Our analysis demonstrated discrete strategies for approaching patient emotions in clinical settings. Surgeons described both conscious, deliberate and unconscious responses to patient emotions. When describing others, interviewees recognised that some strategies are more helpful for the patient, and in self-reflection, some could see benefits and issues with their own approach. Surgeons’ techniques could be universal, or they could employ different approaches, depending on the situation.

Conscious and unconscious approaches to empathyEmpathy threshold

If a clinical situation had parallels with the surgeon’s own life, then the emotional response was more likely to be spontaneous and have a stronger impact on the surgeon. One interviewee called this the “empathy threshold”. It was affected by previous patient interactions, one’s own life experiences, and other personal biases. This led to easier emotional engagement with some patients than with others.

[W]e bring a threshold into that interaction with us… The most obvious example is … someone with a cancer diagnosis. I think society and med school and the whole thing has geared us towards that being a low threshold for developing empathy… Whereas if it was someone with something more stigmatised – mental health, addiction, obesity, … There is a threshold that needs to be overcome. – A04.

Empathy as an optional tool

Participants talked about a deliberate choice to turn empathy on and off. The choice was often made around utility or efficiency. That is, surgeons could use time and energy to engage with emotions if it made a difference in the outcome or consultation.

The idea that surgeons lack empathy I think is a different one to surgeons don’t display empathy, don’t use empathy or however that should be worded. But I wonder if that’s what it is, whether empathy is something we see as a tool to use or not use depending on the situation in front of us. – A04.

This idea demonstrated that different aspects of surgical practice needed different attention to emotion. Surgeons used concrete methods, such as adjusting scheduling to facilitate or inhibit emotional discussions. Surgeons described predicting the degree of emotional stress in an upcoming consultation and deliberately increasing or reducing allocated time or arranging psychological support. This could also be used to reduce emotional engagement.

If it’s … a situation that …, may be quite distressing for you as the surgeon… You might want to avoid going and unpacking and moving them from a patient to a person, or a condition to a person because of the costs associated with that…. So, your choice of how much you choose to engage with that patient will then influence …the depth and the richness of the empathy that actually is developed. – G08.

Strategies to deal with emotions

To describe the approaches of surgeons to emotions, diagnosis and treatment can be considered to have a biological component (illness) and an emotional component (emotional dysfunction), which vary in strength, depending on the pathology and patient. Strategies ranged from directly addressing patients’ emotions to completely avoiding them. “Emotion-facing strategies” diffused emotions in some way, and “Emotion-avoidant strategies” bypassed emotions and focussed primarily on the biological illness. This could encompass other factors of treatment like psychological, social, and other stressors, via their impact on emotions.

Surgeons described different approaches to emotions depending on context and condition, but also on the personality and comfort level of the surgeon. For example, the interviewees felt that the emotion-facing strategies were easier in clinic consultations and that the emotion-deferred or emotion-avoidant strategies were more likely to be used in emergency or ward settings. However, many described feeling most comfortable with one particular strategy, even if they understood its limitations.

