There are, I think, some very interesting papers this time around.

Physicians vs AI: ECG edition

Shroyer S, Mehta S, Thukral N, Smiley K, Mercaldo N, Meyers HP, Smith SW. Accuracy of cath lab activation decisions for STEMI-equivalent and mimic ECGs: Physicians vs. AI (Queen of Hearts by PMcardio). Am J Emerg Med. 2025 Jul 30;97:193-199. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2025.07.061. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40763602

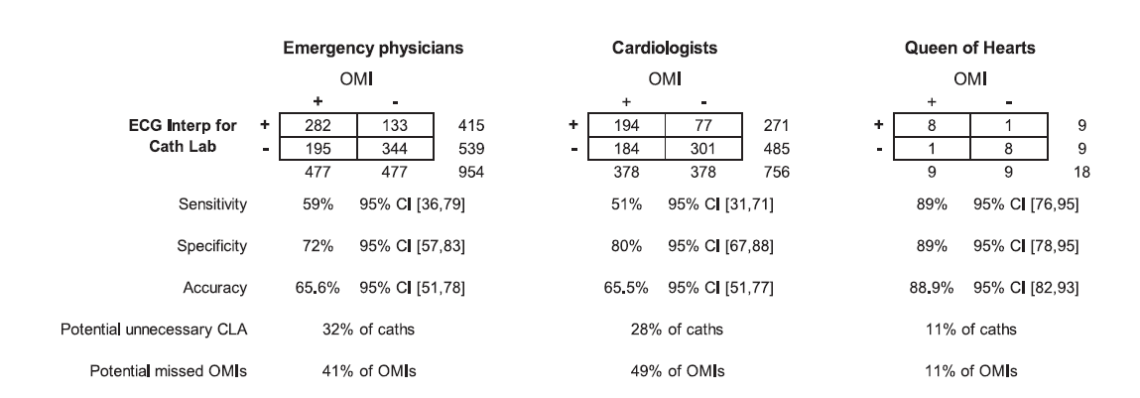

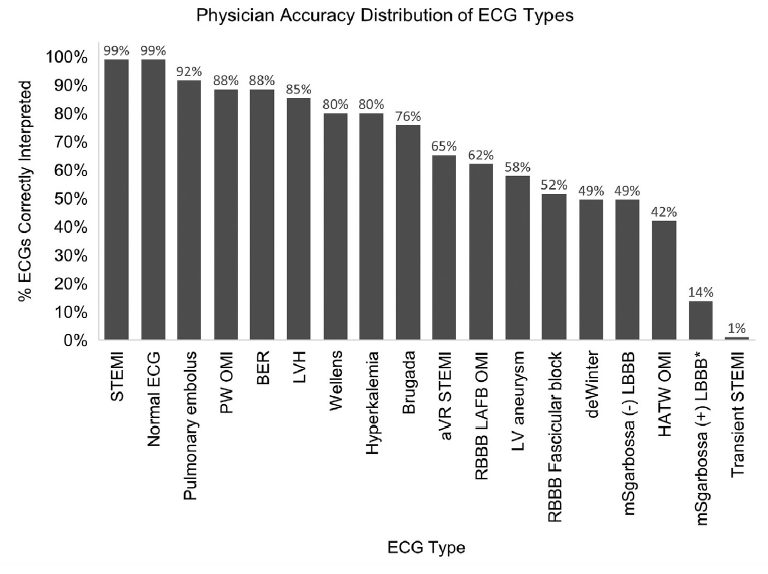

Everyone in emergency medicine should know Stephen Smith – his ECG website is absolutely essential reading. I have long used an app he developed to help assess subtle anterior ST elevation. Queen of Hearts is the AI tool developed by Stephen Smith (so conflict of interest alert for this paper) to try to improve the accuracy of STEMI interpretation in the emergency department. This is an online survey in which 53 emergency physicians and 49 cardiologists (with an absurdly high response rate) were shown hand selected ECGs of STEMI equivalents and STEMI mimics and compared to the AI model, with the binary outcome of whether or not cath lab should be activated. (I think this carefully curated group of ECGs might be a problem. There were no normal STEMIs, but humans are smart enough to judge a group of ECGs as whole, which may lead them towards decisions they wouldn’t actually make in real life. For example, if you show me 12 STEMI mimics in a row, I might decide you are trying to trick me, and call one or two STEMI, even if I would have called them mimics clinically.) Emergency physicians and cardiologists were equally accurate (66% vs 66%). This is an obvious outcome, but it is a blow to the stupid practice many hospitals have of requiring cardiology overreads of ED ECGs multiple days later when patient care is already complete. The AI model was significantly better than physicians, with an overall accuracy of 89%. Perhaps the most important thing to realize is that these numbers don’t mean anything. These are hand selected edge case ECGs. No emergency doctor is incorrect about 35% of STEMI cases. This data is just claiming that you might be incorrect about 35% of edge case ECGs, which would represent a tiny minority of overall ECGs. Of course, we don’t really care about overall accuracy; sensitivity here is more important than specificity. Unfortunately, the physicians’ sensitivity in this sample was pretty bad.

