LAS VEGAS — The top of his refrigerator is crowded with white plastic bottles, neatly aligned in rows, so snug that another couldn’t fit. The bottles are filled with pills and powders — an assortment of vitamins, herbs, proteins and minerals. Vitamin E. Vitamin D. Ashwagandha. Black seed oil.

“Everybody thought I would be dead by now,” Spencer Haywood, 76, said from the living room of his Las Vegas home. “When you all think I’m croaking, I’m going to be able to say I stood for something.”

In 1971, he did stand for something. As a 21-year-old, he sued the NBA for the right to join the league despite its rule requiring players be four years removed from high school. The case went to the U.S. Supreme Court, with Haywood arguing the NBA’s stance violated the Sherman Antitrust Act.

He won, paving the way for a generation of talent to enter the NBA no matter their age or college standing. In 2005, the NBA and the NBA Players Association passed a rule that players must be 19 years old and one year removed from high school to be drafted, but Haywood’s 1971 ruling is the benchmark that allowed some of the game’s greatest young talent to pursue their dreams.

“LeBron James, Kevin Durant, Kevin Garnett, Dwight Howard, Carmelo Anthony … it goes on and on,” Haywood said. “I did so much for them individually.”

Today, Haywood is digging in for one final stand: He wants the NBA to recognize the struggle from his court battle by proclaiming the outcome “the Spencer Haywood Rule.” His fight 54 years ago helped usher in billions of dollars for the players — and also the league — but Haywood laments he has been left with only emotional scars.

“Even talking about it hurts me,” Haywood said.

He is normally the most jovial of characters. He laughs often, and sometimes he’s the only one who knows why he is laughing. He wears colorful beaded necklaces and bracelets, and they rattle as he enthusiastically tells stories of dinners with Michael Jordan, golfing with Julius Erving, the latest book Kareem Abdul-Jabbar has sent him, or his most recent hang with one of his favorite people, Shaquille O’Neal.

But he turns serious and emotional when the subject turns to his two fights — the Supreme Court case and his push today to have that ruling recognized.

“My clock is ticking, and I don’t want to go out like this,” Haywood said. “The one thing I want, and I’ve been asking now for the last four years, is to have my name on the ruling: it’s the Spencer Haywood Rule. There are 480 players in the NBA, and 468 of them don’t know who the f— I am. I want the players to know there was once somebody who cared enough to put their life and career on the line.

“But, they don’t know.”

