What could possibly connect Man Ray and Max Dupain? One was a leading avant-garde artist of the twentieth century, the other a photographer whose work helped define a distinctly Australian modernist vision. They have more in common than one might think. Coming to photography at very different moments in their lives, they nonetheless share a commitment to experimentation and form. Both were active in a pivotal time when the language of modernism was being rewritten through the camera, and their experiments reveal unexpected points of contact across both geographical and cultural distance.

The lead-up makes sense and feels long overdue. It has been more than two decades since Man Ray had a substantive exhibition in Australia: in 2004, a touring exhibition titled Man Ray at the Art Gallery of New South Wales, curated by Judy Annear and Emmanuelle de l’Ecotais. While Dupain is consistently shown at the State Library of New South Wales, which holds his archive of negatives related to his commercial work, his last major solo exhibition was Max Dupain: Modernist in 2007. It would be remiss not to mention Heide’s popular 2023 survey of works by Lee Miller, the American photographer who both modelled for and worked closely with Man Ray in Paris. Along with Miller, photographer Olive Cotton—Dupain’s collaborator, contemporary, and first wife—features in this exhibition as a marginal figure, a reminder of the partnerships and artistic exchanges that supported both men’s practices.

Installation view of Man Ray and Max Dupain, Heide Museum of Modern Art, 2025. Photo: Ruby Taylor

The exhibition, simply titled Man Ray and Max Dupain, brings together over two hundred prints, archival material, and artist’s books, mainly from the 1920s and 1930s, a period when Surrealism reached its height in Paris and modernist photography was taking shape in Australia. Split between Paris and Australia, this isn’t a story of centre meets periphery (thank God), and co-curator Lesley Harding knows this perfectly well. In her catalogue essay, she cites Rex Butler and A.D.S. Donaldson’s UnAustralian Art project, noting that “Australian art is part of, and belongs to, the rest of the world.” In this way, Harding and co-curator Emmanuelle de l’Ecotais appear confident enough to present the two photographers as equals. Here, in 2025, Max Dupain and Man Ray appear to stand on equal footing. So, how do they compare?

While it’s not made overtly explicit, an early connection can be found in the first main room of the exhibition, where pages from a comb-bound copy of the artist’s book Man Ray Photographs 1920–1934 are concertinaed across a long showcase. Its unbound pages include examples of the woman-as-muse, a self-portrait, and a textual readymade by Marcel Duchamp’s female alter ego, Rrose Sélavy, titled Men Before the Mirror. As Rrose Sélavy writes, “Many a time the mirror imprisons them and holds them firmly,” suggesting that the mirror, and by extension the photograph, does not simply reflect but gazes back. The following year, in 1935, Dupain was asked to review the volume for The Home, a popular lifestyle magazine, for its October issue. He begins by declaring: “The importance of Man Ray in photography is analogous to that of Cézanne in painting, and it does not seem imprudent to prophesy his enjoyment of an equivalent greatness.” Examples of the magazine appear in a separate room dedicated to both artists’ fashion and advertising work. It is a publication in which Dupain played a significant part in shifting its relationship to modernism; many of the photographs he made for and published in The Home helped steer the visual style of the publication toward a more modernist approach. In his review of Man Ray’s volume, he concludes by writing, “He is alone. A pioneer of the twentieth century who has crystallised a new experience in light and chemistry.” The review leaves little doubt about Dupain’s admiration for Man Ray, whose artistic innovations the exhibition positions as a criterion for Dupain’s own modernist ambitions. Photography’s position within this exchange is especially telling: of all systems of representation, it carried a particular privilege in twentieth-century culture, its authority drawn from its technological and scientific origins (“light and chemistry”). This dialogue between influence and adaptation continues just across the room.

Man Ray, Eye and Tears, 1932, printed 1972, gelatin silver photograph, 20.6 x 24.7 cm (image), 20.6 x 25.5 cm (sheet). National Gallery of Victoria, Melbourne, purchased 1973

Opposite the artist’s book hang Man Ray’s Glass Tears (1932) and Eye and Tears (1932)—the close-up, mascaraed eyes of a fashion model with glass beads dotted below them—exemplary works of the Surrealist movement that introduce the shared thematics of both artists. Even here, an Australian connection can be made. Eye and Tears was reproduced in a February 1934 issue of The Home, paired with an article on salads, accompanied by the image caption: “An Unusual Study from Photographie.” The Home’s editor, Sydney Ure Smith, was an advocate for modern design and photography in interwar Australia, and his interest in sourcing avant-garde material from abroad reflects a broader ambition to align Australian culture with European modernism. Photographie was an avant-garde French photo magazine, and its citation signals that the mode of transmission—the circulation of avant-garde imagery through popular media—was perhaps as significant to Ure Smith as the images themselves.