Of course, the gold standard matters, as does the phrasing of the question. Many of the ECGs that they describe as “requiring cath lab activation” would be thoroughly rejected by interventional cardiology at most hospitals (including my current hospital). If any of these physicians work at multiple sites, their answers may reflect that fact. If I was given many of these ECGs on a survey, I would have to say “no” to cath lab activation, because the appropriate answer is “consult interventional for high risk OMI”, but not immediate cath lab activation.

I think the biggest problem with the paper is the underlying ECG selection. One of the cases is “transient STEMI”, in which the participants were only shown a single ECG which does not have signs of STEMI on it, but apparently there was an EMS ECG that showed STEMI. Essentially every physician got this “wrong”, except that they didn’t get it wrong at all. The ECG displayed is not enough to activate a cath lab, which is the question the survey asked. Clinically, we would have all searched for the EMS ECG, or ordered repeat ECGs, and would have got to the correct diagnosis, but just with appropriate diligence. The other ECG that many physicians got “wrong” they admit was actually a mistake, and was a paced rhythm that was negative for Sgarbossa criteria. Blaming physicians for missing ECGs that don’t fit any guideline criteria for cath lab activation, and then praising an AI model for activating based on these ECGs, seems like a mistake. At very least, we would need to see how this AI model functions in the real world, with real clinical outcomes, rather than on a hand crafted survey, to suggest broad adoption. (Especially when the hand crafted survey was created by the owners of the AI algorithm. I don’t say that to be mean. Dr. Smith is one of the greatest emergency doctors in the planet, and has added more value to our specialty than almost anyone, but that doesn’t remove the inherent bias that can occur when conflicts of interest are at play.)

The ECGs are included in the supplemental material. They are not labelled, and so you can test yourself. I suggest doing so – it is probably a more worthwhile exercise than reading my rant about this paper. Perhaps it is because I have been reading Dr Smith’s ECG blog for more than a decade, but I found these ECGs very straight forward. I got 16/18 right, with a very high degree of certainty in my reads. In fact, the only 2 I got wrong were the two questionable ECGs mentioned above: “transient STEMI” case where the ECG displayed is actually not concerning and the other was a case where they state they accidentally used the wrong ECG where the rhythm is paced but it is actually Sgarbossa negative. Neither of these cases meet any normal criteria for STEMI or STEMI equivalents. When I look through these ECGs, the 66% success rate among physicians is somewhat concerning to me. It makes me think about airway studies where people have 80% first pass success rates – I am just not sure the results translate to high quality clinical practice. That makes me wonder about the added value of the AI tool. (Especially seeing as you can imagine that people who have not taken the time to master ECGs might be the same people who aren’t going to bother downloading an extra app to double check their ECG interpretations.)

Bottom line: In the long run, ECG interpretation seems like it will be an easy win for AI. I have even downloaded this app to try. However, especially when you consider the conflict of interest that needs to be considered, I don’t think this paper is enough to suggest that this AI program is necessarily better than physicians, nor that it should be used routinely in patient care.

You are reheating what?

Daniel NJ, Storn JM, Weinberg NE, Galvin WA, Irons HR, Barksdale AN, Rischall ML, Bilodeau SM, Gale JY, Willet KG, Wilson A, Keiper K, Chevalier J. Assessment of sous vide water baths in the acute rewarming of frostbitten extremities: A multicenter study. Acad Emerg Med. 2025 May;32(5):574-577. doi: 10.1111/acem.15061.PMID: 39654121

