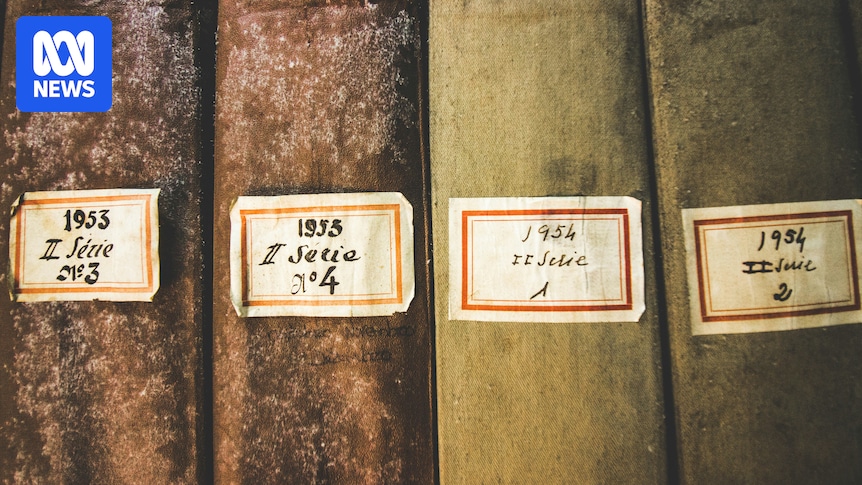

Letters, journals, private scribblings, saved memos, battered boxes bursting with faded photos and jaundiced newspaper clippings. This ephemera, alongside publicly archived material, is the beating heart of literary biography.

I have spent the past three years knee-deep in such treasures researching the life of Dame Quentin Bryce and as I uncovered golden nuggets revealing the inner thoughts and behind-the-scenes discussions of our first female governor-general, I started to wonder, “how will the next generation of biographers manage?”.

Letters and diaries are an especially vital source. A unique thought process is involved in constructing a letter, the pen gliding across the page as ideas, emotions and sometimes private confessions tumble out. The handwriting itself is an extension of its creator’s personality and state of mind.

“My biography of Queen Victoria would have been thinner and poorer without her immensely rich archive of letters and diaries,” says Julia Baird, author of the award-winning Victoria: The Queen, an insightful biography of the British sovereign. “It would certainly have been less true, more a groping in a fog than fixing an eye on the way she wrote, how often she wrote, the words she used, the words she crossed out, the words she underlined and wrote in italics, with great emphasis.

“I absolutely loved being able to read some of this material with my own eye too, in the archives, feeling the aged paper in my hands and watching her scrawl shift with the emotion she was feeling.”

Understanding these documents is an important part of biographical research, not just from what’s in them but from what’s left out. Literary detective work is painstaking but thrilling and involves a great deal of cross referencing, often scuttling down dead ends to uncover the truth.

“Much of the tale of discovery and research I did is about which diaries were burned, rewritten, obscured, and which letters were kept out of edited versions,” notes Baird. “Understanding this is important to understanding the way women have been misrepresented and misunderstood for centuries.”

Baird says much of Victoria’s passion was tempered by future editors and her mention of being a mother watered down.

“It is in the most candid of her correspondence, for example — her letters to her eldest daughter — that we discover that the tiny queen upheld as an icon of Victorian wife and motherhood in fact felt that any bride walking down the aisle was a lamb to the slaughter,” she says.

The biographer’s role is not just a matter of reading a person’s private or clandestine jottings but placing them in historical context. This is the stuff that can change history and what makes biographers hearts beat faster as they interpret the wider implications of this precious source material.

“Letters certainly play a critical role in how we understand history,” says Sophie Loy-Wilson, senior lecturer in Australian History at the University of Sydney. “So many important political ideas and social ideas about improving the human condition come from letter writing, people engaging with each other, famous correspondences.”

But here’s the thing. When did you last write or receive a letter?

Few of us write letters any more. (Alessio Fiorentino Unsplash)

An email just can’t compete

An email, text or emoji-filled social media message bears no comparison.

