge of collapsing, faces half-lit by fluorescent lamps. They belong to the 1990s, but they look older. They are like fragments from a dream about bureaucracy itself. The man behind the camera, Michalis Patsouras, wasn’t just a visitor, he was part of the system he was documenting.

These black-and-white images were once forgotten negatives in a drawer, but now, nearly 30 years later, they have returned as a photobook published by Hyper Hypo. The title, “7 a.m. – 3 p.m.,” refers to the Greek public sector’s working hours, but the book’s content opens a deeper inquiry into the nature of bureaucracy, the slow metabolism of institutions, and the way memory is elicited by objects and faces.

A quiet rebellion with a Leica

After finishing high school, Patsouras – the son of a military officer regularly transferred around Greece – found himself in Didymoteicho, a sleepy town near the Turkish border. His introduction to photography was accidental: a dusty darkroom kit discovered in a loft, a half-forgotten Olympus Pen EES-2, and a teenager looking for escape. “Once I started developing film,” he recalls, “I was fascinated. I decided I wanted to become a photographer.”

He moved to Athens to study at the Focus School of Photography, living in the downtown neighborhood of Petralona. Through a well-meaning uncle “who knew the ins and outs of the public sector,” he was offered a steady job. “He said: ‘Why don’t you work in the ministry? You’ll earn some money, pay for school, and you won’t have to work too hard.’ And that’s how I entered the public sector – completely by accident.”

The irony is clear: an aspiring artist inside the machine. But instead of rejecting the system, Patsouras turned his lens inward, photographing it from within. He found rhythm, melancholy, and quiet beauty.

An employee climbs the ministry staircase, carrying a stack of documents in a distinctly Kafkaesque scene. [Michalis Patsouras]

An employee climbs the ministry staircase, carrying a stack of documents in a distinctly Kafkaesque scene. [Michalis Patsouras]

His early years as a machine technician gave him access to every corner of the building – the Ministry of Commerce on Chalkokondyli Street, an interwar modernist structure designed by Munich-educated architect Emmanouil Kriezis. “I went from office to office, fixing typewriters, photocopiers, and fax machines,” he remembers. “When I finished, I’d take a picture.”

His camera was a Leica M6, loaded with Kodak Tri-X film and developed with HD-110 – a chemical developer once used by Ansel Adams. The combination gave his images a distinctive, grainy texture – “almost muddy,” he says – with the soft contrasts of fluorescent light. “If I had perfect grays and whites, it would have looked like something else. I wanted that atmosphere – the feeling of the fluorescent lamp.”

He sought to capture the rhythm of the day between 7 a.m. and 3 p.m. – the state’s working heartbeat – without any staging, use of flash or other artificial means.

The atmosphere of paper and smoke

There is something universal about this project as the ministry becomes a stage for modern life: the rituals of routine, the slow grind of systems, the dull choreography of people bound by paperwork. But it is also unmistakably Greek – that peculiar blend of absurdity, endurance and humor that animates everyday life.

The images range from the mundane to the surreal: piles of folders on dented metal shelves, employees smoking behind stacks of forms, a clerk ascending a Kafkaesque staircase with a stack of documents, a man pedaling a stationary bike in a basement, crowds spilling onto the street after a bomb scare (“bomb hoaxes somehow always happened after 12 p.m.,” Patsouras jokes, hinting at an inside job). Together they form a kind of bureaucratic fresco – an anatomy of public life amid the timid transition into the digital era.

“It was the height of Greek bureaucracy,” Patsouras says. “Everywhere you looked, people were carrying papers, pushing trolleys full of folders. In the corridors, cabinets overflowed with documents. In the basements, Dexion industrial shelves were packed with files bound with string.”

Visualization of the bureaucracy monster: rows of ministry folders – bound with string – filled with official documents. [Michalis Patsouras]

Visualization of the bureaucracy monster: rows of ministry folders – bound with string – filled with official documents. [Michalis Patsouras]

He insists his work was never meant as a denunciation. “It’s easy to judge – to say, look how bored they are. But it wasn’t their fault. Everyone does the same when there’s no motivation. It’s how the system works.”

