Great Witchingham is not the sort of place you expect cricketers to prepare for an Ashes series.

It’s a tiny village in rural Norfolk, a sleepy corner of eastern England, and home to about 500 people. It’s essentially a collection of houses either side of a mile-long stretch of country road. There’s a pub, a petrol station and a village shop.

There’s a cricket club, too. They play at Walcis Park, just on the edge of the village. And if you happened to watch Great Witchingham play in the summer of 2024, you might have seen the man Australia are hoping will solve their problems at the top of their batting order.

Jake Weatherald was the surprise name in Australia’s squad for the first Ashes Test on Wednesday, but with the top of the home side’s line-up still in a minor state of flux, he is in with a decent chance of facing England when the series starts in Perth on November 21.

His is a great story, of late development, determination and recovery. He was highly rated as a youngster but never quite kicked on, although he was the first player to ever score a century in the final of the Big Bash, Australia’s domestic Twenty20 competition, in 2018. He took a break from the game in 2020 for mental health reasons. He wasn’t getting in his state side, Tasmania, in 2024 and was contemplating leaving entirely.

Jake Weatherald playing in the Big Bash in 2018 (Albert Perez/Getty Images)

He was nevertheless determined to play for Australia one day. So that summer, he got married in Italy, and while his wife Rachel returned home to run her business, he flew to England to play for Great Witchingham.

“I’ve never seen anyone train harder or have a mentality like that,” Jimmy Hales, Great Witchingham’s captain, tells The Athletic. “His mentality was, ‘What am I doing today that gets me closer to playing cricket for Australia?’.

“He’d hit 1,000 balls every day. He had this special spin mat that he’d put on the practice wicket: I was a spinner and he was basically like, ‘Bowl onto this mat and it’ll spin more’, so he could practice playing in really intense conditions. Everything about his game was so well organised and he was so sure in what he was doing.”

Weatherald playing for Tasmania last month (Albert Perez/Getty Images)

Great Witchingham play in the East Anglian Premier League, the highest level of amateur cricket in England. Most teams will have an overseas professional — New Zealand Test player Devon Conway and Australia white-ball specialist Jake Fraser-McGurk are among the names to appear in the league in recent years — and a smattering of other high-profile players.

One of those is Monty Panesar, the former England Test spinner, who became friends with Weatherald in their relatively brief time together at Great Witchingham. “We used to go fishing quite a bit,” Panesar tells The Athletic. “He loves it, it takes him away, calms his mind, and then he can get back into the cricket zone.

“We’d talk about cricket, and he would ask me about what it’s like to play in the Ashes, because that’s his dream.”

This was not Weatherald’s first experience of English amateur cricket. He had spent two summers with Barnsley Woolley Miners, a small club in South Yorkshire, where he averaged almost 60.

But, initially at least, he struggled at Great Witchingham. The club typically start the season with pink ball T20 games, before moving onto longer, red ball matches. “At the start, maybe the first four or five weeks, he didn’t get above 20,” says Hale. “There was a bit of chatter (about his performances), which was mainly because he just kept trying to hit every ball into the car park and he was getting caught every week.”

But then, when the red ball games came, Weatherald flourished. “He just locked into a different mode. He averaged over 50 and was the third-highest run scorer in the league, even though he left (to return to Australia) seven or eight weeks early.”

“He was getting out on these soft, green wickets,” says Panesar, “holing out into deep cover or whatever, but once the wickets got harder, he played some unbelievable innings.”

The general standard of play was beneath what Weatherald would be used to, but high enough that a player of his level couldn’t just turn up and smash a hundred every week. He ended up averaging just under 40, with a highest score of 142.

Weatherald took it very seriously, to the point where there was some minor friction with team-mates as he provided robust feedback.

“He’s a big personality, and with that sometimes came a level of intensity where if someone wasn’t pulling their weight, he would let them know,” says Hale. “It created the odd challenge for me because you’ve got blokes playing who are going back to work on Monday and he’s getting stuck into them because they’re not putting the effort in. But his mentality was, ‘If we’re here, we’re here to win’.”