“Letters are often really productive in terms of seeing the ambiguities and the doubts that person might have had about their beliefs,” Loy-Wilson says. “Today we have lost this art form. I don’t even really write emails anymore. I send voice memos a lot of the time.”

Adding to this conundrum are questions about digital correspondence and records, not least whether they will even be accessible in future years with passwords lost and whole archives deleted to free up storage in the cloud.

Practicalities aside, can a biographer even trust virtual archives?

“This is very perplexing — the concrete documents of letters and various archives are so satisfying as they are, most usually, frank and unadulterated,” says Baird, who is concerned about potential for digital archives to be manipulated and changed by a host of interested parties, making fact checking extremely difficult.

“Will historians of the future need to have skills in coding, too? Will people be as careful about preserving electronic records, submitting to libraries for public scrutiny, as they were with boxes of notebooks and documents?” she muses. “It’s hard to know, but you can imagine passwords and other various blocking agents may provide considerable hurdles to various estates and families.”

(Penguin)

In the case of Dame Quentin Bryce, photos proved an intimate resource, reproduced in number throughout my book to amplify her story. Photos bear witness to so much — moments in time, expressions captured, relationships revealed, history recorded.

Of course we have these still, millions taken on smart phones every day. They mostly end up stored in the cloud, on phones, or in files on a computer. More assiduous record keepers may squirrel them away elsewhere, for safe keeping along with other important documents.

I certainly believed I had this storage lark licked with my series of external drives for the research and photos for all of my books over the past couple of decades, only to discover that either the drives themselves or the document formats are now incompatible with my state-of-the-art laptop. It doesn’t take long for storage methods to become obsolete.

(Harper Collins)

“I’m very aware of the old way and the new way, and I do love photo albums and photos,” says author and journalist Nikki Gemmell whose memoir of her mother, After, drew on vintage photos.

“I had so many photos from not only the 1950s when my mother was modelling in the Hunter Valley region in Newcastle, but also from the late ’30s and the ’40s.”

To record her own family’s history, Gemmell religiously makes up albums.

“In December every year I go back over the year’s photos, I print out several hundred and I actually put them in these blank books. I’ve had them since my first born, and I write little comments remembering the moment. It’s a record of our family through the last 24 or 25 years and it’s important,” she says.

Printing hard copies of photographs is rarely done these days. (Jon Tyson Unsplash)

Will AI write the biographies of the future?

One would hope public records are more able to keep up with the rigours of the digital world using up-to-date software and hardware to ensure nothing is lost and also to increase the accessibility of archive material. Loy-Wilson is sceptical.

“This transition to the digital world is the greatest kind of revolution in information and information technology, probably in human history, really,” she says. “And of course, it’s democratising. But this well of riches hides its curation so we are dependent on what’s available which involves oblique decisions, often budgetary decisions, made at various times by institutions currently under huge financial pressure, neglected by our political institutions… to their shame.”

Old-school manuscript collections like the National Library of Australia’s Patrick White Collection were very carefully preserved with fidelity to how the author or the producer of that collection imagined it to be preserved, she explains.

These days algorithms and AI influence what we see.

In digital archives our convenience is put in front of our intellectual integrity. Algorithms come into play to make choices for the biographer, and that is very problematic, Loy-Wilson believes.

And then we come to the troubled waters of AI’s model of scraping and mulching together material with scant regard for accurate sourcing. Award-winning British biographer Nigel Hamilton even suggests that the golden age of biography filled with rigorous research is likely to disintegrate as AI steps into the literary firmament and public funding for archives disappears with the end result of tomorrow’s biographies being written by AI.

“This is very likely to be the case,” sighs Baird. “I will always insist on reading books by humans. The entire enterprise of biography is, after all, about what it means to be human — deeply flawed but also capable of great things. All biographers must wrestle with each subject’s marbled soul — corrupted and noble motivations, moments of tenderness mixed with moments of selfishness, times of great courage with times of cowardice.”

Quentin Bryce: The Authorised Biography by Juliet Rieden, published by Penguin Random House.