In March, I visited the Lowell Observatory — the astronomical research site where Pluto was first discovered — in Flagstaff, Arizona. I stood in line to squint through telescopes at Jupiter and the surface of the moon before the night turned cloudy and drove me inside the Astronomy Discovery Center museum. And like all museum visits, it ended in the gift shop.

This one was full of space paraphernalia, astronaut dolls, and NASA shirts. But what caught my eye were the dog plushies in silver spacesuits, name embroidered in blue on the front: Laika. She also came in the form of a backpack clip. It might have been cute if it weren’t so profoundly sad.

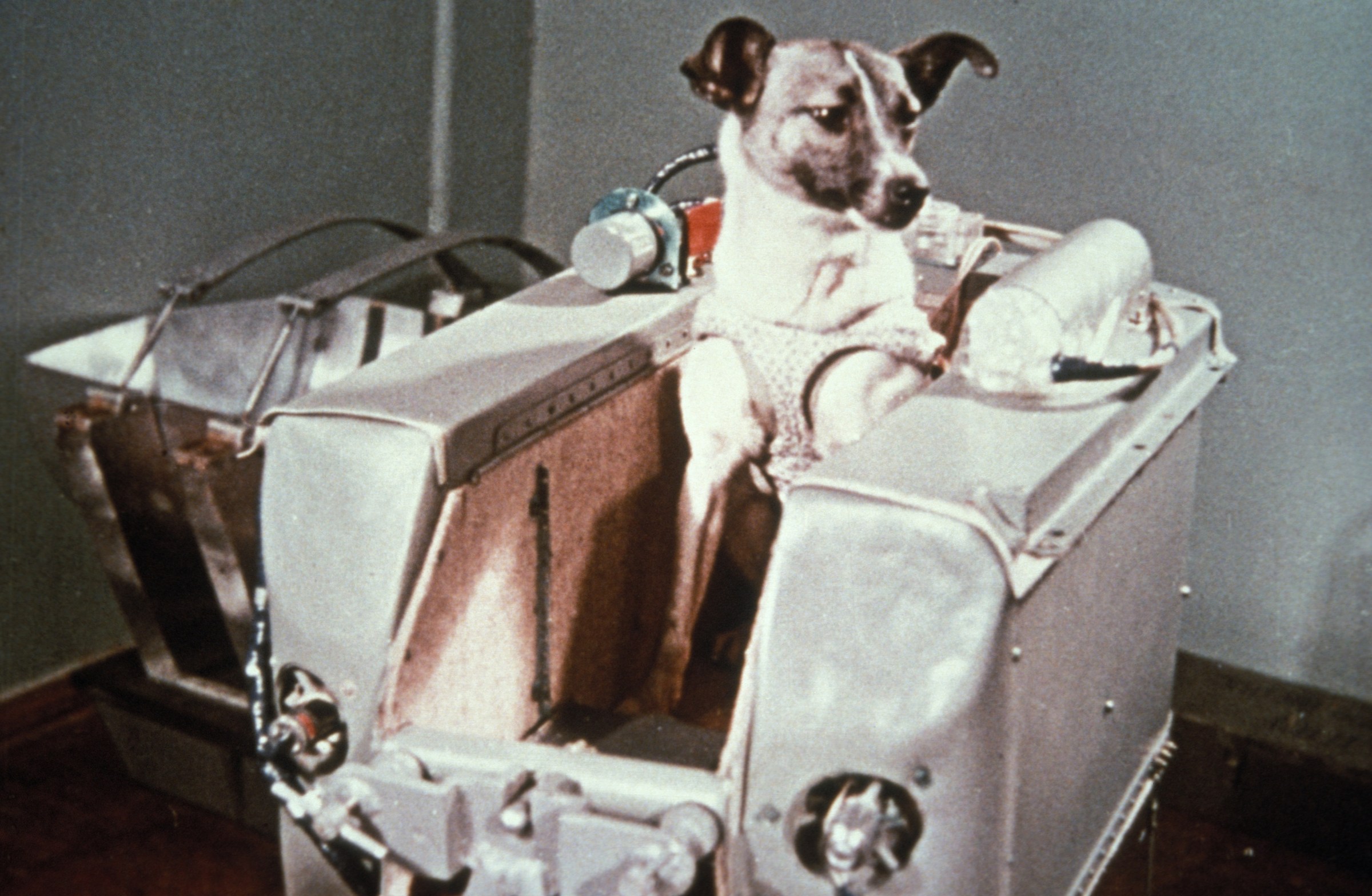

Because on November 3, 1957 — 68 years ago this week — Soviet researchers launched the real Laika, a small black-and-white terrier mix, into space aboard the Sputnik 2 spacecraft, where she became the first living thing to orbit the earth, proving that life could survive both launch and outer space conditions for extended periods of time. But the technology that would facilitate her safe re-entry did not exist yet, so there was never any hope that she would come back alive.

”After placing Laika in the container and before closing the hatch,” recalled Soviet engineer Yevgeniy Shabarov, “we kissed her nose and wished her bon voyage, knowing that she would not survive the flight.”

Laika in training for her mission. Sovfoto/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

The scientists intended for her to die painlessly after eating poisoned food after a week in orbit, but that’s not how the story turned out.

Soviet physicians had implanted sensors into Laika’s body before her doomed flight to track her vital signs while she was in space. During the launch, her breathing rate quadrupled and her heart rate tripled. She reached orbit alive, alone, and terrified, peering out through the window at the planet far below.

But then the life support capsule in her spacecraft malfunctioned, causing temperatures in the cramped cabin to spike to 104 degrees Fahrenheit. Somewhere between five and seven hours after launch, Laika died of hyperthermia and stress — overheating and panic. She had no way to understand what was happening to her.

American astronaut Scott Kelly has described space as smelling like burning metal. What must it smell like to a dog, with a nose at least 10,000 times more powerful than a human being’s?