Emotion-facing strategies

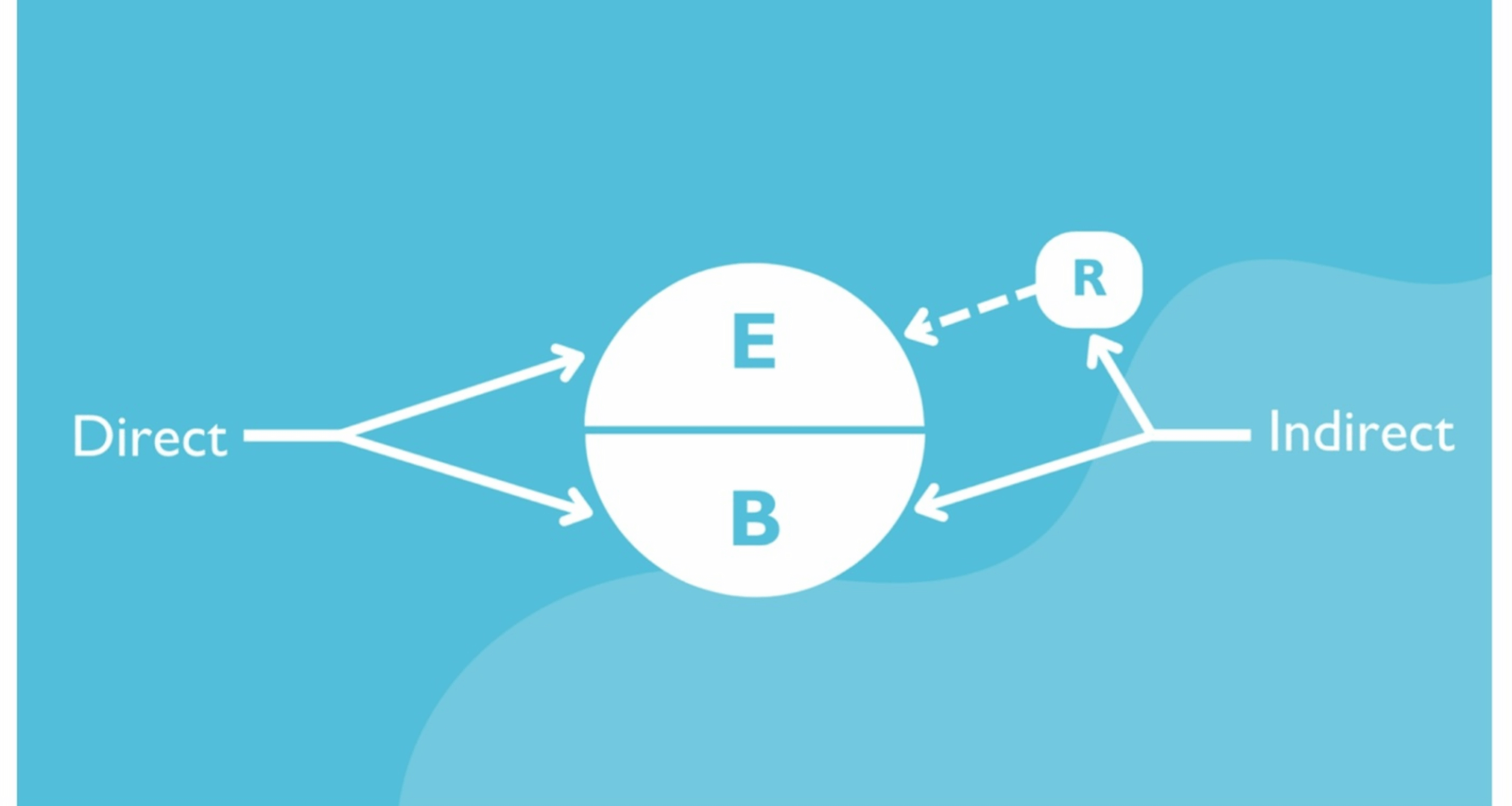

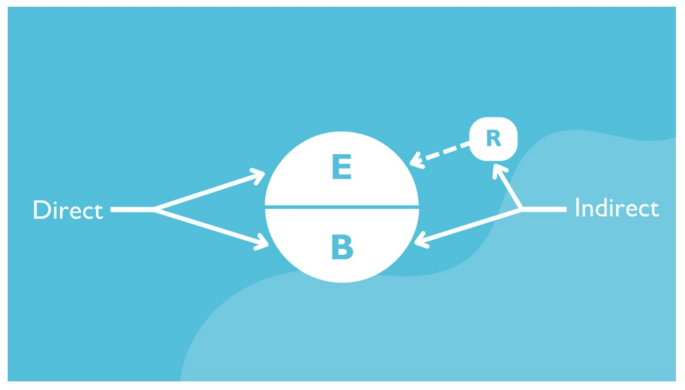

Emotion-facing strategies (Fig. 1) included direct and indirect approaches. Direct approaches acknowledged the role of emotions and actively tried to address them. Indirect approaches usually focussed on developing a strong clinical rapport to reduce patient stress. Patient emotions may have been acknowledged, but they were primarily reduced by increasing the safety and security of the clinical relationship.

Emotion-facing strategies used in surgical practice (E = Emotional dysfunction; B = Biological illness; R = Relationship with patient). The direct approach to emotions aimed to openly diffuse any emotional stressors. The indirect approach prioritised forming a strong relationship and trust with the patient, without openly discussing emotions

Address emotions

Surgeons commonly addressed emotions directly. It was more common in settings where high emotions are expected, such as in cancer clinics, or metabolic surgery. The techniques included directly questioning and exploring emotions, to expanding consultation time, to employing psychologists or nurses who were routinely available for psychological care.

