A cohort study was conducted to evaluate the effect of stratified first aid skills training on objective skills test scores, pre-post training self-estimate scores and confidence, and training satisfaction of physicians.

Participants

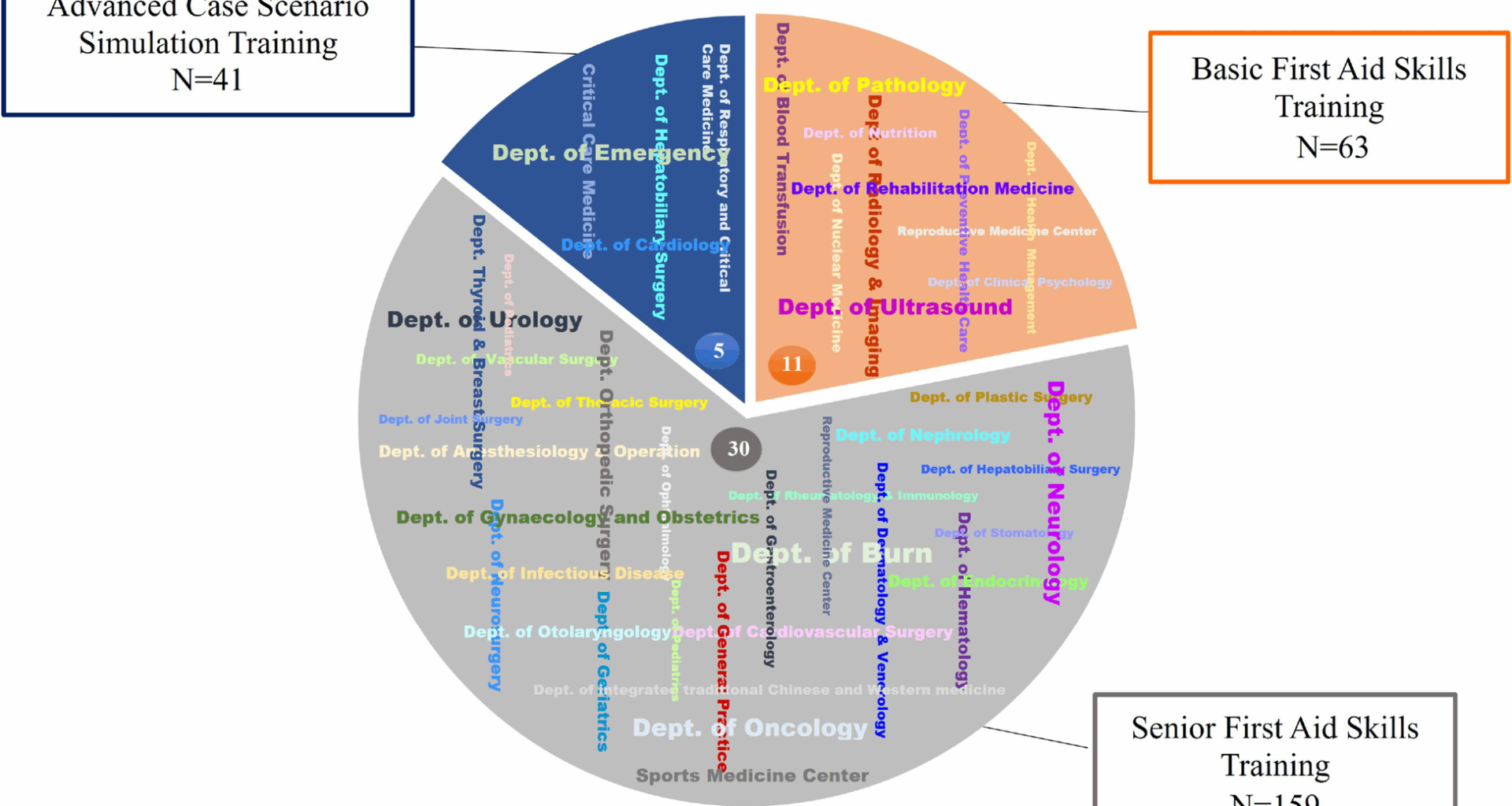

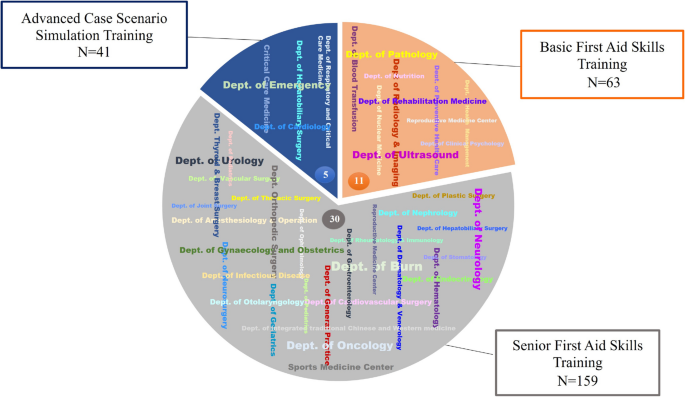

The qualified practicing physicians of clinical medicine in the hospital were eligible for admission to the study. We stratified a total of 263 physicians into three levels according to the clinical working time and different disciplinary backgrounds: basic first aid skills training, senior first aid skills training, and advanced case scenario simulation training. The study was undertaken from July 27th to September 14th in 2023.