Indeed, there’s a strange tenderness in these images: fatigue, yes, but also quiet humanity. The way a man leans over a desk; a clerk scratching his head as he cross-checks an endless roll of sticker labels; the small feast of pastries shared among colleagues.

For Patsouras, the challenge was both aesthetic and ethical. “Every time I lifted the camera, I knew I had only one shot,” he says. “We learned from Winogrand and Cartier-Bresson – don’t crop, get the frame right. That limitation made us better.” With time, he became invisible. “When people see you won’t give up what you are doing, when they stop noticing you, that’s when you capture the real moment.”

Life inside the machine

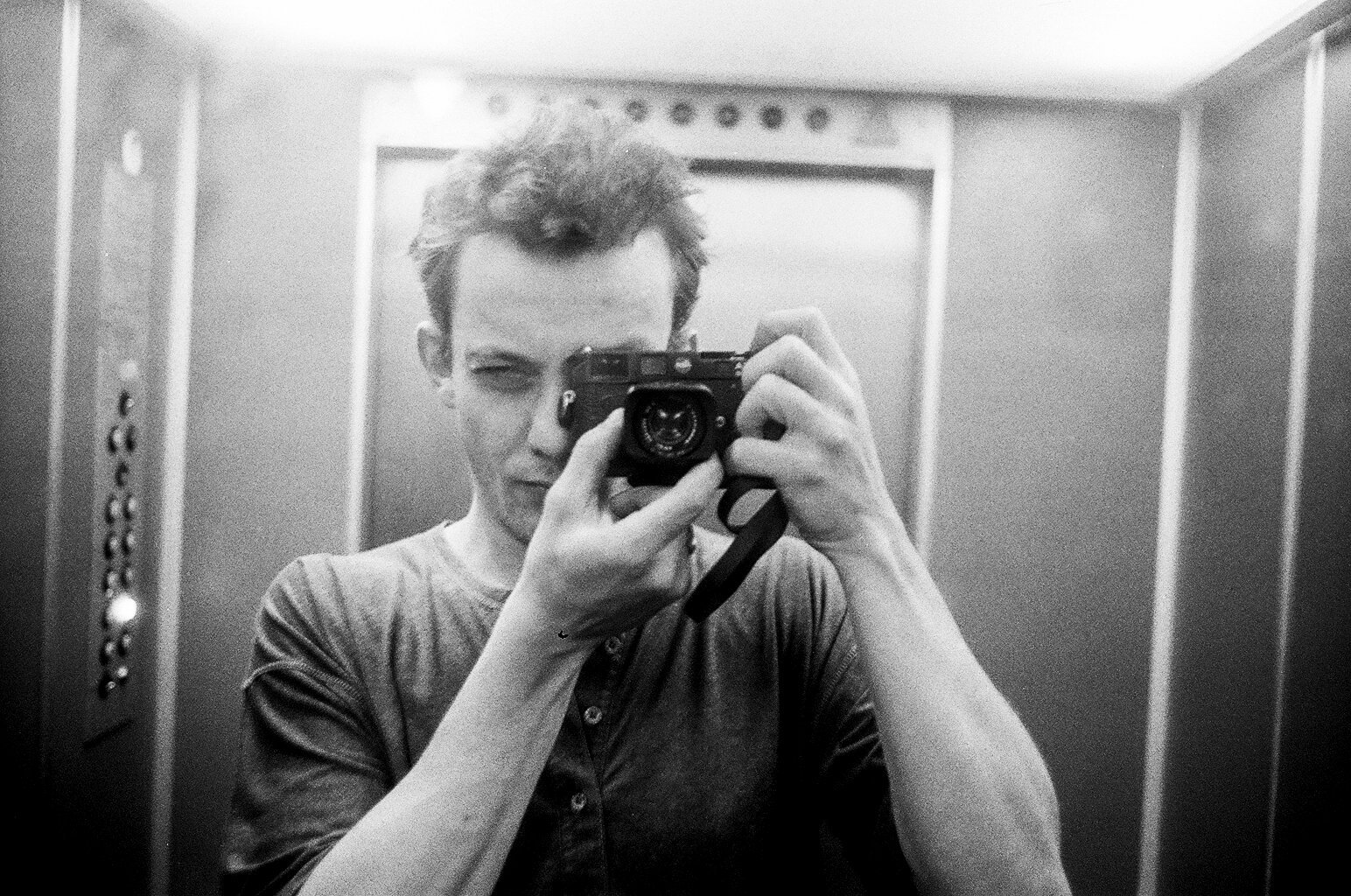

Among the images is a self-portrait: the photographer’s young reflection in the mirror of a ministry elevator, camera in hand. If “7 a.m. – 3 p.m.” has a narrative, it is the story of a young man realizing that the system he is documenting is also consuming him. After a few years, Patsouras was transferred from his roaming technical post to a desk job in the ministry’s procurement department. “That’s when I felt I would die there,” he admits. “As a technician, I could move everywhere. As an office clerk, I was confined. That’s when I decided to leave.”

He completed the project around 1998 – two years before resigning from the ministry. “I told myself, once it’s finished, I’ll go.” The negatives were stored away, quietly aging through the nation’s transformations: the millennium, the boom years, the financial crisis of the 2010s, the rise of digitization and the false promise of “Greece 2.0.”

