For years, scientists have debated whether Mars could host liquid water beneath its icy surface. Recent radar findings, particularly from the Mars Advanced Radar for Subsurface and Ionosphere Sounding (MARSIS), suggested the possibility of liquid water in the southern ice cap. However, new data from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter’s SHARAD radar have cast doubt on this theory. In an article published in Geophysical Research Letters, Gareth Morgan and his team dive into these conflicting results, offering fresh insights into what might really lie beneath Mars’ icy exterior.

Mars: A Frozen Desert with a Hidden Potential?

Mars, once home to flowing rivers and vast bodies of water, has been transformed by billions of years of harsh conditions. Today, its surface is cold and dry, and liquid water seems like an unlikely prospect. However, previous radar readings, including those from MARSIS, indicated a different story. Beneath the southern ice cap, a 20-kilometer-wide section showed unusual radar reflections, leading scientists to speculate that liquid water could exist under the ice. This discovery seemed promising—until SHARAD’s recent findings, which painted a different picture.

Researchers had long suspected that liquid water might still exist in pockets on Mars, particularly below its ice caps where conditions could be more stable than at the planet’s surface. However, for liquid water to remain stable beneath the ice, factors like heat from volcanic activity or high concentrations of salts would be necessary to keep the water from freezing. This understanding was the basis for much of the excitement surrounding the MARSIS data, but new findings from SHARAD suggest that the situation may be more complicated than anticipated.

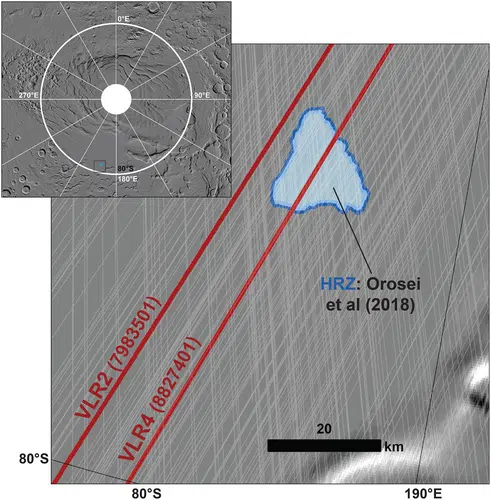

High Reflectivity Zone (HRZ) region of the South Polar Layered Deposits (SPLD) showing SHARAD coverage at roll angles less than 30° (white lines) and the ground tracks of the two SHARAD Very Large Roll observations (red lines). Inset shows the location of the HRZ within the SPLD. Background is MOLA hillshade.

High Reflectivity Zone (HRZ) region of the South Polar Layered Deposits (SPLD) showing SHARAD coverage at roll angles less than 30° (white lines) and the ground tracks of the two SHARAD Very Large Roll observations (red lines). Inset shows the location of the HRZ within the SPLD. Background is MOLA hillshade.

(Geophysical Research Letters)

MARSIS vs. SHARAD: Two Radars, Two Different Views

Gareth Morgan and colleagues, in their article published in Geophysical Research Letters, tackled the stark contrast between the radar signals captured by MARSIS and SHARAD. The MARSIS radar, operating at lower frequencies, detected strong reflections from the ice cap, which suggested the presence of liquid water beneath. This discovery seemed to offer hope that Mars might harbor more than just frozen water—potentially even a habitable environment.

However, SHARAD operates at higher frequencies and has a more precise ability to penetrate the Martian surface. Until recently, its signals couldn’t reach deep enough to probe beneath the ice, but a new maneuver, called a “very large roll” (VLR), allowed the team to access deeper layers. When this new technique was applied, SHARAD detected a much weaker signal at the same location that MARSIS had flagged as a hotspot for liquid water.

While the MARSIS findings sparked excitement, SHARAD’s faint signal points to the possibility that the high-reflectivity zone might not be a sign of liquid water at all. The weak SHARAD signal suggests that there may be smooth, solid ground beneath the ice—something entirely different from the liquid water suggested by MARSIS.

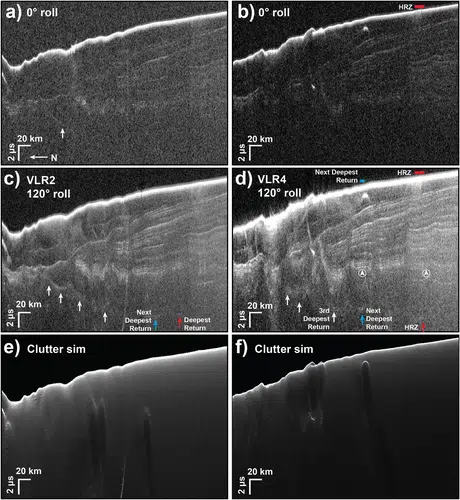

SHARAD data collected over the South Polar Layered Deposits in the vicinity of the High Reflectivity Zone. 0° roll radargrams colocated with the two very large roll (VLR) collects: (a): obs. 2244_01 and (b): obs. 36330_01. (c) 120° roll VLR2 radargram (obs. 79835_01). (d) 120° roll VLR4 radargram (obs. 88274_01). White arrows highlight the basal return as seen in each data set. The red arrows in panels (c, d) highlight the (faint) deepest basal returns within the VLR radargrams. The corresponding blue arrows show the location of the next deepest basal returns. The circled arrows in panel (d) highlight the internal reflectors considered for loss estimates. Absence of corresponding features in clutter simulations for the (e) VLR2 and (f) VLR4 observations supports a subsurface source.

SHARAD data collected over the South Polar Layered Deposits in the vicinity of the High Reflectivity Zone. 0° roll radargrams colocated with the two very large roll (VLR) collects: (a): obs. 2244_01 and (b): obs. 36330_01. (c) 120° roll VLR2 radargram (obs. 79835_01). (d) 120° roll VLR4 radargram (obs. 88274_01). White arrows highlight the basal return as seen in each data set. The red arrows in panels (c, d) highlight the (faint) deepest basal returns within the VLR radargrams. The corresponding blue arrows show the location of the next deepest basal returns. The circled arrows in panel (d) highlight the internal reflectors considered for loss estimates. Absence of corresponding features in clutter simulations for the (e) VLR2 and (f) VLR4 observations supports a subsurface source.

(Geophysical Research Letters)

Why the Discrepancy? Understanding the Radar Reflections

The key to understanding this discrepancy lies in the nature of radar reflections. MARSIS, with its lower-frequency radar, is better suited to penetrate the ice and reveal large-scale features beneath the surface. Its stronger signal reflections from the high-reflectivity zone led scientists to hypothesize that liquid water might be lurking there.

On the other hand, SHARAD, using higher frequencies, provides greater resolution and precision. While it previously couldn’t penetrate as deep, the new VLR technique enhanced its signal strength and allowed it to reach the base of the ice where MARSIS had picked up the strong reflections. Yet, the signal it received was weak, suggesting that the area might be composed of smooth ground or other materials rather than liquid water.

There are alternative explanations for the radar reflections that both instruments have detected. Layers of carbon dioxide ice, which behaves differently from water ice, could cause stronger radar reflections, or salty ice and clay could also be responsible for this signal. These materials would still create a strong enough reflection to suggest something beneath the surface, but not necessarily liquid water.