At the time, pokey, dark homes dominated Australia’s landscape. So Grounds did something radical: he designed the 1937 Ramsay House, which Lee credits as “probably the first example of Australian modernism”.

Loading

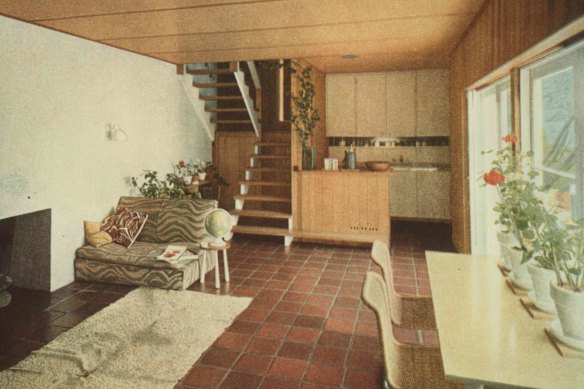

“You can see Roy starts moving away from the white box to the low gabled roof … and starts to incorporate aspects of Australian culture, lifestyle and climate,” Lee explains.

The Ramsay House is also built from local materials such as timber, a feature of mid-century Australian design.

It is also the debut of large, north-facing windows, and an open-plan internal design that “allows the flexibility of communication between kitchen, dining and living space,” Lee adds.

Grounds’ 1937 Ramsay House is the first example of Australian modernism. Credit: Herbert Fishwick

The Ramsay House was also one of the first homes to acknowledge Australia’s landform. There is also a sense of optimism, an appetite for something new and radical following the depression in the 1930s and war in the 1940s.

Loading

“In the late ’40s, you have this kind of opening up and optimism: the sun shining after all of that, servicemen coming home. There’s a baby boom; there’s a sense of possibility that things could be different,” Rory Hyde, an associate professor in architecture at the University of Melbourne, says.

“And into that social and political moment comes a design movement that tries to give shape to it and to express those values.”

While Grounds is widely considered the first, even most radical architect of this movement, he has many disciples, influencing “a whole generation of architects,” Lee says.

Mid-century modern for the masses

Among them was Robin Boyd, whose debut into the public arena was spearheaded by The Age and the Institute of Architects in 1946 to launch the Small Homes Service: a world-first initiative that offered Melburnians access to drawings for affordable dwellings, able to be constructed by small builders or home owners, but designed by architects to be liveable.

The Age hired Boyd to write a weekly column to “encourage people to think about housing, their needs, and to respond to the houses he was designing in the Small Homes Service,” Lee says.

The service was popular. It was responsible for 40 per cent of new homes in Melbourne during its peak, and inspired architects including Kevin Borland to integrate his designs into the rugged bush setting of suburbs like Eltham.

The Rice House, designed and constructed by Borland in the early 50s for the Rice family, features a pair of shell-like concrete structures on a hilltop acre with a regenerated bush garden.

The Rice House in Eltham has been faithfully restored and is up for sale. Credit: Fletchers Real Estate

The home at 69 Ryans Road, Eltham, first went up for sale in 2016, and since restored by current owners with help from Heritage Victoria.

It is for sale again, with a price guide of $1.35 million.

Fletchers real estate agent Aaron McDonald says the unique property has attracted downsizers and young families willing to live in it as is.

“It’s not everyone’s cup of tea … [but] the current owners have respectfully restored the Rice House with modern conveniences,” he says.

It is also a quintessential example of mid-century design’s focus on seamless indoor-outdoor integration, a philosophy Grounds took even further when designing his family home in Toorak in 1954.

Rou Grounds’ Hill Street house in Toorak is another example of mid-century architecture’s fluid approach to indoor-outdoor designs. Credit: Alex Coppel

The first of five units known as the Hill Street Flats, 1/24 Hill Street is renowned for its use of geometry – a circular courtyard, open to the sky and featuring two batches of bamboo, in the centre of a square-building footprint.

Grounds, like other mid-century architects, relied on “the innate qualities of the materials to provide the interest inside the house – he was not trying to apply decorative features,” Lee says.

The home was listed with a price guide of $2.3 million to $2.5 million this spring and recently sold.

Around the same time, another architect, Peter McIntyre and his wife Dione, designed the innovative Butterfly House in Kew.

Using a structural system developed by engineer Bill Irwin, they built the home – an experimental design featuring bold colours and a spiral staircase that curls up the central frame of the home, connecting the three levels of the house – among the treetops, above flood-prone land.

Mid-century architect Peter McIntyre’s Butterfly House was an experimental design featuring bold colours and an innovative engineering system. Credit: McItyre Foundation

“The mid-century architects believed in clean design, in the sun shining through the window,” says Hyde. “They were celebrating and encouraging people to take a risk on a new type of design, when they might have been used to those very brick, very solid, small-windowed buildings.”

Robin Boyd’s Walsh Street house in South Yarra, designed for his family in 1957, is one of Melbourne’s best-known mid-century residences. It not only serves as a model for his design theories, but also embodies the design principles Boyd championed in his book, The Australian Ugliness, with an introspective layout and two structures surrounding a central courtyard.

Walsh Street House by Melbourne architect Robin Boyd.Credit: John Gollings

Architect David Godsell’s house, named after him, was his first residential project and experimented with new methods and ideologies, influenced by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, says Fiona Austin, founder of Beaumaris Modern.

“Wright’s houses were designed to complement the landscape and climate of America. The Godsell house successfully incorporates many of these principles,” she says.

Architect David Godsell’s house was influenced by American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, and his philosophy that houses should complement the landscape and climate of where they are built. Credit: Fiona Austin

The Grimwade House, which only opened to the public last week, is another example of “an ingenious adaptation that understands its Australian context”, Lee says.

“It’s a very comfortable and relaxed house, which was the intention of the architect,” he adds. “It’s not precious, highly structured or organised.”

One of Victoria’s most celebrated modern houses, the Grimwade House, designed by architects David McGlashan and Neil Everist in 1960 to 1962, recently opened to the public for the first time. Credit: Simon Schluter

Mid-century’s influence today

Some of its intrinsic elements – simple designs, access to light and adaptation to Australia’s climates – influence architects today.

Architect Adriana Hanna, who updated architect Alistair Knox’ 1960’s modernist home, the Fisher House, in 2019 to suit a family of four, says some people consider mid-century homes “dark and brown and ugly,” but designers love their simplicity.

“The solar orientation, natural ventilation, access to daylight in all the rooms and a connection to the Australian landscape are really resonating with designers,” she says.

The Fisher House in Warrandyte. Credit: Sean Fennessy

Hanna says Nightingale Housing is an example of mid-century design principles influencing modern housing. The not-for-profit, which builds simple, sustainable homes, considers community and a relationship to the landscape.

One of the Nightingale apartment blocks in Brunswick.Credit: Derek Swalwell

Jeremy McLeod, founder of architecture firm Breathe (which developed the concept of Nightingale), says Australia’s current situation is not so different from post-war scarcity that gave way to mid-century design.

“We have a climate crisis, a cost-of-living crisis and a housing crisis. We also have limited resources, and we need to use them wisely,” he says.

“The times we are in, and the challenges Housing Australia and Homes Victoria have to deliver housing at this particular time will demand design rigour that will be similar to that we saw post World War Two.”