Why did we send animals to outer space, and was it worth it?

Before humanity went to space, scientists feared that we could not survive extended periods of weightlessness. So we first experimented on animals as proof of concept. The Soviets preferred dogs, while Americans opted mostly for nonhuman primates like monkeys and chimpanzees, some of whom perished horribly.

“Recruited” into the Soviet spaceflight program from the streets of Moscow earlier in 1957, Laika was a well-behaved, 11-pound, 3-year-old stray. By all accounts, she was a very good girl. Vladimir Yazdovsky, the physician who had selected her for the mission, took her home to play with his children the night before her fatal mission. “I wanted to do something nice for her,” he later said. “She had so little time left to live.”

Before Laika, Soviet scientists had successfully (and non-fatally) launched other dogs into suborbital flights, which reach outer space but do not travel fast enough to orbit the earth. Laika wasn’t the last to be fatally sent into the cosmos, although most space dogs that succeeded her survived their missions, and mechanisms were put in place for their recovery. (Whether they came back dead or alive, though, the space dogs endured cruel training regimens that involved being confined in progressively smaller cages and subjected to deafening sounds to mimic launch conditions.) Her story has persisted in cultural memory as one of scientific progress, a sad but necessary part of the research that paved the way for human astronauts. She demonstrated that animals could survive launch conditions into space and successfully orbit the Earth, inspiring the US to kick its space program into high gear.

While Laika’s mission provided some of the first physiological data about the effects of space travel — and launching animals into space has provided us with knowledge that made it possible to more safely send humans into space — it’s also probable that this one-way mission, and others like it, weren’t worth the cost. Sputnik 2, along with Laika’s remains, disintegrated upon re-entering Earth’s atmosphere, so there was no body left to study.

The next year, a Polish scientific periodical decried the failure to bring Laika back to Earth alive as “regrettable” and “undoubtedly a great loss for science.” There was a sense among many, both now and then, that humanity used animals too liberally in space research.