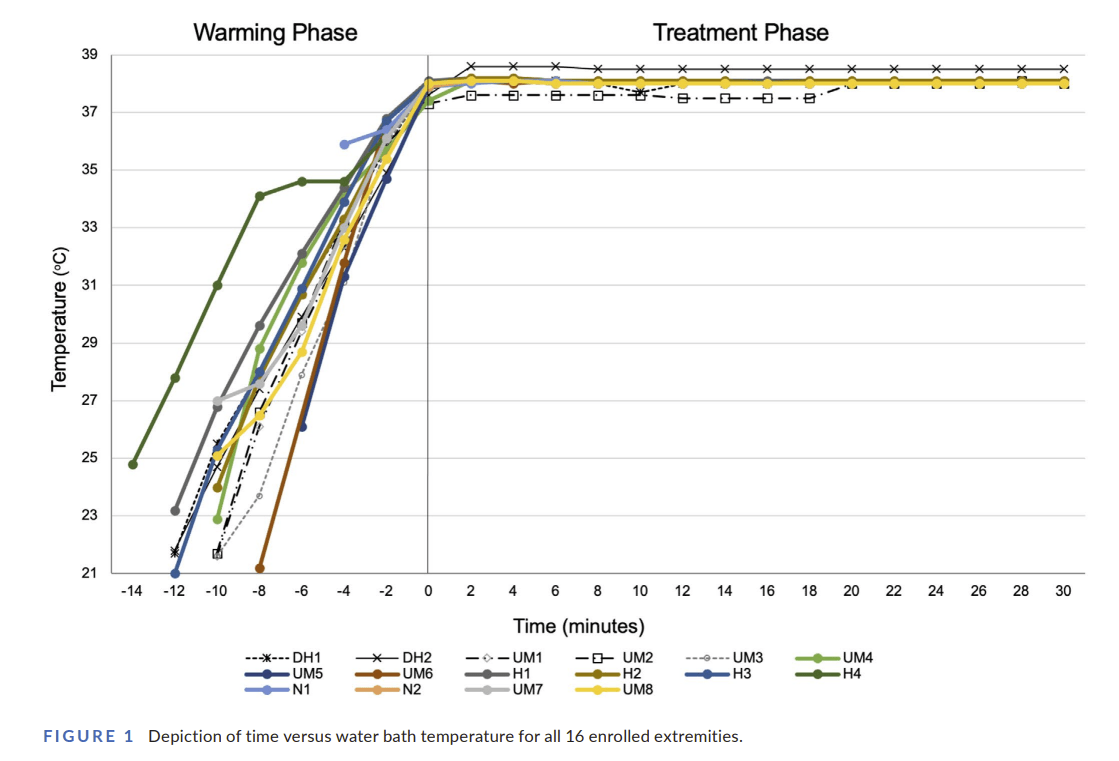

I am not sure how much value this paper will have, because, despite working in Canada, I almost never see cold exposure injuries. Therefore, I am not sure that stocking a specific device to manage frostbite will make sense for most departments. That being said, I was a very early adopter of direct to consumer sous vide devices decades ago, and I absolutely love the ingenuity of taking a cooking device specifically designed to hold a bath of water at a very precise temperature and using it for medical purposes. This is a prospective observational trial of 7 patients with 16 frostbitten limbs from 4 academic emergency departments, in which patients with frostbite had their limb placed in a waterbath at room temperature, and then a sous vide device set to 38 degrees Celsius was used to control the temperature of the water. The device was effective, getting the water bath to 38 degrees within 15 minutes and then very effective at keeping the temperature steady (which is the whole point of these devices).

All extremities were clinically thawed in one 30-min session. No adverse events were reported. In terms of ease of use, the sous vide method was rated a fairly easy (although the scale seems backwards to me), rating 2.8 out of 10 with 1 being the easiest. As compared to other methods, participants thought this was easier. Of course, there is no comparison group, no real clinical data, and all sorts of room for bias, so it’s not entirely clear what one is supposed to do with this paper. I wonder if people could come up with other uses for the sous vide device for the 99.9% of the time that you aren’t treating frostbite. One thing that comes to mind is keeping a stock of warmed IV fluids. We are always told that microwaves are dangerous, and apparently blanket warmers are also a no no, so perhaps this is a way to ensure you have a stock of crystalloid at a precisely controlled temperature. I guess the obvious use is to reheat your lunch, and I seeing as you sous vide in a plastic bag, you could even do that while managing the patient with frostbite.

As much as I love this paper, I am reminded of a paper I covered years ago that really highlighted the potential harms of “MacGyver” type interventions in emergency medicine, which is also worth a read: Duggan LV, Marshall SD, Scott J, Brindley PG, Grocott HP. The MacGyver bias and attraction of homemade devices in healthcare. Canadian journal of anaesthesia. 2019; PMID: 30980239

Bottom line: Sous vide devices relatively cheap, easy to use, and are good at controlling the temperature of a water bath. I like the ingenuity of using them in the medical setting, but I am very interested to hear other people’s opinions on this paper.

Your paracentesis method sucks

Konerman MA, Price J, Torres D, Li Z. Randomized, controlled pilot study comparing large-volume paracentesis using wall suction and traditional glass vacuum bottle methods. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2014 Sep;7(5):184-92. doi: 10.1177/1756283X14532704. PMID: 25177365

