Since the Paris Agreement was signed a decade ago, the projected global temperature increase by the end of the century has declined from a range of 3.7 degrees to 4.8 degrees, to one of 2.6 degrees to 2.8 degrees.

Alongside that profound practical achievement, the treaty’s goals of holding the temperature increase to an agreed target and doing so by reducing emissions to net zero by 2050 have become accepted as the norm around the world. Mechanisms such as having signatories declare new and more ambitious targets every five years are now in place.

The first cycle has just concluded, in which Australia committed to a 2035 emission reduction target of cutting greenhouse pollution by 62 to 70 per cent of 2005 levels.

Not all countries have complied, but almost 75 per cent of global emissions are now covered.

This year, for the first time in history, the amount of energy the world derived from renewables overtook the amount generated by coal.

Analysis by the energy think tank Ember shows that in the first half of 2025, the combined growth of solar and wind power exceeded global demand growth by 109 per cent. Solar alone met 83 per cent of the increases as coal generation slipped 0.6 per cent.

“We are seeing the first signs of a crucial turning point,” said Małgorzata Wiatros-Motyka, senior electricity analyst with Ember, when the analysis was published.

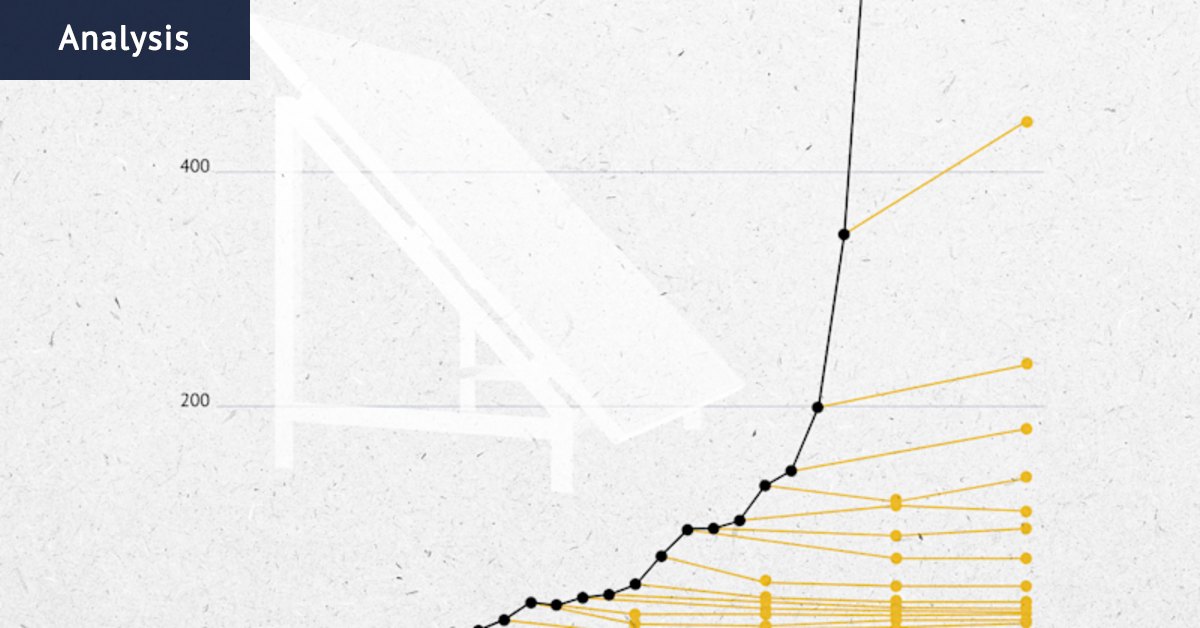

This brings us back to that hopeful chart. The startling explosion of renewables, particularly solar, can be mostly attributed to China’s production, deployment and export of solar cells, which has driven down the price of the technology around the world, and in turn its uptake around the world.

Discussing this energy revolution last year, analyst Michael Liebreich explained to The Economist that in 2004, it took the world a whole year to install a gigawatt of solar-power capacity; in 2010, it took a month; in 2016, a week.

“In 2023 there were single days which saw a gigawatt of installation worldwide,” The Economist reported. “Over the course of 2024 analysts at BloombergNEF, a data outfit, expect to see 520-655gw of capacity installed.”

This is profoundly good news, not just for the benefits to world’s climate – and its economy – of abundant cheap and clean energy, but because it demonstrates that multilateral efforts to tackle climate change can not only have an impact but already are having an impact.

But it is not all good news.

Addressing world leaders before the formal negotiations, United Nations secretary-general António Guterres said bluntly that our actions to date remained too little and too late to avert catastrophe.

“The hard truth is that we have failed to ensure we remain below 1.5 degrees,” he said. “After decades of denial and delay, science now tells us that a temporary overshoot beyond the 1.5 limit – starting at the latest in the early 2030s – is inevitable.”

With concerted effort, the world might arrest the warming and drive it down again before the end of the century, but the human cost would be terrible, Gutteres said.

“Even a temporary overshoot will unleash far greater destruction and costs for every nation,” he said. “It could push ecosystems past catastrophic and irreversible tipping points, expose billions to unliveable conditions, and amplify threats to peace and security.

“Every fraction of a degree higher means more hunger, more displacement, more economic hardship, and more lives and ecosystems lost.”

According to a UN report on the gap between the necessary reductions and the world’s current trajectory which was published last month, global emissions are expected to fall by about 10 per cent by 2035, compared with 1990 levels. This is the first decline ever forecast by the organisation, but it falls well short of the 60 per cent decline necessary to put us on a target to stabilise warming in line with Paris targets.

Part of the reason for the gap is what the economics writer Ed Conway has called the “evil twin” of the hopeful chart above, which shows that just as the IEA keeps failing to forecast the speed at which China deployed renewables, it also failed to predict how much new coal it would chew up.

Finally, it appears that renewables have won, and are not only supplying new energy demand, but displacing coal. Further, China’s export of renewables technology is beginning to spur a green revolution in other emerging mega-markets, such as Pakistan and India, where coal’s share of new energy demand is in rapid decline.

Loading

This year’s talks will proceed without the diplomatic machine of the United States, which under recent Democratic administrations has served to drive the agenda forward. Instead, the Trump administration is at work unwinding renewables subsidies and tax breaks in the US and driving a fossil fuel expansion.

Australia’s delegation will arrive having so far failed to secure the right to co-host a COP in Australia with its Pacific neighbours due to the determination of Turkey to remain in the race despite broad support for Australia’s bid.

This will not just distract Australia’s Climate Change and Energy Minister Chris Bowen from the task at hand; it may set a precedent that could destabilise future talks at a time when climate leaders are urging for co-operation to accelerate the process.

Addressing world leaders last week in Rio, the UN’s chief climate official, Simon Stiell, said the energy revolution had begun, but needed full global co-operation.

“Paris is not working fast enough,” he said. “We have the direction, but we don’t have the speed.”

Get to the heart of what’s happening with climate change and the environment. Sign up for our fortnightly Environment newsletter.