After all, humans would have gone to space eventually, even if Laika was never launched with Sputnik 2. And it would have been possible to wait to send animals into orbit until we had the technology to recover them safely. Sputnik 2 had been a politically motivated rush job after the success of Sputnik 1 only a month before: Sergei Korolev, the father of the Soviet space program, had suggested sending a dog into orbit to surprise the Americans and mark the 40th anniversary of the October Revolution.

One of the scientists who worked on the Sputnik 2 program lived to regret it. “The more time passes, the more I’m sorry about it,” Oleg Gazenko told audiences at a 1998 press conference. “We shouldn’t have done it. We did not learn enough from the mission to justify the death of the dog.”

What we have — and haven’t — learned from Laika

Laika would go on to become one of the most celebrated dogs to ever live — Soviet allies issued commemorative Laika stamps, while the Soviet Union’s Russian successors honored her as a fallen cosmonaut. Popular representations of Laika tend to depict her as a happy dog astronaut, or as a proud martyr who chose to give up her life for a greater cause. She was turned into “an enduring symbol of sacrifice and human achievement,” as the space dog biographer Amy Nelson put it, inspiring monuments and so many musical tributes. A vegan lifestyle magazine (founded on the idea that sending her to space was a tragic mistake) and an animation studio bear her name.

But aside from some incredibly sad songs, little is said about what spaceflight was like for Laika and the many other animals sent to their deaths for space research. None of them understood what space was, nor did they have any choice in making the ultimate sacrifice for expanding humanity’s knowledge of the cosmos.

Laika stamps issued by Romania. Photo 12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Laika’s true cause of death by overheating was not publicly revealed until 2002. The Soviets feared it would spark opposition to its space program, and instead kept up the fiction that her end had been heroic and painless, the valiant sacrifice of a canine cosmonaut.

If you’ve ever loved and lost a dog, it’s impossible not to compare their life and death to Laika’s. My childhood dog, Muppet, passed away late last year. He was almost 15, very sick, and spent his last day eating treats. My parents held him as he was put to sleep. But Laika died young and healthy, alone, confused, and without any comfort.

Humans no longer send dogs and non-human primates to space — why would we, when we have willing human astronauts? — but animal experimentation in space research continues. Zebrafish, tardigrades, worms, flies, frogs, and rodents are still sent up to the International Space Station, where we use them to examine the effects of space radiation and microgravity on living tissue, model different diseases, and study reproduction in space, a prerequisite for a self-sustaining human settlement off of our planet.

It’s hard to muster up as much empathy for flies and worms as for our mammalian cousins, and tardigrades seem to adapt to life in orbit well enough. But it’s safe to say that mice deserve better than routine euthanization after they return to earth.

Humans tend to value our curiosity above animal life, using animals as instruments to achieve our own ends. Sometimes we gain from this tremendously, but the animals always lose out. While it’s unequivocally true that animal research in space can make the space environment safer for humans, there are competing incentives at play in weighing the potential benefits of space settlement against the very real cost to animals. This is a hard problem, and not one there are easy answers to.

But here’s some good news: Although humans still experiment on dogs here on Earth, that practice is on its way out. And new approaches to reduce animal testing show promise both on and off our planet. Organoids — miniature 3D organs grown from stem cells — even grow better in space than on the surface of the Earth. So maybe one day soon, space research could help facilitate the end of animal testing.

You’ve read 1 article in the last month

Here at Vox, we’re unwavering in our commitment to covering the issues that matter most to you — threats to democracy, immigration, reproductive rights, the environment, and the rising polarization across this country.

Our mission is to provide clear, accessible journalism that empowers you to stay informed and engaged in shaping our world. By becoming a Vox Member, you directly strengthen our ability to deliver in-depth, independent reporting that drives meaningful change.

We rely on readers like you — join us.

Swati Sharma

Vox Editor-in-Chief