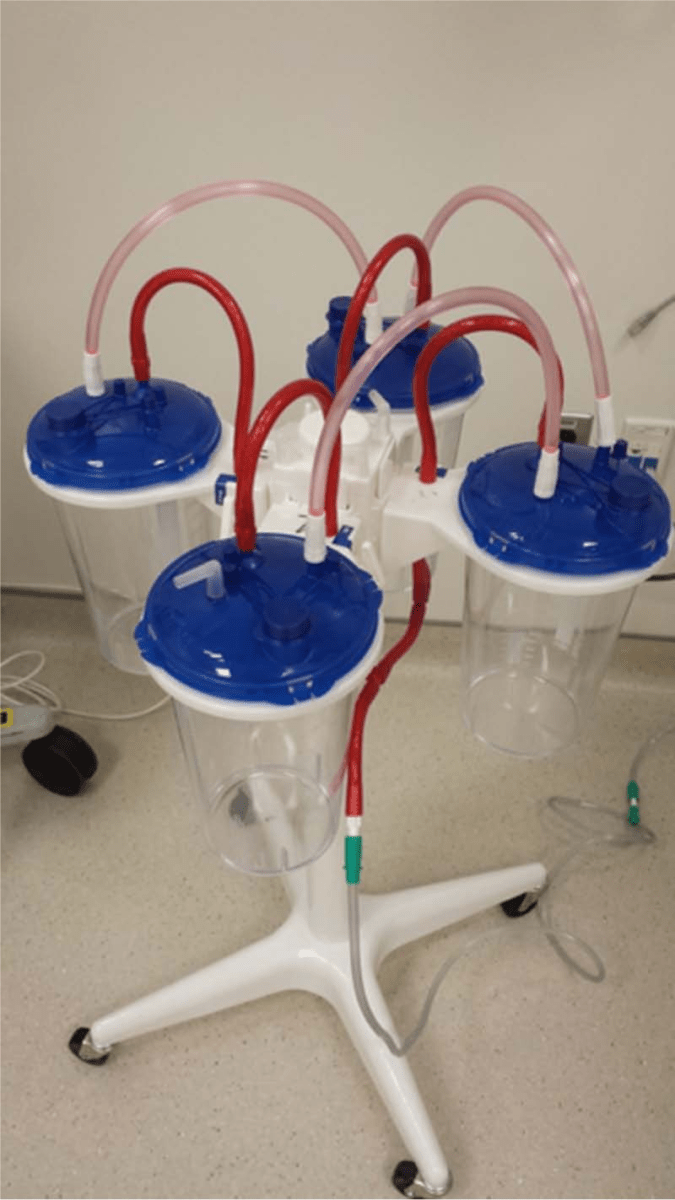

Paracentesis comes up a lot in emergency medicine, and if I am going to stick a needle in, I am going to try to get as much fluid off as I can to help the patient and try to avoid the risk of another procedure in the short term. Unfortunately, vacuum bottles are essentially always out of stock in the departments I work in. You can do this by gravity alone, but only if the patient has a ton of time, and you have a lot of patience for trouble shooting. Therefore, the concept of using wall suction to facilitate large volume paracentesis immediately caught my attention. This is a single centered RCT comparing wall suction to vacuum containers in 24 hospitalized adult patients requiring therapeutic paracentesis. For the wall suction technique, they connected multiple wall suction canisters in series, with the wall suction set at 200 mmHg. To connect this series to the paracentesis tubing, you either need a christmas tree adaptor, or you can just shove the suction tubing into a 5 mL syringe in a pinch.

The amount of fluid removed was 3 liters with individual vacuum containers as compared to 3.7 with wall suction. Despite removing more fluid, the wall suction was significantly faster (7 minutes vs 15 minutes), and when you count the hours I spend trying to track down these vacuum containers, there would be significant additional time savings for me. The wall suction canisters are also cheaper than the vacuum containers. All procedures were done by a single doctor, and this is a single center study, which might limit generalizability. However, it isn’t the procedural technique being studied, just the collection system, which should limit that concern. I have not had the opportunity to try this yet, but I think this small change could make a big difference for the feasibility of getting this procedure done in the emergency department. We could talk at length about the limitations of this small trial, but this honestly seems like stronger evidence than is necessary to make the kind of simple change they are describing.

Bottom line: If you are performing a therapeutic paracentesis in the emergency department, I think this wall suction technique seems like a very good idea.

It is somewhat important to know how the various ports on the suction containers work, so ensure you don’t end up suctioning fluid into the wall port, causing significant damage. This post from Maimonides goes into a little more detail.

Ok, maybe it is ticagrelor that sucks?

Kutcher SA, Dendukuri N, Dandona S, Nadeau L, Brophy JM. Ticagrelor Compared to Clopidogrel in Acute Coronary Syndromes trial (TC4): a Bayesian pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. CMAJ. 2025 Mar 30;197(12):E309-E318. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.241862. PMID: 40164463