Study procedure

The design, authoring of case scenarios, and implementation of the comprehensive simulation-based first aid skills training were carried out by the professors from the Department of Emergency, Critical Care Medicine, Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, and Anesthesiology & Operation of the hospital.

The basic first aid skills training is a single skill module that includes clinical emergency handling reasoning and application, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), automated external defibrillator (AED)/electric defibrillation usage, airway opening, bag valve mask ventilation, Heimlich maneuver, and oral/nasal pharyngeal airway opening (Fig. 2). A total of 63 staff from 11 different clinical ancillary diagnostics departments, including the Department of Pathology, Nutrition, Rehabilitation Medicine, Clinical Psychology, Blood Transfusion, Nuclear Medicine, Ultrasound, Radiology & Imaging, etc., received basic first aid skills training. This training was carried out within 3 h with 8 trainees in each group.

The senior first aid skills training is an integrated module that contains advanced first aid skills and clinical reasoning, which provides for cricothyrotomy, endotracheal intubation, electrical cardioversion, percutaneous tracheostomy, and advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) (Fig. 2). A total of 159 staff with 1–4 years of work experience from 30 different clinical medicine departments, including the Department of Nephrology, Oncology, Urology, Gynaecology and Obstetrics, Plastic Surgery, Geriatrics, Endocrinology, Cardiovascular Surgery, Anesthesiology & Operation, etc., received senior first aid skills training. This training was carried out within 7 h with 8 trainees in each group.

The advanced case scenario simulation training is an integrated multidisciplinary module that combines advanced skills, clinical emergency reasoning, communication skills, and teamwork training. It included how to recognize and treat emergent airway events, cerebrovascular accidents, breathing and cardiac arrest, adverse infusion reactions, pulmonary embolism, chest pain, and acute abdominal diseases (Fig. 2). For the highly comprehensive department with ≥ 5 years of work experience, a total of 41 staff from 5 different clinical departments, including the Department of Emergency, Critical Care Medicine, Hepatobiliary Surgery, Cardiology, and Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, received advanced case scenario simulation training. This training was carried out within 3 h with 5 trainees in each group. The department distribution of participants is presented in Fig. 1.

Department distribution of participants. Footnote: 5:5 Comprehensive departments. 11: 11 Auxiliary departments. 30: 30 Clinical departments

The high-tech mannequins used in ACLS and advanced case scenario simulation training are realistic, anatomically correct, vital signs programmable, and computer-driven, which can monitor and provide care using native equipment and simulate physiological reactions like a real patient.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome measured in this study was the objective skills test; secondary outcomes were pre-post self-estimate scores and confidence, and physicians’ satisfaction, which was measured with training feedback questionnaires. The physicians were required to take an objective skills test at the end of training: the basic first aid group received CPR and AED skills test; the senior first aid group received endotracheal intubation and Advanced Cardiac Life Support (ACLS) skills test; the advanced case scenario group received a clinical reasoning composite skills test. All the skills tests are performed by professors using objective evaluation criteria forms that have been validated in clinical teaching.

The physicians were required to complete the training feedback questionnaires at the beginning and end of the training courses. The questionnaire comprises personal information, self-estimate scores and confidence, and training satisfaction. Participants’ personal information involved in our questionnaire was anonymous. The self-estimate scores encompassed a range of skills across different training levels. The study argued confidence corresponds to the belief that a choice or a proposition is correct based on for solving behavioral tasks that have been designed to probe (Pouget, Drugowitsch, & Kepecs, 2016). The self-estimate confidence was defined by confidence in emergency skills and knowledge, confidence in communication, overall perception confidence, and an open-ended question. The self-estimate confidence and training satisfaction were evaluated using a 4-point Likert scale (Supplementary file). Alphas of self-estimate confidence and training satisfaction scales are 0.829 and 0.934, respectively, and the Bartlett’s Test of Sphericity is < 0.05.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were analyzed as frequencies (percentages), group differences were compared using the Chi-Square test, and bidirectional-ordered categorical variables were compared using the Gamma test. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation and were compared using the Kruskal–Wallis H test, as the data met the nonnormality assumptions. Analyses were performed using SPSS for version 23.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL, USA). Outcomes were considered statistically significant when P < 0.05.