I think in the immediate preoperative period, one of the things that I do in the anaesthetic bay is make sure I acknowledge what I think the patient’s feeling and have a discussion about what they are feeling. – A01.

Prioritising recognition of emotions improved the patient’s experience. It helped developing rapport and maybe improved their treatment outcomes.

I mean, they leave happier from an emotional perspective, but [if] I’m not going to fix them medically… some of them probably walk out happier from an emotional point of view. – K14.

Unresolved emotions also inhibited the surgical treatment process. That is, dealing with emotions in some way improved the efficiency of treatment.

It’s a false economy to try and speed somebody out of a room because a clinic’s running late, because it’s actually going to take you more time in the long term. …Spending a bit of extra time, as frustrating as it can be, will actually be [more] beneficial. – A01.

Pursue rapport (indirect)

Some interviewees prioritised forming a good clinical relationship with the patient. This led to increased trust and better understanding. After multiple interviews, it became clear that some saw this as an emotion-ameliorating technique. A good relationship may reduce some of the fear and anxiety surrounding surgery (clinical partnership) or may transfer some of the responsibility for the good outcome to the surgeon (clinical dependence).

Trust and empathy go along with each other. It will be easier to build up trust if they feel that you can kind of understand what they are worried about and what their concerns are. – M02.

Surgeons talked about the need for rapport as an accepted requirement for treatment. It did not seem to be consciously examined. The idea of good rapport was almost always referenced in the context of a poor treatment outcome. A good relationship was seen as a buffer if the clinical relationship is stressed by unexpected results or complications.

If you want to be selfish about it, it’s absolutely the best possible investment, ‘cause if that person has a leak or a bleed or doesn’t get the treatment effect that you want… well, you are partners, and it’s already set up and you’re already in a partnership and it’s ok. … More importantly it’s a much more rewarding way to practice medicine. It does, it does make it more rewarding. – A04.

Emotion-avoidant strategies

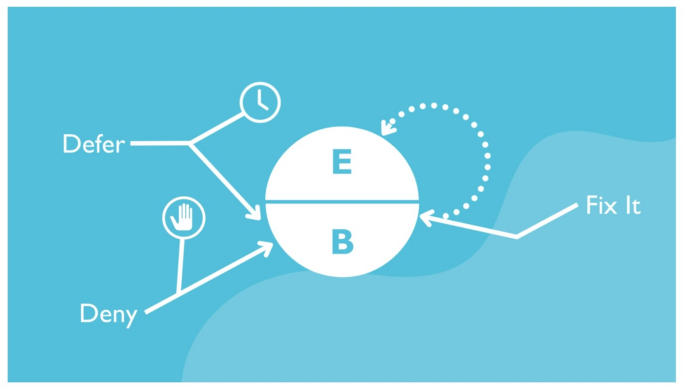

Emotion-avoidant strategies (Fig. 2) were commonly used to reduce the time taken for a consultation or encounter or improve time-efficiency. They were commonly described in life-threatening situations but were not always overtly signposted for patients.

Emotion avoidant strategies used in surgical practice (E = Emotional dysfunction; B = Biological illness). The “Not now” strategy to emotions deferred any resolution of emotions. The “Fix it” strategy focused on resolution of biological illness to reduce overall emotional intensity and avoid the need to deal with emotions. The “Avoid” strategy avoided addressing patient emotions entirely

Not now strategy

The “not now” strategy paused or deferred emotional engagement. It could be done overtly with a verbal request or explanation from the surgeon, or emotion were simply ignored without explanation. This was a common approach in emergency settings, where there may not be enough time to deal with emotional factors due to the urgency of the physical condition. Eventually, this delay must be resolved, or it becomes a variant of avoiding emotions.

I’ve learnt over time to say, right at this moment we need to talk about this a bit more, but I need to organise a couple of things… Can you hold that thought, write anything down that you want to ask me? I’m going to be 15 min, and I’m going to come back and give you some time because I think this is important. – A12.

Ideally, this was discussed openly with the patients as described above, but it also happened without explanation to the patient.

You just have to go, “Well, if this is the path you’re gonna take, you’ve gotta take it now. Sorry.” And then I probably came across as a bitch in that situation… They’re kind of circling the drain at the moment. Like we can sit here and chat about your feelings, and they’re going to be dead? Like, if you want, if you really want to do this, then do this now. – K14.

The benefits of deferral depended on the situation but often related to perceived urgency and triage. If life-threatening or urgent, the biological condition always took priority and emotional and psychological interaction was delayed.