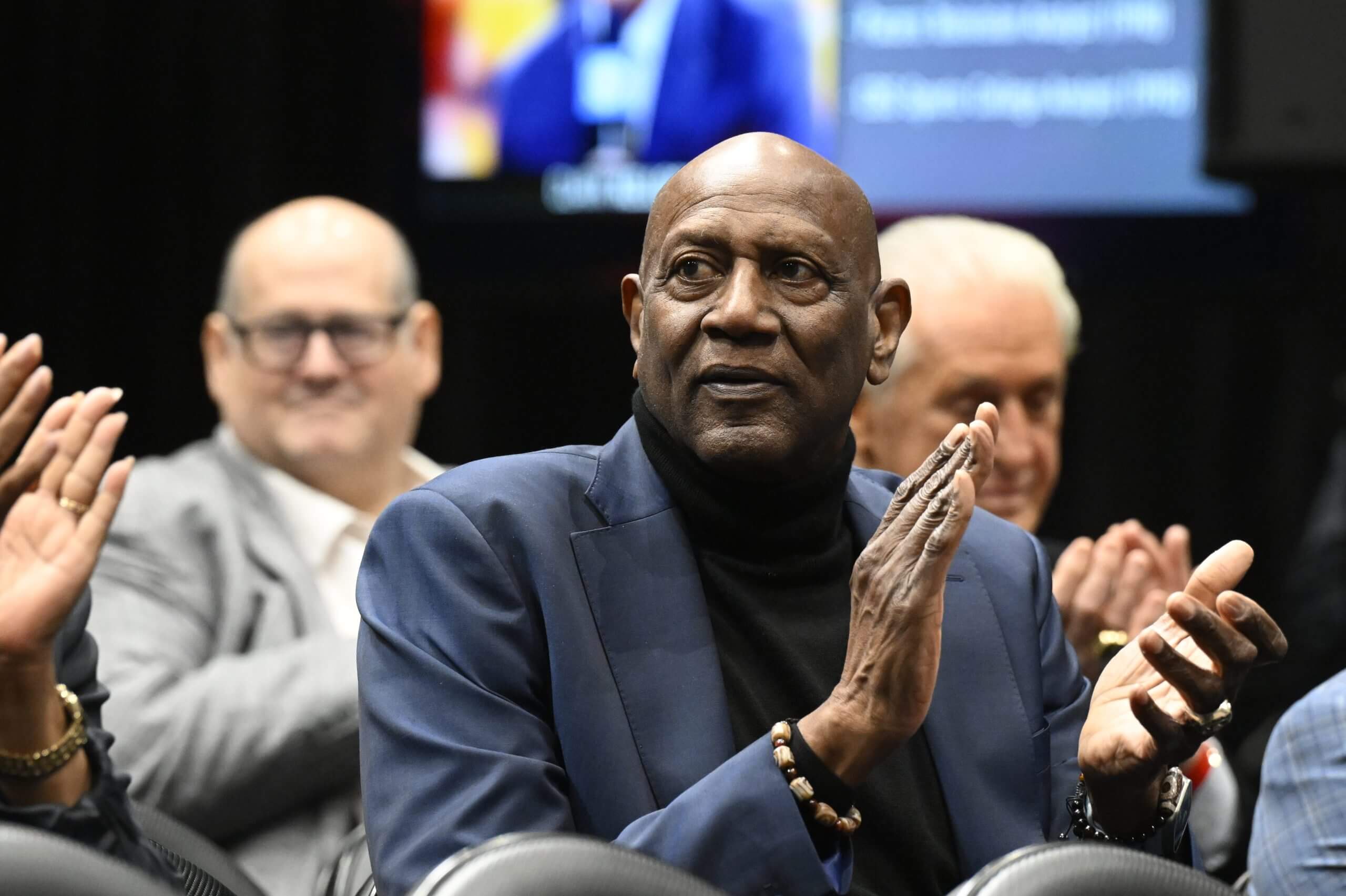

Spencer Haywood, pictured last February, hopes the NBA recognizes his landmark U.S. Supreme Court case by naming a rule after him. But it appears to be a long shot. (David Dow / NBAE via Getty Images)

He puts on his size-17 Nikes in preparation for the gym and quips that his motive behind all the vitamins and gym visits is so he can be spry enough to accept the honor in person, if it ever comes.

It’s a day that likely will never happen. Even though NBA nomenclature attaches players’ names to rules — Larry Bird rights (allowing a team to go over the salary cap to sign its own free agent), the Trent Tucker Rule (at least 0.3 seconds must remain on clock for a player to attempt a shot), the Oscar Robertson Rule (allowing a player to become a free agent) — an NBA spokesperson says the league does not officially name rules after players.

Still, Haywood tells his story to anyone who will listen, lobbying for a sympathetic ear that can help push his pursuit over the finish line. He said he has frequent conversations with NBA commissioner Adam Silver, and those talks leave him hopeful, yet chagrined.

“I just thought this year was going to be the year that Adam would call me and say, ‘Hey … I declare this is your rule,’” Haywood said with a sigh.

On the surface, it seems like a curious fight for such an accomplished man. His fireplace mantle is as crowded as the vitamin collection atop his refrigerator. There is the trophy from his 2015 induction into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame, flanked by medals, plaques and framed jerseys from a 13-year NBA career with five teams that featured four All-Star appearances and four All-NBA selections.