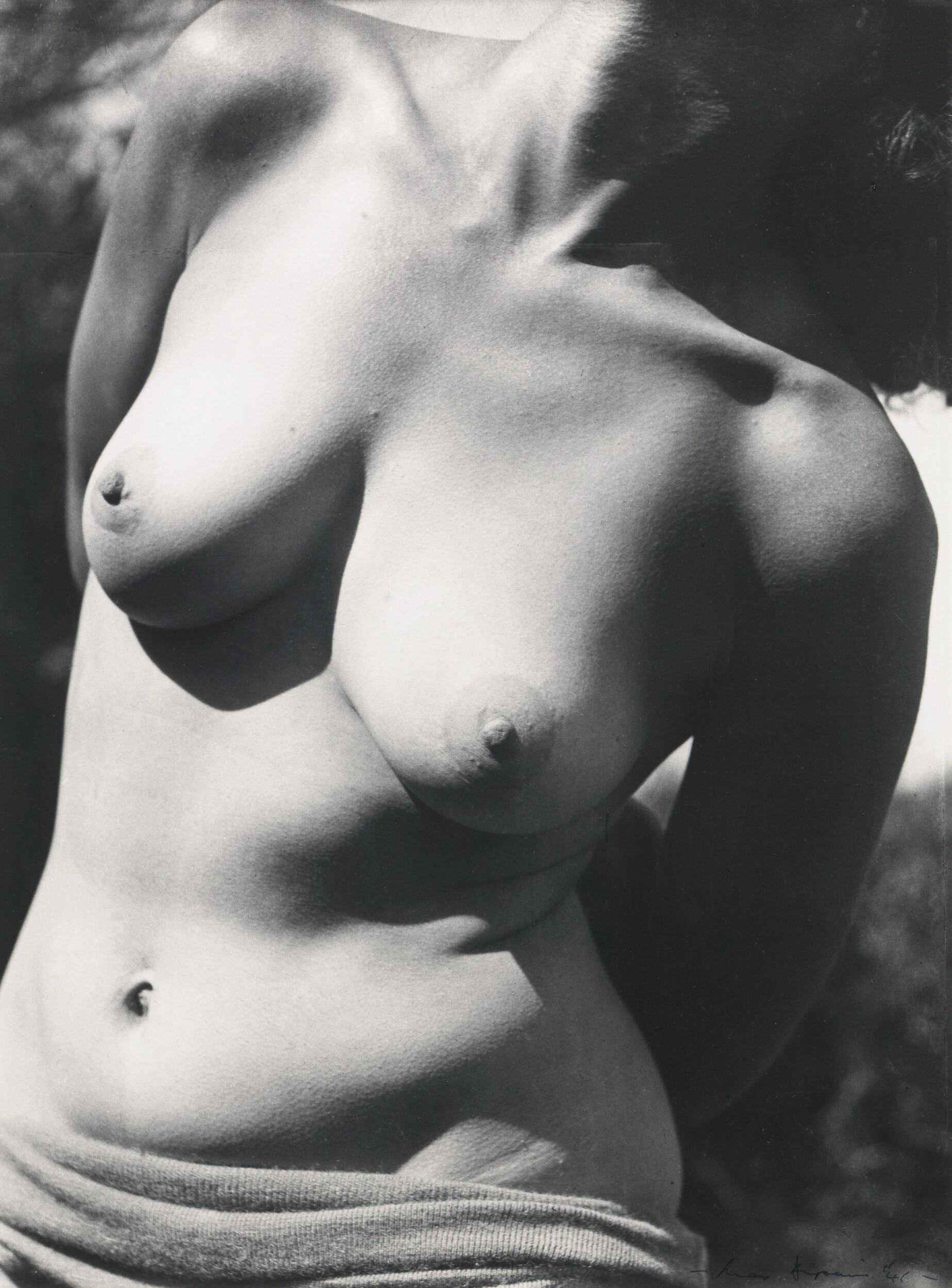

Man Ray, No title c.1930, printed 1982, gelatin silver photograph, 29.8 x 23 cm (image), 30.5 x 23.8 cm (sheet). Private Collection, Paris

In a small grouping that follows, a series of prints demonstrate the process of solarisation—a technique Man Ray and Lee Miller collaborated on in 1929, achieved by briefly switching on the darkroom light during exposure. The method introduces chance directly into the photographic process, the result hinging on the smallest variations: the amount of light exposure, and at what angle it strikes the paper. The artist cannot control these conditions precisely; instead, the accidental is, in Surrealist terms, both analogous to and a trigger for the unconscious. Four of the six prints in this section are by Dupain, who it seems first attempted the method around 1935, using shells, lilies, daffodils, and even an egg as subject matter. A vintage print of Hera Roberts (1935), which is solarised, and Homage to Man Ray (1937) make that debt explicit, revealing how emboldened Dupain was by Man Ray’s technical experiments. The exhibition includes Dupain’s Nude (1934), a reverse-printed nude, first published in The Home in April 1934, demonstrating that he was already testing modernist photographic effects independently. What Man Ray offered was not a model to mimic, but a kind of licence to push further. As the wall label tells us, Dupain “was less interested in the psychological and unconscious aspects of Surrealism than in Man Ray’s testing of photography’s limits,” and it was within those limits that he found his own clarity.