Hale recalls one meeting in which they were discussing an opposition with a spin-heavy bowling attack, who he thought would attempt to tie the batters down and frustrate them with a low scoring rate. He discussed a few different approaches, then turned to Weatherald. “He said, ‘Well, if I put him into the next field first ball, that’s his problem now’.

“He would always walk out to bat with his chest out, as if he was trying to create a bit of aura. He would be more upset with himself if he blocked three balls and got out trying to hit the fourth for six, than if he had tried to do it first ball.”

Away from the game, he was a popular member of the squad. At one club social, he took charge of the music under the moniker ‘DJ Teriyaki Tofu’. He decided quite early on that Panesar’s dress sense wasn’t to his tastes, so he took him clothes shopping in London.

“He ended up becoming my stylist,” Panesar says. “He’d always just say, ‘I reckon this looks better on you’, and he really enjoyed it. He liked quirky, funky, baggy clothing. I would just say, ‘Yeah, just dress me up’.”

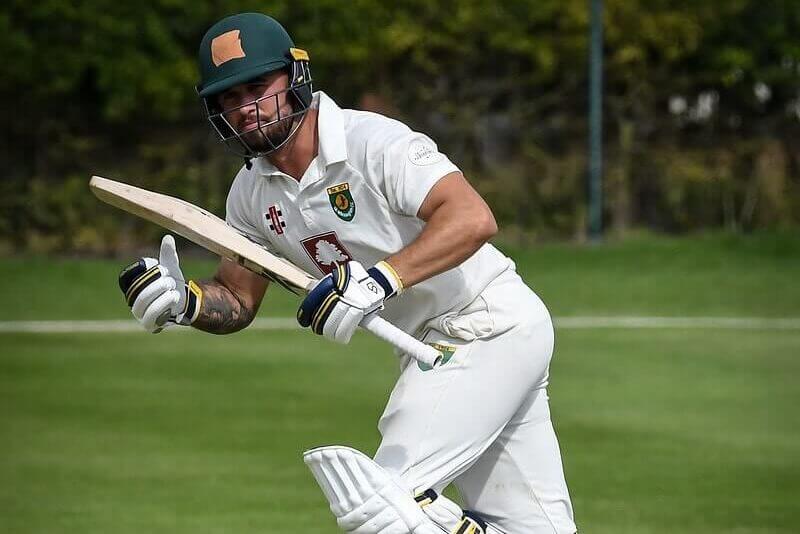

Jake Weatherald playing for Great Witchingham (Photo courtesy of Great Witchingham CC)

From fashion stylist to potential opener. And Hale and Panesar think he could be a dangerous prospect for England’s bowlers. “In a session, he could completely take down an attack,” Panesar says.

“Jake’s going to score at 70, 80 per 100 balls,” says Hale. “His best scores and moments in his career have come against high-speed bowling, and obviously they’re expecting England to play Jofra Archer, Mark Wood and Brydon Carse.”

That’s part of the reason that the player Weatherald is most readily compared to is David Warner: both are compact, aggressive, left-handed opening batters who are capable of taking the game away from the opposition.

Weatherald returned to Australia after his stint with Great Witchingham and piled on the runs for Tasmania. With 906 in 18 innings at an average of 50.33, he was the top scorer in the Sheffield Shield. Given the uncertainty over who will partner Usman Khawaja at the top of the order, with Nathan McSweeney and Sam Konstas now seemingly discarded, it was difficult to ignore Weatherald’s numbers.

Was it all because of his stint at Great Witchingham?

“I told a few of the boys that prior to my captaincy, where was he?” jokes Hale. “I think his biggest challenge will be going from a state cricketer to an international cricketer in the biggest series. That’s going to be pretty intense, and it feels like the one spot on the Australian side that everyone’s got an eyeball on.”

At 31, Weatherald has taken longer than most to get to the top. And most also don’t usually go via a tiny village in the east of England. But perhaps that will make him appreciate the opportunity even more.

Remember the name. They certainly will in Great Witchingham.