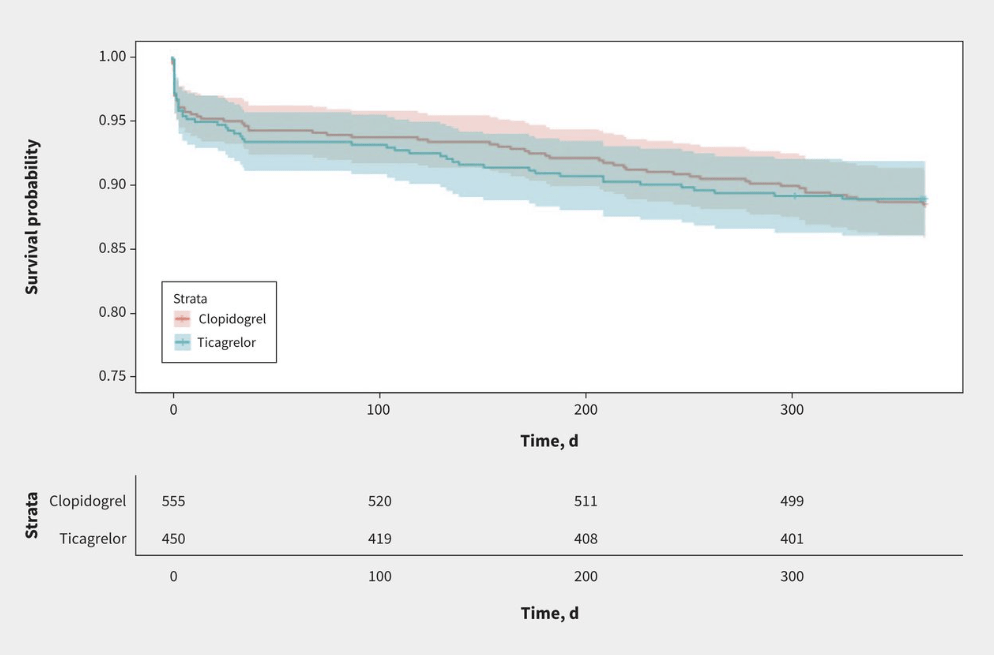

When it was introduced, with much fanfare and expensive industry sponsored dinners, I was skeptical of the benefits of ticagrelor. The cardiologists seemed to be overly taken by disease oriented outcomes looking at coronary flow during caths, but the clinical outcomes looked identical to clopidogrel. I have not really followed this data closely, because the cardiologists set our STEMI protocols, but there has apparently been a lot of controversy, including questions of scientific wrong doing. This is a single centre, pragmatic, open-label, time-clustered RCT comparing clopidogrel to ticagrelor in patients with acute coronary syndrome undergoing percutaneous coronary intervention. They used a composite MACE outcome (death, nonfatal MI, and ischemic stroke) as their primary outcome. This study uses a Bayesian analysis, which is a topic I will have to do a deep dive on at some point, because I think it has a very high risk of being misused, abused, and ultimately misleading us in medicine (despite being my preferred approach to statistics). However, this study does a good job basing their priors in published research, which is an important and often overlooked step. They enrolled 1005 patients, and it probably didn’t matter what statistical approach they used, because a 3rd grader can see the results were identical: MACE in 11% of both groups. Bleeding was also the same (5.0% vs 4.4%). There are clearly many limitations to a single center open label trial in which treatment was assigned by month, but given that there was never any good reason to adopt ticagrelor in the first place, I believe the results. Of course, for most of us, it doesn’t pay to dig too deeply into this data, because the choice is not made scientifically, but rather based on whatever the interventional cardiologist wants, which was mostly set by whichever drug rep paid for the fanciest dinner.

Bottom line: I never adopted ticagrelor into my practice, except when it was automatically included in a STEMI bundle. This paper won’t change anything. I will continue to use clopidogrel as my agent of choice, but don’t know that it is worth fighting if cardiology wants to waste money on ticagrelor in their STEMI bundles.

Trigger point injections: once a fad, now just bad?

Lajeunesse MD, Olivera TR, April MD, Benesch HA, Castaneda P, Couperus KS, Dang VN, Park MS, Deboer RS, Dougherty CA, Downing NC, Gray MW, Hull AM, Jimenez BL, Klausner MJ, Sakai JHM, McLean TJ, Nepal N, Patten HW, Schwartz BT, Walther ND, Wolterstorff CS, Oliver JJ. Trigger Point Injection for Myofascial Pain Syndrome of the Low Back: A Partially Blinded Three-Arm Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Emerg Med. 2025 Jun 17:S0196-0644(25)00298-7. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2025.05.008. PMID: 40531073

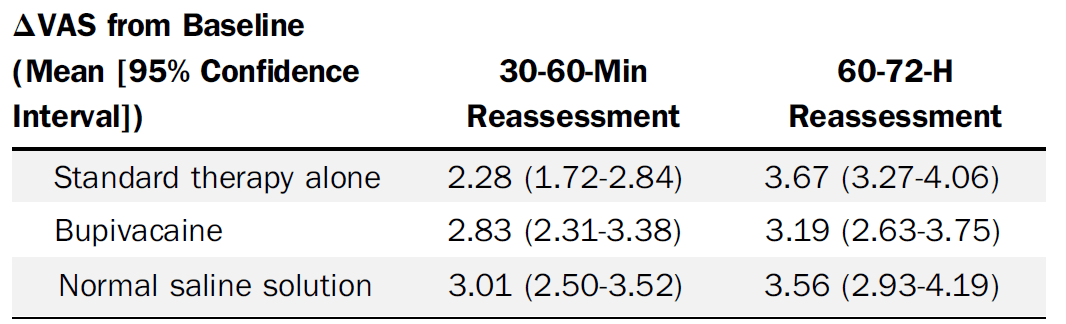

I am not sure if anyone out there is actually doing trigger point injections for back pain. They have been hyped at various times in my career, and I have even tried them, but nothing is all that effective for back pain, and my guess has always been that they are no more effective than acupuncture or any other placebo. That is basically what this RCT shows. All patients went home on ibuprofen, acetaminophen, cyclobenzaprine, and with instruction on heat and back exercises. It was a three arm trial: standard care in the ED (30 mg of intramuscular ketorolac and 975 mg of oral acetaminophen) versus standard care plus trigger point injections of 0.5% bupivacaine versus standard care plus saline injections. The saline versus bupivacaine groups were double blinded, but the standard care alone group was unblinded (they didn’t include sham injections). The quick summary is that the groups look identical in terms of pain reduction. I think it is a mistake to focus on short term pain reduction in chronic pain conditions, so the primary outcome of pain reduction at 30 and 60 minutes might be problematic, but they also have data at 60-72 hours that shows no difference. Obviously there are harms from needles, including bleeding (5%), increased pain (4-11%), and allergic reactions (0-2%). There could be some concerns about generalizability, as this was a primarily young male military population, but I see no intrinsic reason to think this would work any better in any other population. Overall, this is a well done study, and I believe the results: trigger point infections don’t seem to provide either short or long term relief in low back pain.

