A mini wind farm in New South Wales is repowering with new two megawatt (MW) turbines, and hopes to give the old ones a second life elsewhere in Australia.

But in a wearisome repeat of the relentless campaigns against wind projects, even this tiny, two turbine wind farm has come under fire as opponents spread incorrect information against it.

Owner Windfarm 1, a private company which owns the land, is planning to decommission the 24-year-old Vestas V47 660 kilowatt (kW) turbines in Hampton, a town about 26km south of Lithgow, and replace them with a model that is the smallest available today, at 2 MW.

The old turbines, which are listed as a tourist attraction on the Tourism Lithgow website, have a tip height of 73.5m and were finished in 2001 on a budget of just $2.5 million.

The proposed new machines are Vestas V80-2.0 MW models, which have a tip height of 120m – still relatively small by current standards – with a total capital cost expected to come in at $12.71 million.

But Windfarm 1 is doing its upgrade in a very different era, and the development application is full of reminders that the wind farm is now a piece of local heritage in its own right.

“It is acknowledged that [Lithgow] Council does not favour large expanses of land being covered with solar energy or wind farms where there is significant cumulative impact,” the application says.

“The two proposed wind farms are replacement of two existing turbines which have been operational on the subject site for over twenty years,” the development application says.

“[The] two new turbines are replacements of the existing two turbines which have been operational for over 20 years with no known such adverse impacts [on grazing, farming, residential, tourism, business and forestry practices.”

There is one area where it is having to lean on that heritage factor: the proximity to houses and roads.

In 2000, when construction started, putting a turbine or two just 330 metres from the nearest house or 300m from the nearest intersection wasn’t the big deal it is today.

Today, NSW guidelines are based on a merit assessment of individual projects but that turbines should be more than two times the tip height from a road.

The proponent has shifted the turbines as far back from the road as possible, and says it doesn’t expect people who live near the two machines to be too bothered by the replacement turbines.

More fake news

The repowering proposal is attracting opposition and, as is increasingly being found to be the case with anti-renewables campaigns, it’s rife with false and misleading information.

A campaign on Facebook has come out strongly against the proposal, supported by Nationals MP Paul Toole who said on the platform in October that “over 100 locals” attended an information meeting.

According to the Australian Bureau of Statistics census figures, that would have been all of the people living in Hampton, but it has to be said that many renewable projects attract opposition mostly from long distance critics.

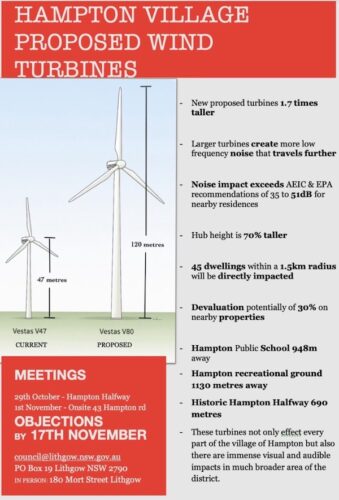

A grossly misleading graphic (see below) compares the hub height of the existing turbines, with the tip height of the new turbine.

The leaflet advertising the campaign against the repowering project. Image: Facebook

The accompanying text uses a level of rounding that no maths teacher would allow to claim the new turbines will be “1.7 times taller”.

The leaflet makes an evidence-free claim of nearby properties being devalued by “potentially 30 per cent”, when every piece of research for more than a decade disproves that this actually happens over the long term.

It cites a noise level peak of 51 decibels (dB) that the development application explicitly says won’t be reached: peak noise levels for the two closest residences are predicted to jump by 2 dB to 42 dB and 43 dB.

The application says the new turbines “may result in a reduction in noise levels at nearest receivers”, given it’ll be new machinery.

It’s also unclear just how many of the locals are upset.

“There will be additional consultation to assess the impacts on recipients of the changed turbines, however preliminary discussions with key residents suggest a level of comfort with the proposed changes,” the wind farm owner says in its application.

A 600t crane and two weeks

Getting rid of the turbines will take about two weeks, with a 600 tonne crane brought in to dismantle the blades, nacelles and tower. The baseplates and cables will then be removed and covered over with topsoil.

The plan is to either rehome the turbines or recycle them.

“It should be noted that while the metal components of the existing facilities can readily be recycled, at the moment commercial opportunities for blade recycling are quite limited,” the application says.

“Contact has been made with the firm Acciona, who are pioneering recycling of turbine blades through their “Turbine Made” initiative. They have advised that they have successfully trialled the technology and are currently seeking development partners.”

If you would like to join more than 28,000 others and get the latest clean energy news delivered straight to your inbox, for free, please click here to subscribe to our free daily newsletter.

Rachel Williamson is a science and business journalist, who focuses on climate change-related health and environmental issues.