So, I think it’s incredibly important that you recognise from an empathic point of view the difficulty and the stress that they’re in. But I would then argue that that’s not the time for you to then stop… You would need to recognise that, and we need to put that aside for the moment or five. And I guess that’s still showing empathy. – G08.

Fix-it strategy

Emotional intensity was often significantly reduced when there was a successful resolution of the biological or physical problem. Uncertainty, fear, and ongoing symptoms (including pain) were seen as key drivers in ongoing emotional stress. Successful treatment of the underlying physical illness could completely resolve some of these emotions. This approach was described by most interviewees. Surgeons viewed it as particularly useful when they perceived the underlying biological condition to be straightforward and predicted that the outcome of treatment would be successful. The surgeon saw solving the physical symptom as the key to successful treatment, and emotional management.

I think that probably would be my response in that setting. So even if someone came in and said I am really worried about this. Don’t worry, we’ll fix it, rather than what’s got you worried? – A04.

Avoid emotions

The final strategy was to ignore or avoid emotional factors. This approach seemed easier to recognise in others. This showed discomfort with intentionally avoiding emotions. Furthermore, when asked for examples of surgeons who were particularly poor in empathy, this was the typical approach described.

That depends on what you want to be. It comes down to what the surgeon wants to be. If he just wants to be the technical expert, you can have zero empathy. – M02.

Most of the interviewees were uncomfortable with the idea of avoiding emotions, and felt it delivered inadequate care for the patient. It was commonly linked with being indifferent, implying a deficiency or failure. However, it was described as a choice or technique, rather than incompetence. This did not usually equate to being an inadequate or even poor surgeon, if the approach to the underlying physical condition was correct.

In technical terms, the guy who can fix you up but not necessarily talk to you about it in a way that you understand… These guys may get the respect of their patients because they can fix them up, but that is probably not the whole experience that a patient needs to overcome their condition. – M02.

The perceived advantage of this approach was that it was easier and more time efficient for the surgeon. When speaking about other surgeons or hypothetically, the interviewees linked the behaviour with financial advantage due to efficiency gains. Emotional regulation of self and one’s own resources were also suggested as a reason to choose this approach.

Well, if you are the God who provides the care, then patients will probably not bother you as much. And if you have separated yourself from emotional engagement with the patient, then when things go wrong, it’s just that things went wrong. And I don’t have to engage with that distress. – S05.

Value and difficulty of addressing emotions

Addressing patient emotions is seen as a functional approach. Unresolved or unaddressed emotions served as a barrier to many of the surgeons’ tasks, particularly educating patients and having a positive outcome at the end of surgical treatment.

I think acknowledging an emotion, showing an understanding of emotion or even seeking out an understanding of emotion, I think that is a very powerful rapport building tool and almost to me it’s like emotion is, rather than getting in our way, it’s almost like not seeking emotions, there is an opportunity cost there. – A04.

It’s probably hard because I have to keep bringing it back and managing the emotion at the same time as ensuring they’re actually hearing what I need them to hear. – K14.

Barriers to addressing emotions

The reluctance to deal with emotions directly was not ubiquitous. However, there was a general perspective from interviewees that exploration and resolution of emotions is not the core business of surgery. There were perceived barriers to dealing with emotions, which explain why some surgeons spent at least some of their clinical encounters deferring or avoiding participation at this level. The most cited barrier to dealing with patient emotions was time available or the risk of delaying other unrelated clinical tasks.

Let the person talk. Find out what their real concerns are. That takes a lot of time and energy and a lot of us just don’t have that energy or the patience anymore, to just see and wait for the emotions to come and then address them. – M02.

When dealing with urgent or emergency cases, the emotional load was often high, but the time before deterioration of the biological pathology was short. This was a clear conflict, and surgeons openly talked about the compromises they consciously made in those situations.

There’s just less time for you to be able to deal with the emotional side of things in that setting. … in those urgent settings you have to be even more blunt and sometimes you have to push the emotional stuff aside a little bit in order to try and get the message through. – D07.

Surgeons also were not confident of their own skills at managing emotions and overwhelmed at the complex psychological and emotional situations they were exposed to. They felt confident and skilled at dealing with physical illness but felt less well-equipped to manage patients’ distress.

So, I think those that those that deal with greyness … such as psychiatrists or whatever who, that is a big part of their training, I think would feel much more comfortable than the average surgeon surgical registrar. – G08.