Installation view of Man Ray and Max Dupain, Heide Museum of Modern Art, 2025. Photo: Ruby Taylor

With any two-person juxtaposition, certain visual comparisons are inevitable. The V-shaped mirrored exhibition design layout almost insists on it, reflecting one artist against the other at staged intervals. What’s more interesting is how Dupain’s and Man Ray’s works are often intermingled rather than segregated. The curators resist the urge to compare them in an annulled, oppositional way. Because many of the photographs are hung in grids or loose clusters, there aren’t individual wall labels for each work. Instead, a single caption sits to the side, covering the group as a whole. This forces the viewer to dart back and forth to check who made what. Moving through the exhibition, a kind of confusion sets in; any sense of linear logic or chronology falls away, and I find myself mistaking certain nudes and even fashion photographs made by one for the other. A trio of studies of hands keeps me busy for longer than I expect. The hang keeps you looking, and it feels right.

In a room flanked by heavy velvet curtains, we find a space devoted to photograms, also known as “camera-less” photographs, made by placing objects directly on light-sensitive paper so that light itself becomes the subject. It is a technique that captivated Man Ray, who even coined the term “rayograph” for his own experiments. Just outside, a copy of his album Champs délicieux (1922) sits in a vitrine. Made during a year when Man Ray produced as many as one hundred rayographs, the album marks the culmination of a pursuit of this technique begun in December 1921. Examples from it hang in the adjoining room, rewarding close looking: the brightest forms are those shielded from exposure, while objects shift and overlap across multiple impressions. Identifiable everyday objects include matchsticks, a print roller, a razor, an egg grater, metal coils, springs, and a pipe. Other shapes appear more translucent and harder to place. In one by Dupain, a puddle of water catches the light, casting shadows that seem to hover on the surface of the print. In one of the largest rayographs by Man Ray, two eggs, an ashtray, a pair of paintbrushes, and what we assume to be the artist’s own hands are arranged in luminous play. You can even make out his fingernails and, mirroring your own, notice his wide palms and stocky fingers.

Installation view of Man Ray and Max Dupain, Heide Museum of Modern Art, 2025. Photo: Ruby Taylor

In this room, it quickly becomes apparent who truly mastered the technique. Man Ray’s works whirr with assurance; Dupain’s, by comparison, who trialled the technique, feel tentative, as if still figuring it out. But that ease of comparison is part of what makes this mode of display so effective: it allows you to see the unevenness, the process of trying, of finding form. Elsewhere in the exhibition, Dupain appears more sure-footed, his compositions sharper, and his sense of purpose more defined. The back of Olive Cotton in Little Nude (1938) and the paired back composition of No Title (Nude on the Beach) (1937) are exceptional examples.

Installation view of Man Ray and Max Dupain, Heide Museum of Modern Art, 2025. Photo: Ruby Taylor

With a show billed as a two-person exhibition between two men, it is hard not to be reminded of the perennial problem: what to do with the women. In a deep-rose-red-coloured side room titled Collaborators, our focus is redirected to Olive Cotton and Lee Miller, who are presented as both central and marginal figures, at once practitioners and subjects for Man Ray and Max Dupain. The wall colour itself feels pointedly gendered, as if to frame the women within a softer, separate space. The curators have rightfully acknowledged them, yet their inclusion sits uneasily. Miller’s presence makes sense: her work and career are deeply intertwined with Man Ray’s, both as model and collaborator, and her fashion and commercial photography speak directly back to the room devoted to this style on the opposite side of the exhibition (a highlight is a 1930s Chanel ad). All but one of Miller’s works shown here are modern digital prints from the Lee Miller Archives in Sussex, likely a matter of logistics and funding rather than curatorial choice. Cotton’s inclusion, however, is more of a stretch. While represented by twelve prints, including a single photogram paired with one by Dupain, her presence appears intended less to trace Man Ray’s influence than to widen the frame of Australian modernist experimentation. In truth, she was not influenced by Man Ray at all. Cotton, who disliked disarray and was drawn to order, seems to have found little affinity with the Surrealist experimentation the exhibition otherwise celebrates. While Cotton remains a somewhat elusive presence here, her inclusion still serves as a reminder that Dupain’s modernism was never formed in isolation.