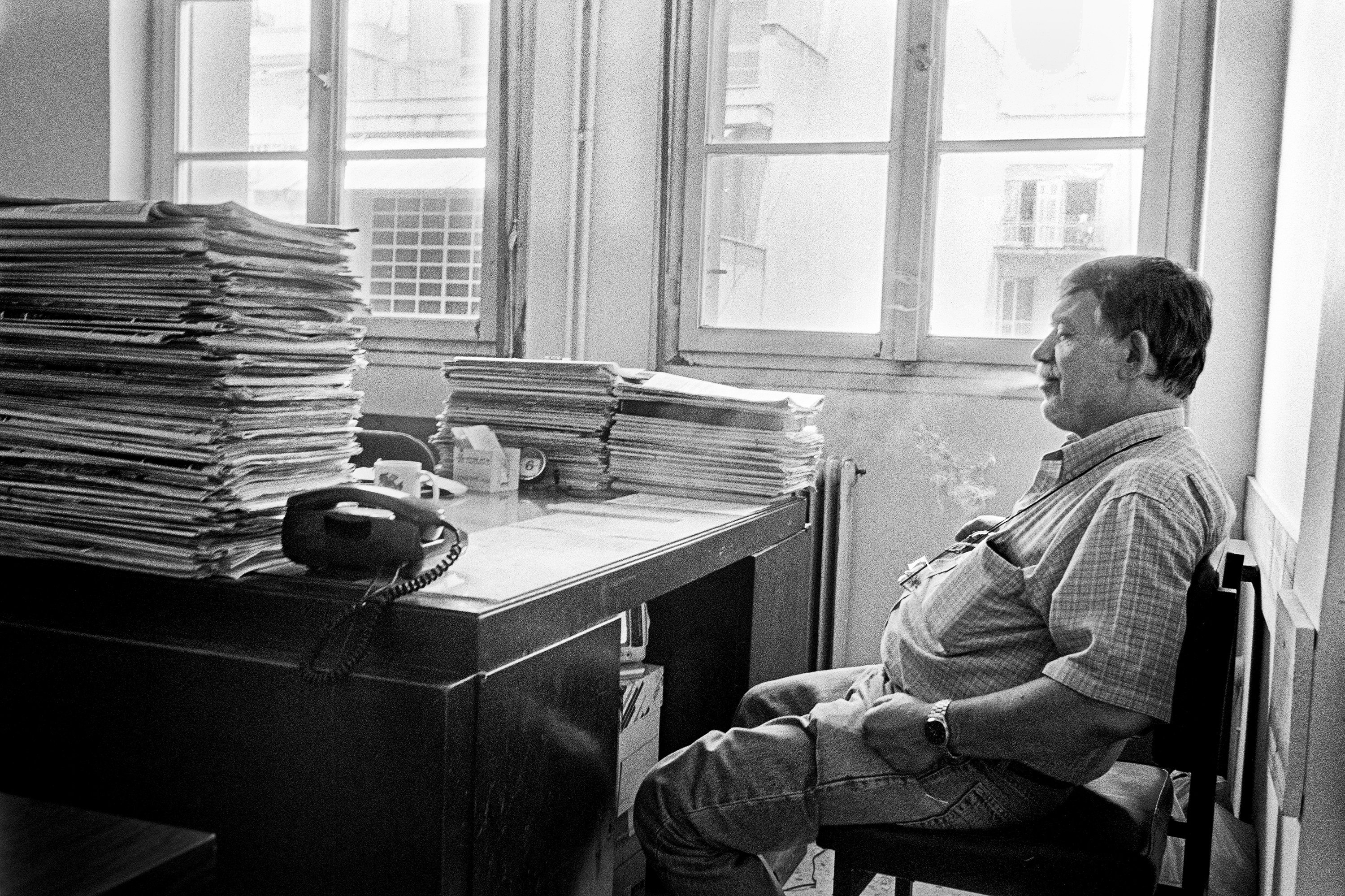

Slow day. An employee exhales cigarette smoke over a desk piled high with papers. [Michalis Patsouras]

Slow day. An employee exhales cigarette smoke over a desk piled high with papers. [Michalis Patsouras]

There is a sense of Greek tragedy in the characters, as they yield to their daily routines, seemingly oblivious to the changes looming ahead. Austerity measures, wage cuts, and administrative reforms swept through the analogue system – though never quite erasing it. The ministry that once employed 1,200 people now operates as the General Secretariat of Commerce, with barely 300 staff.

The photographs effectively function as both personal diary and collective archaeology – a record of a working culture that has largely evaporated, even as its structures persist. “At the time, I didn’t realize the value,” Patsouras says. “Years later, I understood: It wasn’t just my story. It was a historical document.”

From archive to book

The rediscovery came slowly. In 2022, he showed the series at the Photometria International Photography Festival in Ioannina, then at the Thessaloniki PhotoBiennale 2023, where curator Hercules Papaioannou of the MOMus Thessaloniki Museum of Photography recognized its significance and later wrote the accompanying essay for the publication. Exhibitions in Larissa and Athens followed, culminating in the Hyper Hypo photobook – a richly printed, nearly hundred-page hardcover in which the images speak for themselves, leaving only a faint longing for the backstage details captions might have provided.

