This is The Takeaway from today’s Morning Brief, which you can sign up to receive in your inbox every morning along with:

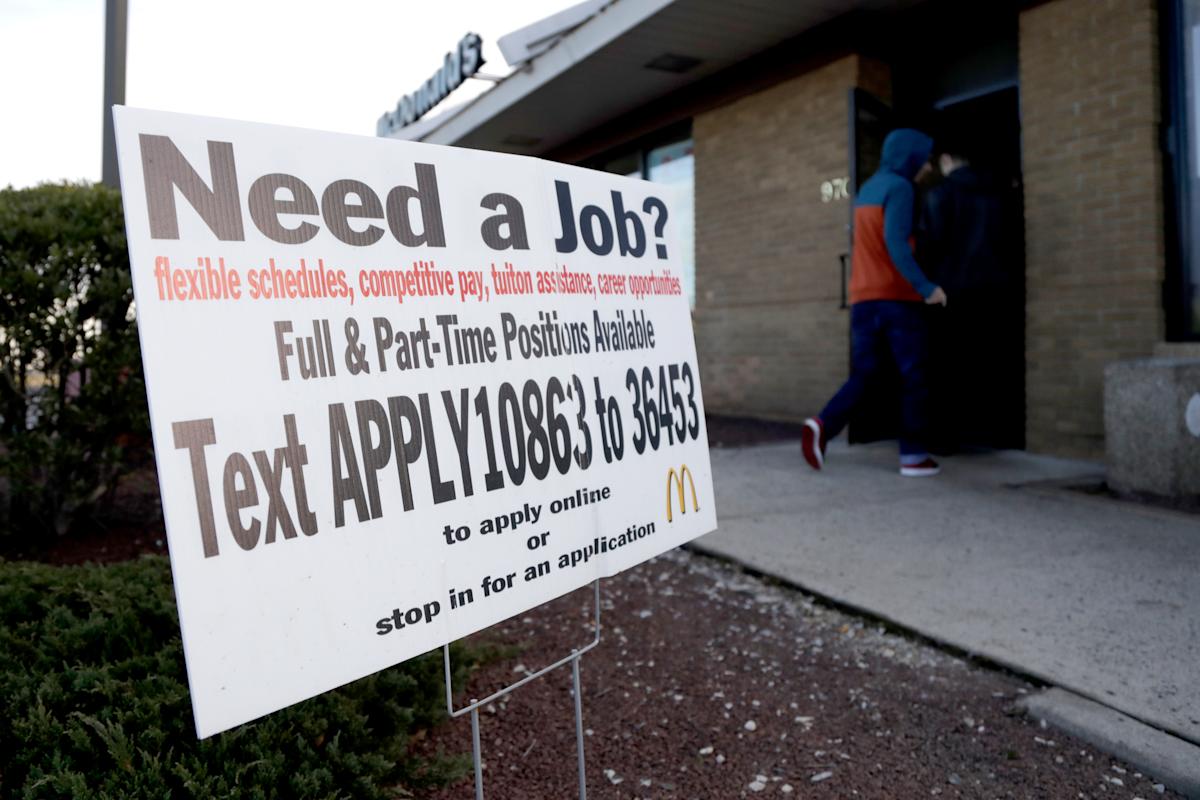

For the first time since midsummer, the country’s private employers added jobs. A positive reading ending a streak of red helps ease concerns about a crumbling labor market. Still, the reading continues to mark a slowdown — even “good” news can confirm weakness.

But perhaps even more frustrating to some is that the data cast more uncertainty on the current economic state of play.

ADP Research data released Wednesday showed an increase in private-sector payrolls of 42,000, reflecting a halt to the job shedding found in August and again in September. The modest growth, however, isn’t enough to change the widely held perception that the job market is softening and may be in trouble.

The ADP report dropped as the government shutdown became the longest in history, which is delaying the release of crucial economic measures, including the all-important government jobs report. Policymakers, business leaders, analysts, and investors have already missed out on the monthly reading from September. And by the end of this week, when the October numbers were scheduled to land, the public will be wading through a two-month blackout of official payroll data.

Other indicators released this week added to the uncertainty and the sense that the US economy, at the moment, defies neat labels. Big changes in the labor market, even without the most important readings, can still be felt. But the shutdown and data blackout make it much harder to see the big picture — as any central banker with a platform right now will note.

US manufacturing contracted for an eighth straight month in October, according to data from the Institute for Supply Management, which showed longer deliveries and lower levels of new orders as the sector navigates a new tariff regime.

Meanwhile, higher service sector output and a firm rise in incoming new business also came with a souring outlook, according to the S&P Global US Services PMI, published on Wednesday. The survey showed confidence about the future fell to a six-month low.

An economic picture, as perceived through a very narrow stream of data, resists categorization as prices rise due to tariffs, the labor market slows down, and corporations and individuals continue to feel the effects of a K-shaped economy. Amid all that, it’s hard to know where we stand. It’s no wonder that the certainty of a December rate cut has faded as more and more Fed officials wonder what’s going on. Inaction is looking more like a solution.