Bottom line: This is a well done placebo controlled RCT demonstrating no benefit from trigger point injections. The harms are probably minor, but harms clearly outweigh benefits here.

Anti-amyloid imaging related abnormalities: a nightmare for emergency medicine?

Rech MA, Carpenter CR, Aggarwal NT, Hwang U. Anti-Amyloid Therapies for Alzheimer’s Disease and Amyloid-Related Imaging Abnormalities: Implications for the Emergency Medicine Clinician. Ann Emerg Med. 2025 Jun;85(6):526-536. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2024.12.002. Epub 2025 Jan 17. PMID: 39818674

This is a relatively hot topic, so you have probably already heard about it, but if you haven’t, there are now potentially disease modifying anti-amyloid therapies for Alzheimer’s disease, and they seem to come with some significant complications that emergency physicians are going to need to know about. This is a good review if you haven’t heard of these therapies. The two agents currently approved in the US are lecanemab (Leqembi) and donanemab (Kisunla). Seeing as emergency doctors won’t be deciding whether to prescribe these agents, I won’t get into the question of whether they actually help, or whether benefit outweighs harm. What we need to know is that these agents are known to cause a relatively high risk (like 20-40%) of adverse neurologic events, including microhemorrhages and edema. These imaging abnormalities only show up on MRI, making our jobs very difficult in the ED. These adverse events are collectively referred to as “amyloid related imaging abnormalities”. Most of the time, this is an asymptomatic MRI finding, and so of questionable clinical relevance. However, there can be significant morbidity, and the presentations can be varied, including headache, dizziness, confusion, gait-disturbance, and seizures. These presentations will be complicated by difficult histories and physicals, given the population these agents are prescribed to. Given that these medications are biweekly or monthly infusions, they might not make it onto a patient’s medication list, and dementia patients are not always able to reliably tell us what medications they are on. Furthermore, given that most of these patients are asymptomatic, MRI findings in a symptomatic patient could easily be false positives, and so it will be important to keep a broad differential diagnosis to avoid missing things like encephalitis or meningitis in a higher risk (geriatric) population who classically have atypical presentations. Even when asymptomatic, these patients may have a higher risk of intracranial hemorrhage, and so we will have to be vigilant when prescribing anticoagulation for things like atrial fibrillation and PE. (Perhaps these patients will even need to wait for a screening MRI before anticoagulation can be prescribed?) The topic I hear discussed most is the potential risk with thrombolytic therapies in stroke, but that might be an American bias, because dementia and poor baseline function is probably a reasonable exclusion criteria for aggressive stroke therapies. These agents seem to represent a myriad of problems for emergency medicine, without any established diagnostic or therapeutic algorithms. That being said, information is still very limited, and most of these ‘adverse events’ are self resolving asymptomatic MRI findings, so despite the fact that cerebral edema and hemorrhage sound concerning, this could turn out to be a lot of nothing.

Bottom line: If these agents actually alter the course of Alzheimer’s, they will clearly be a godsend for an awful condition. However, for the time being, there are a huge number of questions, and the complications of these agents look like they could represent a nightmare for emergency physicians.

Look me in the face and tell me that I needed to be transferred

Castillo Diaz F, Anand T, Khurshid MH, Kunac A, Al Ma’ani M, Colosimo C, Hejazi O, Ditillo M, Magnotti LJ, Joseph B. Look me in the face and tell me that I needed to be transferred: Defining the criteria for transferring patients with isolated facial injuries. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2025 May 9. doi: 10.1097/TA.0000000000004651. Epub ahead of print. PMID: 40341445