Today, Patsouras continues to live and work in Athens as a professional photographer, focusing on long-term, human-centered projects. His work has received several awards and is part of the permanent collection of the Thessaloniki Museum of Photography.

A young Michalis Patsouras takes a self-portrait in the ministry elevator mirror. The project was completed around 1998 – two years before he left the job. [Michalis Patsouras]

A young Michalis Patsouras takes a self-portrait in the ministry elevator mirror. The project was completed around 1998 – two years before he left the job. [Michalis Patsouras]

The long dormancy of “7 a.m. – 3 p.m.” feels appropriate. It needed time – to age, to find its meaning in a changed world. Its slow maturity stands in contrast to the instant proliferation and self-presentation of today’s image culture, when everything is optimized and aestheticized. Patsouras remains unsentimental about both eras. “I’m not one of those who look back on the past with nostalgia,” he says. “It was a beautiful period of my life, full of creative exploration – but I’m not longing for it.”

Many of the people he photographed are gone; others, now gray-haired pensioners, appeared at the photobook launch a recent Wednesday evening at Hyper Hypo’s headquarters in central Athens. Their presence lent the evening a strange intimacy. It also confirmed that Patsouras’ camera, quiet and patient, was never regarded as an intruder. It entered the belly of the beast not to expose it, but to listen to its heartbeat.

7 a.m. – 3 p.m.

Photographs by Michalis Patsouras

Publisher: Hyper Hypo

Pages: 96

Material: Hardcover with obi band

Price: €42.00

The cover of the photobook, published by Hyper Hypo.

The cover of the photobook, published by Hyper Hypo.