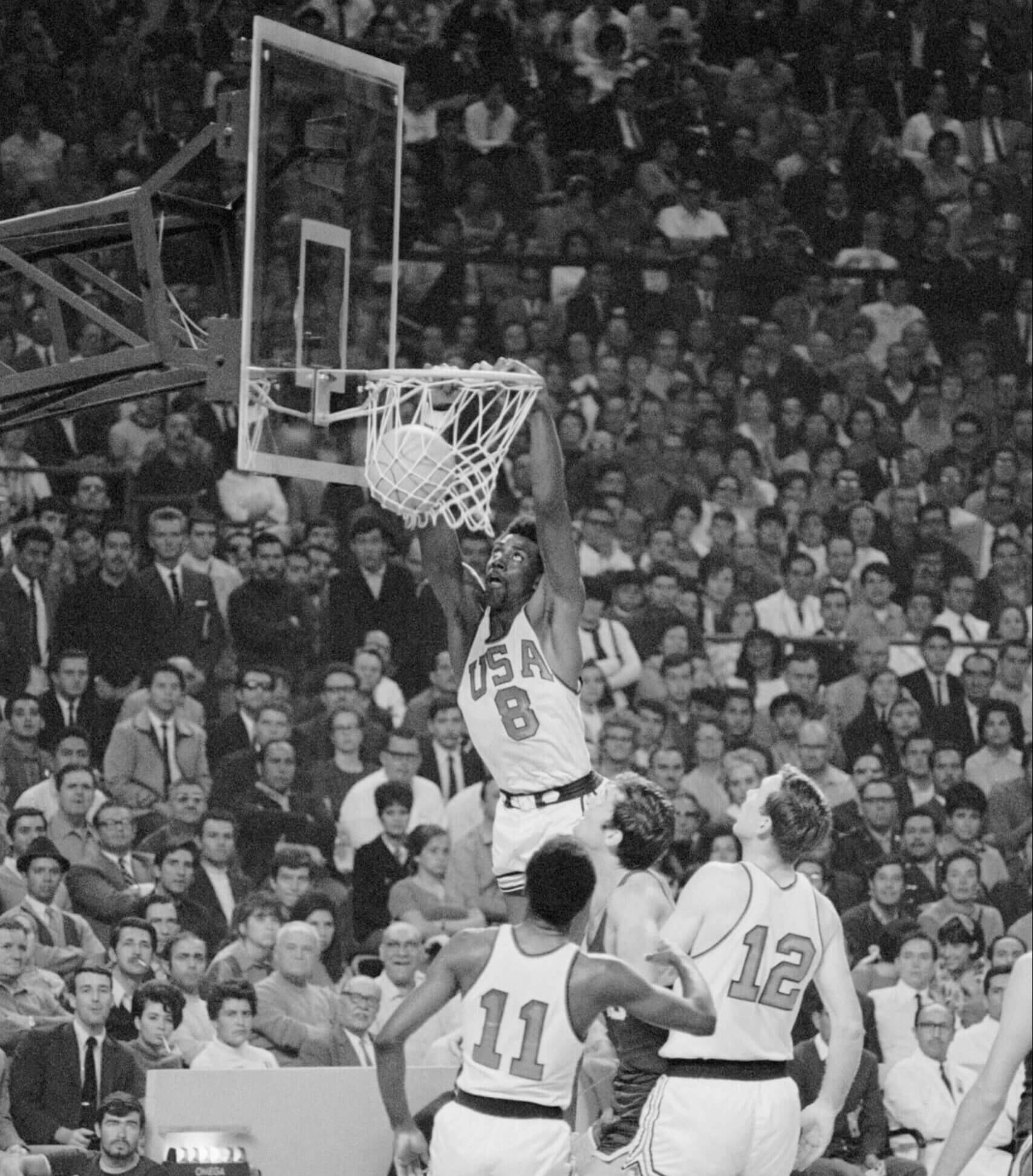

At 19, he became the youngest men’s Olympic basketball player to put on a Team USA uniform. He then led the United States to the gold medal in the 1968 Summer Olympics in Mexico City. Haywood scored 145 points in the tournament, an American record that stood for 44 years until Durant scored 156 points in the 2012 Summer Olympics in London.

Then as a rookie with the ABA’s Denver Rockets for the 1969-70 season, he led the league in scoring (30 points) and (19.5, an ABA record) and also was named Rookie of the Year, MVP of the All-Star Game and MVP for the season. Wilt Chamberlain is the only other professional basketball player to win those three awards in the same season.

Haywood’s fireplace mantle has framed jerseys from Seattle, New York, the Los Angeles Lakers and Team USA, a homage to the 6-foot-8 forward who once soared above defenders for dunks and finger rolls, then took out souls with a shot he seemingly couldn’t miss: a turnaround jumper from the baseline. All the while, he gobbled rebounds with massive hands. He was, as Haywood reminds, “the Original Superman” before O’Neal and Howard tried on the moniker.