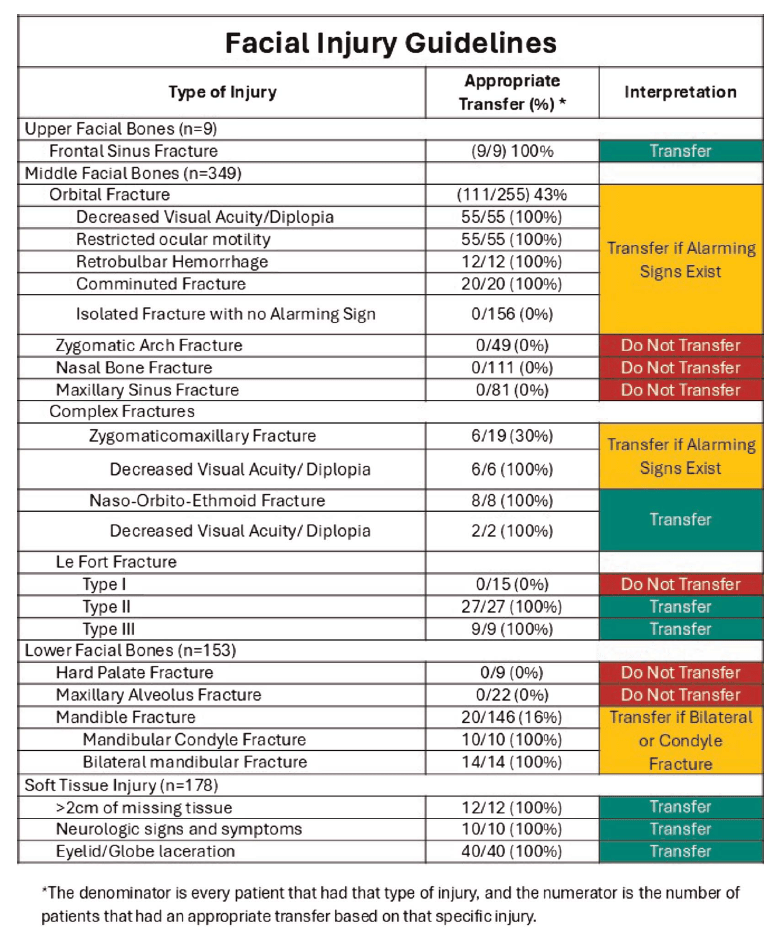

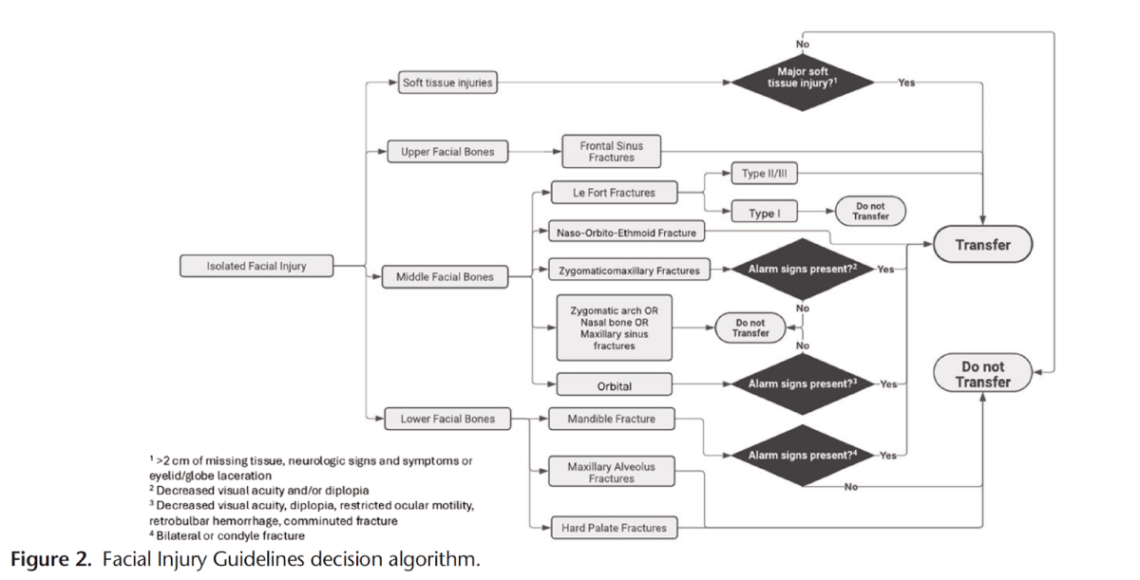

I have previously covered the brain injury guidelines, and discussed their potential to spare us unnecessary phone calls to neurosurgery. I am a big fan of that effort. Now, we have the face injury guidelines, although I am not sure I see the same overall value. (When discussed on EMCrit, they made it seem like patients were being transferred to trauma centres all the time for isolated facial injuries. Perhaps that is just an American thing, because I can’t remember a single time in my career when I had to transfer a patient for an isolated facial injury, which sort of undermines the value of this effort.) This paper (with an excellent title) is a chart review attempting to identify patients who did not require admission or urgent intervention, and who therefore did not require transfer or same day consultation. They identify 511 adult patients over a 5 year period who were transferred to their single center level 1 trauma center for isolated facial trauma. They defined transfers that did not require immediate operations, interventions during the initial admission, or admission for observation as “inappropriate”. (Unfortunately, such a definition assumes a system that has adequate outpatient follow-up without the initial transfer. It is all well and good to say I don’t need to consult you on day one, but if all the patients I send get appropriate outpatient appointments, and the patients I don’t send get lost in the system, the consult is still completely necessary.) Based on these criteria, they determine that 51% of the transfers were ‘inappropriate’, although only 39% were discharged home from the emergency department, so there seems to be a bit of a gap in their numbers. Of the ‘inappropriate’ transfers, 10% did require outpatient surgery, which makes the transfer or consultation at least somewhat appropriate (although in a functional system, this could clearly be arranged over the phone without physically moving the patient.) Based on their findings, they come up with some recommendations about which patients should be transferred. Given the severe limitations of a single center chart review, I would take these recommendations with a massive grain of salt. Furthermore, I am not sure “transfer” is the appropriate verbage, because even though these are traumatic injuries, I think these would be managed by local plastic surgeons in community hospitals in many health systems, and so we need to be careful not to misinterpret American specific healthcare idiosyncrasies. That being said, if I replace “transfer” with “same day consult”, these recommendations make sense, and I think basically state exactly what almost all of us are already doing (except apparently in this American healthcare system).