Installation view of Man Ray and Max Dupain, Heide Museum of Modern Art, 2025. Photo: Ruby Taylor

Up close, the presence of vintage material and silver gelatin prints still holds its sway. While some of the exhibition comprises posthumous prints—works reprinted in the 1970s and 1980s—there are more vintage photographs than expected, and they feel all the more precious for it. The exhibition’s loans are remarkable in today’s conditions of digital circulation, from an anonymous collection of Man Ray’s portraits of women from the 1920s, their soft focus and tonal richness, to Max Dupain’s vintage print of Torso in the Sun (1941), a nude of Olive Cotton rendered in luminous contrast. I kept returning to the sparkling surface of a 1933 print of the artist and model Meret Oppenheim, one of six portraits by Man Ray featured in the show, its metallic sheen glinting under the gallery lighting. The silvering-out process, in which the metal migrates to the surface, carries its own quiet sadness—a visible sign of degradation that can appear unexpectedly beautiful in raking light. It now seems to speak to the photograph’s material life, the silver literally coming forward as a reminder of photography’s own physicality. Elsewhere, there are traces of the artist’s hand: Dupain’s scrawled handwriting in green pen on his 1938 Surrealist Portrait of Miss Margery Nall and the framing marks visible on Man Ray’s Self Portrait (c. 1930). Then there are details that only reveal themselves in person, like the carefully drawn-on eyebrows of Kiki de Montparnasse in Kiki with African Mask (1926), a nuance that never quite translates in online reproduction.

Max Dupain, Torso in the sun 1941, gelatin silver photograph, 45.4 x 34.0 cm (image & sheet). Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide. Gift of the artist 1980

A list of associations rapidly begins to tally up in this exhibition: shared subject matter, close cropping, double exposures, mirrored distortions, photograms, solarisation, and so on. Yet there are also smaller, quieter correspondences. The tiniest work in the show, hung low and only a few centimetres across, is a beautiful portrait by Man Ray of Dora Maar (1936). Her hand curves across her forehead, partly obscuring her face, while a small porcelain hand rests at her throat, clasping itself like an uncanny stand-in. It’s a portrait that stages touch as both artifice and allure: a motif that reappears throughout Dupain’s work, where figurines and sculptural doubles are recurring props. In Discobolus and the Machine (1936), the feet of a broken figurine appear, both fragment and form. Made in the same year, these two photographs are not in conversation across time but in sync: products of a shared visual language emerging in parallel, a convergence of form, style, and iconography that points to similar preoccupations rather than influence. Discobolus and the Machine shares Man Ray’s fascination with reflection and repetition, even if it misses the spontaneity of his work, as seen in his portrait of André Breton reclining before a de Chirico painting. Dupain’s version, by contrast, feels more deliberate: a study in restraint rather than chance.

Max Dupain, Shattered Intimacy 1936, gelatin silver photograph, 36.7 x 45.4 cm (image), 38.4 x 45.8 cm (sheet), Art Gallery of New South Wales, purchased 1982

There’s been a quiet resurgence of interest in both artists that extends beyond Heide’s walls. Currently, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Man Ray: When Objects Dream revisits his paintings, sculptures, and rayographs, while earlier this year his 1924 photograph Le Viol d’Ingres fetched an extraordinary 12.4 million USD at auction. In Australia, the National Gallery is preparing a touring exhibition curiously pairing Max Dupain with Ansel Adams; the State Library of New South Wales will soon revisit Dupain in solo; and the NGA’s Olive Cotton and Her Contemporaries brings Cotton into conversation with international modernists such as Dora Maar and Lucia Moholy.

Man Ray, Le violon d’Ingres 1924, printed 1970, gelatin silver photograph, 38.5 x 30 cm (image). Private collection, Paris

It is tempting to read this simply as nostalgia for modernism, with its clean lines, optical games, and the myth of the “male photographer genius.” But this current wave of reappraisal suggests something more interesting. Dupain is not an Antipodean afterthought, and Man Ray’s singular, resolute photographs are here dispersed. The exhibition’s clusters, wall arrangements, and mirrored correspondences reveal a logic of exchange, even if the two never met. The work of both photographers appears not as baton-passing but as its own kind of dialogue.

Perhaps what we are seeing, then, is less a revival of modernism’s heroes than a recalibration of its geographies. These renewed pairings—Paris and Sydney, Man Ray and Dupain, Cotton and her international peers—show how the “modern” did not radiate outward from a single centre but circulated sideways, adapted, and refracted. To borrow again from Rex Butler and A.D.S. Donaldson, Australian art “is part of, and belongs to, the rest of the world.” In that sense, the spirit of a publication like Photographie—the avant-garde made portable, print made global—returns here in 2025. The revival is not just about rediscovering icons; it is about reimagining where and how modernisms emerged, where shared contexts rather than mere reception gave rise to distinct yet resonant articulations.