Haywood had his jersey retired in Seattle in 2007, but his early days with the franchise were marked by discord. “It was the most traumatic thing that could happen to a young person,” he said. (Terrence Vaccaro / NBAE via Getty Images)

It would be easy to fade into the twilight of his life, reflecting on his accomplishments on the mantle, content that he is financially set, proud of the accomplishments of his four daughters who have given him four grandchildren, whose photos fill his phone.

However, there is nothing easy, nothing surface-level, about the “why” of his fight. His why comes from a collection of places in his past. The Mississippi cotton fields, where he lived with the anger and shame of having a mixed-race sister, the result of his mother being raped by a White neighbor. The dorm rooms at the 1968 Olympics, where he forged a lifelong friendship with John Carlos, who awakened him to the ideas of justice, equality and taking a stand. And the Las Vegas hospital room, where he lost his wife of 36 years, Linda.

His why traces back to legacy, and the importance of standing up for yourself and honoring others.

“I’ll tell you why this is important to me,” Haywood said. “Knowing history somewhat, I see that these types of things are just erased throughout history when it comes to a Black athlete or Black person. I just want my due.”

At the 1968 Olympics, Haywood remembers the American athletes being summoned for a meeting: Jesse Owens, the track hero from the 1936 Summer Olympics in Berlin, was going to speak in an effort to cool the rising temperature inside the village.

Back home, there was a hurricane of friction, with racial tension and anti-Vietnam War protests creating a volatile and unstable environment. It was the nightly topic in the dorm rooms of the Americans as athletes gathered to discuss the unrest and direction of the country. Led by track stars Carlos and Tommie Smith, there were talks of an athlete boycott to show unity.

In the crowd for these meetings was a wide-eyed 19-year-old basketball player from the cotton fields of Mississippi.

Haywood was the youngest player to make the Olympic basketball roster, but he also led the gold medal-winning team in scoring through the 1968 tournament. (Bettmann)

Carlos, who was 23 at the time, could see an overwhelmed and impressionable kid.

“John Carlos would look at me, and say, ‘G– damn, Spencer, you are so country!’” Haywood remembered.

Said Carlos: “He was very, very young. He didn’t know what life was about, and he was out there basically by himself. So, I kind of took him under my wing.”

Carlos spoke about the concepts of a society functioning with harmony, love, humility and equality, and he pointed out how as Black men, their country was not affording them those basic qualities. Haywood was not long removed from picking cotton with his mother in Silver City, Miss., and he had become accustomed to walking with his head down, to not make eye contact with Whites.

As Haywood listened to Carlos, he had an awakening.

“Being at the Olympics, listening to John Carlos, it made me aware,” Haywood said. “It molded me.”

But it wasn’t until Haywood settled in for the meeting to hear Owens speak that he understood exactly how taking a stand looked, and sounded.

“Jesse Owens gave us this nice spiel about how appreciative we should be when we get home and how we should be grateful we were representing our country,” Haywood said. “And then John Carlos, stood up … and WHOA!”

In the middle of Owens’ speech, Carlos interrupted and challenged the star. He reminded Owens of how he was disrespected following his return to America from the Berlin Olympics and how he was still treated as a second-class citizen. Sure, he was feted as an Olympic star, but he couldn’t find a job, couldn’t use the same elevator as Whites, couldn’t use the same water fountain.

Hearing Owens take the corporate line, ignoring his own plight and the current racial climate, infuriated Carlos. He said he respected Owens as much as he did his own father, but he couldn’t let him go on.

“He was talking to us like we were wind-up toys and that we shouldn’t have concern about the well-being of the communities that we live within,” Carlos said. “It was like that statement a commentator made a couple years ago: Just shut up and play. That was his mentality in so many words, and I was totally against that.”

As Carlos stood his ground against the legend, a rallying cry emerged from Carlos’ stand: You expect me to live in this country, but have no voice in this country.

It was a seminal moment for Haywood, who became emboldened by Carlos’ strength and unwavering principle.

“I had never been around a defiant brother,” Haywood said. “As a Black man, I ain’t never heard nobody talking back to people like that. I was like, ‘Wow.’”

Said Carlos: “When I challenged Jesse in that meeting, Spencer’s eyes opened real wide … and his ears, as well.”

