New research from the University of Newcastle has revealed PFAS levels matching those found in the Williamtown contamination zone could significantly alter male reproductive health in animals.

The pre-clinical study exposed subjects to PFAS-contaminated water at concentrations reflecting real-world environmental exposure in the Williamtown area of New South Wales.

The study highlights a potential new mechanism of harm: PFAS may not directly damage male reproductive health, but instead alter the molecular signals sperm carry – crucial for healthy embryo development.

“This is the first time we’ve shown that PFAS exposure at environmentally relevant levels, equivalent to those detected in Williamtown, can change the molecular makeup of sperm with potential implications for disrupting embryo development,” explained Professor Brett Nixon, who co-led the study.

Impacts of PFAS on reproductive health

PFAS are synthetic chemicals that persist in the environment and accumulate in living organisms. Mounting evidence suggests they may pose risks to human health, including impacts on male fertility.

The latest findings in animals raise concerns about the potential long-term and generational effects of PFAS exposure.

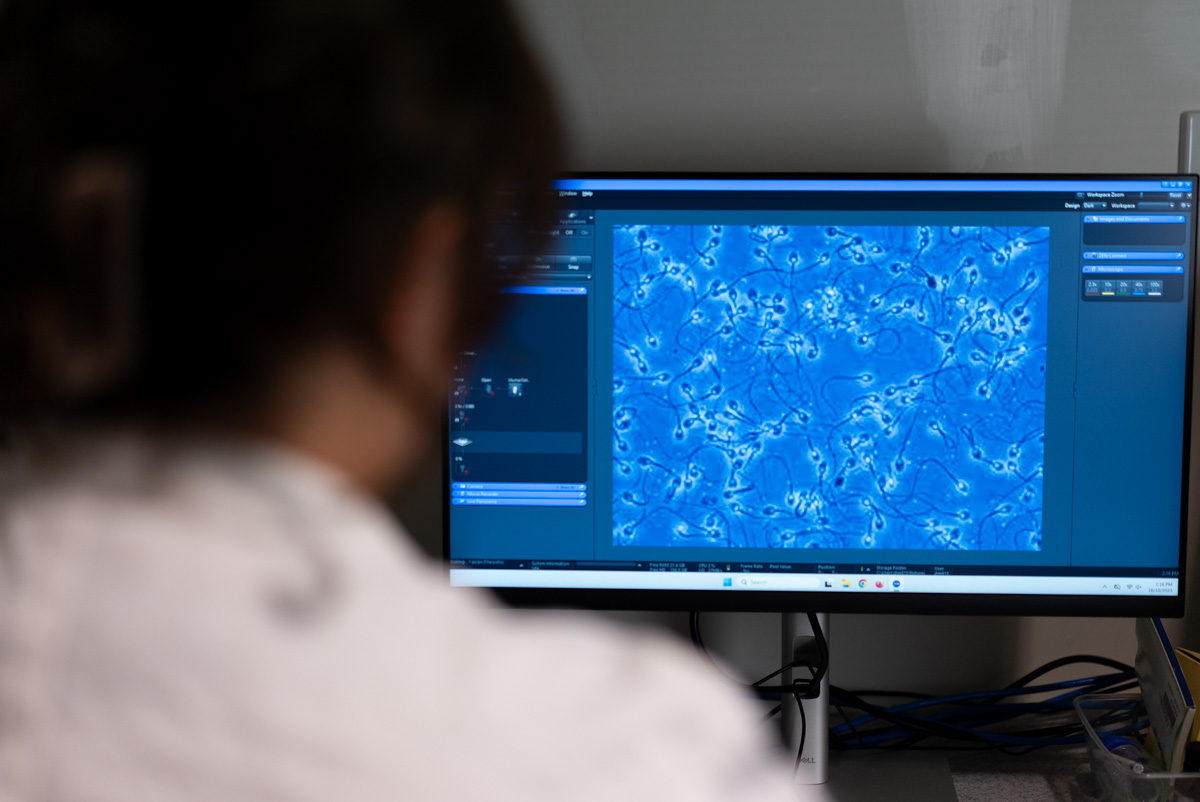

The findings are based on pre-clinical studies on mice and reveal:

Developing sperm count dropped: Day-to-day sperm production decreased during the PFAS exposure period.

Male hormone levels fell: Testosterone and DHT (dihydrotestosterone; a potent androgen hormone derived from testosterone), which are vital for sperm production, were reduced.

Sperm carried hidden changes: Molecules that help regulate gene expression were altered.

Embryo development was disrupted: Early embryos showed abnormal gene expression.

Sperm still functioned normally: They could move, survive, and fertilise eggs in lab conditions, despite the molecular changes.

These findings echo human studies showing lower sperm counts in men with high PFAS exposure and suggest that paternal PFAS exposure alone could have consequences for children, even if the children themselves are not directly exposed.

Dr Jacinta Martin, the study’s other co-leader, stated: “One of the predicted changes we noticed was related to body size – and the potential for offspring fathered by PFAS-exposed animals to be born, or grow, significantly larger than normal.”

Drinking water is a main source of PFAS exposure

The study was based on a real-world environmental exposure and emulated the levels and types of PFAS found in samples from a groundwater monitoring well located in the Williamtown contamination zone.

Furthermore, the subjects in our study were exposed to PFAS via contaminated water consumed over a 12-week period.

More research into the link between PFAS and reproductive health is needed

The research project is an example of the University of Newcastle’s commitment to helping its communities live better, healthier lives.

Further research and funding are needed to understand how PFAS exposure affects offspring health, and how combined maternal and paternal exposure may interact.

The community is now invited to attend a public forum on male infertility with experts in reproductive science and IVF. Hosted at NEX Newcastle on 30 October from 6pm to 8pm, the public can register for the free event here.