Sulingual epi??

Kraus CN, Wargacki S, Golden D, Lieberman J, Greenhawt M, Camargo CA Jr. Integrated phase I pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of epinephrine administered through sublingual film, autoinjector, or manual injection. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2025 May;134(5):580-586. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2025.01.006. Epub 2025 Jan 16. PMID: 39826899

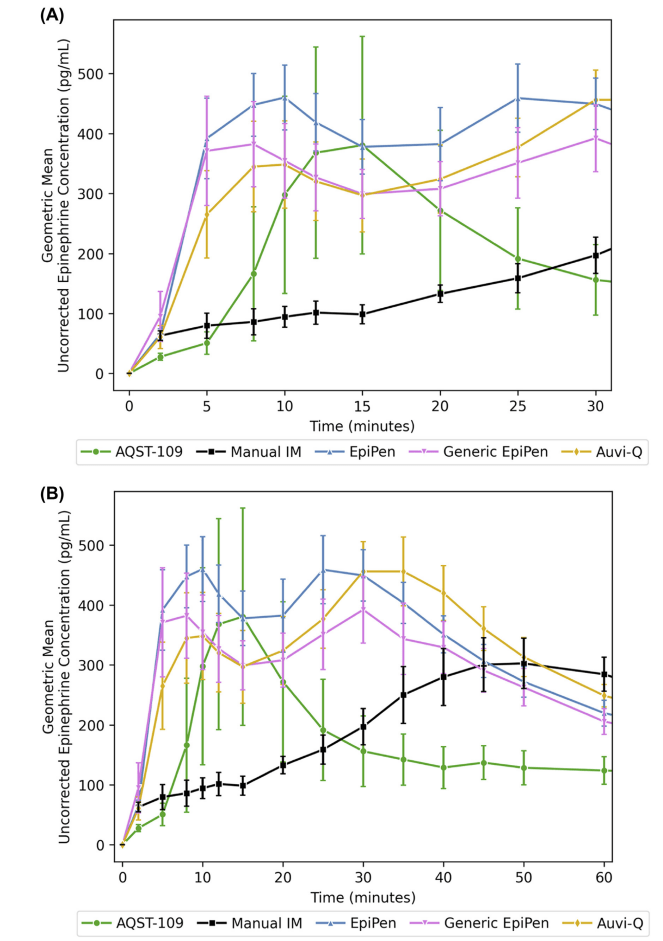

Epinephrine autoinjectors are very effective devices (although we did recently cover a review questioning their clinical outcomes). However, they can only help if they are used, and a significant percentage of anaphylactic patients arrive at the emergency department without having self-administered their epinephrine. There are many reasons, but fear of needles is definitely one. Another is the inconvenience of carrying the bulky auto-injector with you at all times. This paper discusses a novel mechanism for epinephrine self-administration which might get around those issues. AQST-109 is a sublingual film that delivers a prodrug of epinephrine, and this paper describes 2 phase 1 trials comparing the pharmacokinetics of AQST-109 12mg sublingual to manual injection of epinephrine 0.3mg IM, an EpiPen, a generic EpiPen autoinjector, and a fancier auto-injector (Auvi-Q) that talks, in healthy volunteers. (There is no clinical data, and so if you are only looking for practice changing papers, you can stop reading.) They measured plasma concentrations of epinephrine at 5 minute intervals, and present a lot of numbers, which may or may not end up being clinically relevant, and are hard to rapidly summarize here. To my eye, AQST-109 might be good enough, but is definitely a little slower, has a slightly lower peak, and lasts a little less long than the auto-injectors, although all are well above the 100 pg/mL that is apparently the threshold the FDA considers effective. The most surprising part of this data, to me, is that manual injection of epinephrine results in much lower plasma concentrations throughout the first 30 minutes. (Perhaps this is why we have all moved to using 0.5 mg when given manually in the hospital.) Another surprise is that ASQT-109 had bigger increases in heart rate and blood pressure than the other options in the first 10 minutes, despite having lower serum concentrations. I would have expected, if anything, the opposite result, especially when you account for the physiologic response to a needle. I can’t tell from this paper if the prodrug might also be biologically active in some way? These are healthy volunteers, and so it is possible that the sublingual approach might be significantly worse in anaphylaxis, if for example angioedema impaired absorption. Obviously, non-clinical data from the company trying to sell what will almost certainly be an expensive new drug should also be looked at very skeptically. However, if this sublingual approach really gets approximately equal drug concentrations to auto-injectors, it seems like this is something we will probably see in the future.

Bottom line: We won’t see this clinically for some time, but I am sure our patients would appreciate a sublingual treatment for anaphylaxis if this pans out.

Cheesy joke of the month – Halloween edition

Why didn’t the skeleton cross the road?

He didn’t have the guts

Like this:

Like Loading…