Haywood and John Carlos, pictured in May 2022, remain close to this day. “Being at the Olympics, listening to John Carlos, it made me aware,” Haywood said. “It molded me.” (Ethan Miller / Getty Images)

After winning gold, Haywood returned to his home in Detroit, where he began to frequent Vaughn’s Book Store, the first Black-owned bookstore in the city. He soaked up all he could about Black history. Throughout his readings, Haywood couldn’t get one of Carlos’ messages out of his head. Carlos didn’t just talk about the importance of eclipsing the metaphoric wall, he talked about the importance for everyone to make it over the wall.

Two years later, when the NBA tried to prevent him from suiting up with the Seattle SuperSonics because of his age and college standing, Haywood recognized he had encountered his own wall. He would take on the fight, and not just for himself. Everyone would get over the wall.

“I just knew I was in the right place at the right time,” Haywood said.

Haywood might have been in the right place at the right time during the 1970-71 season, but nothing during that first NBA year felt right.

Coming off a Rookie of the Year season in the ABA, he had a contract dispute, and in December 1970 he was signed by Seattle owner Sam Schulman despite the NBA’s rule that players must be four years removed from high school. Even though Haywood had played a year of professional ball in Denver — the ABA adopted a hardship rule that allowed college players to enter early if poised with financial troubles — the NBA ruled him ineligible because he had only two years of college. Instead of returning to the ABA or going overseas, Haywood took the league to court.

NBA players gave him the cold shoulder. If he won the suit, it meant an influx of young talent would fill the league, potentially nudging some of the current players out of a job. And Haywood said he believed the league feared, if the rule passed, that fans would not accept rosters that would become filled with Black players.

At road games, fans hurled insults and beer bottles as the loudspeaker announced he was an ineligible player. It wasn’t until January when Haywood received an injunction that allowed him to play while the court process played out. For some, the idea that a player — a Black player at that — wouldn’t adhere to the league rules was an egregious example of entitlement.

Even in Seattle, at the newly built Washington Plaza Hotel downtown, he was slugged in the stomach as he went to the restroom.

“It was the most traumatic thing that could happen to a young person,” Haywood said. “Going through the court cases, getting hit in the stomach, getting yelled at from the stands. It wasn’t just a battle in the courts, it was a battle outside the courts.”

All the while, Haywood was this attraction, a fascination that captivated Seattle. He hosted a weekly jazz show on the radio. He hosted Miles Davis and his band at his condominium. And he was on billboards around the city.

“He became this immediate cultural icon,” said Rick Welts, who today is the CEO of the Dallas Mavericks but in 1970 was the SuperSonics’ ball boy. “It was the age and circumstances surrounding his arrival and his defiance of the NBA and the rules at the time. He automatically became a lightning rod of reaction within the city.”

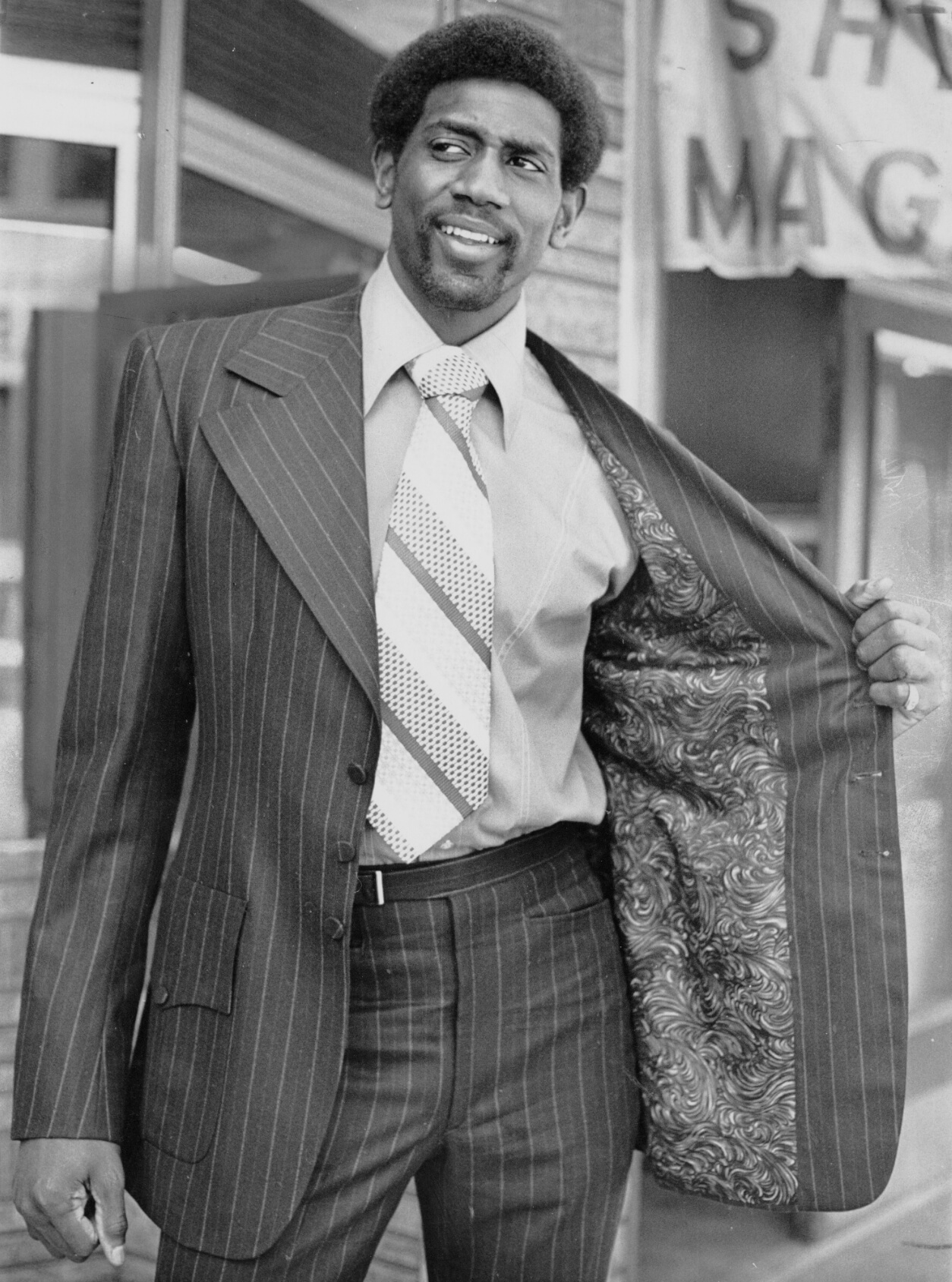

Haywood, shown in April 1970, was an instant star in the ABA before hopping to the NBA and taking the league to court. (Duane Howell / The Denver Post)

Welts was four years younger than Haywood, and on a Sonics team mostly filled with veterans, Haywood gravitated toward hanging out with Welts more than his teammates. Welts said Haywood never let on that he was hurt or affected by the turmoil around his case.

“Clearly there was an inner strength there, but he was never one to be overly emotional about what was going on,” Welts said. “But you could see the strength of his character.”

Suing the league was a bold move for a 21-year-old at the height of his game. Lose, and he likely had to go overseas to play and risk being ostracized by the NBA. Still, he persisted.

“That’s why I wish players today knew that there was somebody who went to battle for them, risked their career for them, and who has the scars,” Haywood said.

Added Welts: “He really was a barrier breaker, and I don’t think he gets the recognition for that. I’m not sure today’s players have that sense of history or his role, which is a shame. He’s a very historic figure in the history of our game, and I don’t think history has really celebrated his role probably the way he deserves to have it celebrated.”

At his Las Vegas home, a Buddha statue overlooks the shallow pool in his backyard. He chuckles, saying he asks the Buddha to bring him luck in his quest to be recognized.

“I have no shame in my game,” Haywood cackled. “I need all the help I can get.”

He is consumed with time, and how it is ticking, even as he believes he is prolonging his life with his daily vitamins and a pescatarian diet. The sands of his hourglass have become louder in a home that is suddenly so empty.

Three years ago, his wife of 36 years, Linda, died from an autoimmune blood disorder. He said he still struggles with her absence.

Haywood and his wife of 36 years, Linda, who died in August 2022. “Her world was me getting my recognition,” he said. (Courtesy of Spencer Haywood)

When they met at an art museum in Detroit, he had been divorced for 11 years from supermodel Iman. In Linda, he found comfort that, like him, she was from Mississippi. He couldn’t help but notice that she had strikingly similar features as his mother. Linda was a nurturer, but also was a sharp and independent woman who was an executive at Blue Cross Blue Shield.

They led a simple and quiet life as they raised three daughters. They dined, danced and listened to music. But mostly, they talked, and when she would have her way, they would drive 35 minutes to Lake Las Vegas.

“There was this waterfall (next to a golf course), and she would always want to go out there for some reason. It was like she was drawn to it,” Haywood said. “We would sit down on this rock and talk for hours. That’s when you know you’ve got the right one, when you can just sit and talk, man, you know?”

In August 2022, Linda passed. She was 62.

Haywood thinks about her daily, and he gets choked up talking about her as he drives from his home in the Southern Highlands and down Interstate 15. For about a mile, he drives in silence until he clears his throat and reverts back to his favorite shtick: humor.

“Yeah, I miss her every day. Because I mean, now I gotta make my own protein drink. I gotta cook my own vegan food. I’m like, ‘What kind of crap is this?’” Haywood said through a laugh.

It’s not just the empty house that triggers his emotion. She was largely his voice. She championed his fight to have the NBA name the Supreme Court ruling after him, helping to write his letters to the league.

“Oh, she was into it,” Haywood said. “Her world was me getting my recognition.”

Keeping his fight alive gives him comfort, a reminder of their connection, their combined effort.

For years, Haywood has been seeking help to understand why his mind seems so entangled with frustration, anger and recognition. He sees a therapist regularly.

“I have a lot of stuff pushed down in me,” he said. “A lot of this stuff we’re talking about, I’ve never talked about. It’s been down in there so long.”

He traces his three-year addiction to crack cocaine — which led to his dismissal from the Lakers in 1980 — to his anger about his mother’s rape, which happened before he was born. He harbored confusion and embarrassment of not being able to say anything about having a mixed sister.

He still wrestles with his identity, in one breath calling himself “just a cotton picker” or “all this from a farmer who grew up in pig sh–,” but in the next breath saying, “I think my significance is far greater than anybody’s in NBA history.”

He still talks with Carlos, and those conversations help reinforce his stance that his fight is worth it … that he is worth it.

“Fighters,” Carlos said, “are the ones who really make the change.”

Haywood, who received his Hall of Fame jacket as part of the Class of 2015, is still seeking one last bit of recognition. “I have peace, but I don’t have my athletic peace,” he said. (Nathaniel S. Butler / NBAE via Getty Images)

The NBA says it understands and appreciates Haywood’s journey, and it wants to celebrate him, which is reflected in the more than 100 events the league has asked him to appear as an ambassador. Haywood has appeared at so many events he said he considers Kathy Behrens, the NBA’s president of social responsibility and player programs, a friend.

“His story is certainly one we want players to understand,” Behrens said. “The decisions he made, and the success he had in the courts changed the trajectory of a lot of players’ own journeys. … It’s almost hard to understand some of the things he fought for and was successful at just given the changes (in college and amateur basketball) that have happened, but it’s still an important part of our history.”

But when it comes to the league naming the ruling after Haywood, a spokesman for the league essentially throws his hands in the air and says it’s never been the NBA’s practice to attach players’ names to rules. Haywood counters by pointing to the league’s decision in 2022 to name end-of-season awards after Michael Jordan (MVP), Wilt Chamberlain (Rookie of the Year), John Havlicek (Sixth Man of the Year), Hakeem Olajuwon (Defensive Player of the Year) and George Mikan (Most Improved Player).

In October, Haywood represented the NBA Players Association and appeared before Sens. Richard Blumenthal (Conn.), Cory Booker (N.J.) and Maria Cantwell (Wash.) in a discussion about whether the SCORE Act benefits or restricts student athletes’ compensation and benefits. Haywood argued to protect the athletes, and not the establishments that are making money off the athletes.

As Carlos noted, Haywood again is fighting the fight for others, making sure everyone gets over the wall. In the meantime, Haywood stays on the front line, pushing, pleading, waiting for news from the NBA that recognizes his own fight, his own contribution.

He laughs often, and he lives well, but yet is he unfulfilled.

“I have peace, but I don’t have my athletic peace,” Haywood said. “What I stood for … Tommie and John got theirs; I’m the only one who hasn’t.

“It’s right around the corner.”