“I hate being called a cyclist. Because in my head I was never a cyclist. I was a runner who took up cycling as a side gig. Anyway, I try not to call myself a runner anymore. I’m just a person who does as much sport in the mountains as possible.”

Emma Pooley is not easily pigeonholed.

During a decade-long stint in the professional peloton, Pooley established herself as one of the best climbers and time triallists of her generation. But it wasn’t even supposed to happen.

Back in 2002, a stress fracture in her right foot necessitated a break from her first love, running, and Pooley turned to cycling as an alternative, albeit temporary, “stress release” from university work, courtesy of a borrowed bike with an uncomfortable saddle.

Just five-and-a-half years after embarking on that temporary, “unwilling detour” into cycling, Pooley was stood on an Olympic podium, a silver medallist in the time trial at the 2008 Beijing Games. The climber from Norwich also played a crucial part in Nicole Cooke’s groundbreaking Olympic-Worlds road race double that same year.

A pro contract with Cervélo soon followed, and so did the victories: the Trofeo Alfredo Binda (twice), Flèche Wallonne, the GP Montréal (with a staggering 110km solo raid), the Tour de l’Aude, multiple British titles, and the Grande Boucle (the much-diminished descendent of the women’s Tour de France).

.jpg) Emma Pooley wins stage six of the 2014 Giro d’Italia (credit: Giro Rosa)

Emma Pooley wins stage six of the 2014 Giro d’Italia (credit: Giro Rosa)

There were also four stage victories at the Giro d’Italia, then the most prestigious of women’s cycling’s stage races, and two overall second places, both times to the imperious Marianne Vos. And in 2010, Pooley secured the biggest victory of her career, winning the rainbow jersey in the time trial in Geelong. Comfortable in the mountains and on her TT bike, Pooley was also capable of flitting between leadership roles and domestique duty depending on the race.

But the 43-year-old’s CV doesn’t end there. There’s also been four duathlon world titles, an Everesting record, marathon and triathlon successes, a Swiss championship in long-distance trail running, 11th at the uphill running worlds, a Brompton world championships win, and forays into bouldering, ultra-cycling, bikepacking, and cross-country skiing.

Oh, and a University Challenge appearance, a PhD, and a founding role, alongside Marianne Vos, in Le Tour Entier, the ultimately successful campaign to reintroduce the Tour de France to the women’s calendar. So, it’s fair to say Emma Pooley is far from just a ‘cyclist’.

“Obviously, I raced for a while and that was great. It was a really cool thing to get to do. And I feel super lucky for all the chances I had.

“But more than that, I’ve just spent a lot of my time in my life doing sport and being a bit obsessed with it. Partly for the racing, but also I just love doing it. I love training,” Pooley tells the road.cc Podcast from her home outside Zurich.

Now, however, she points out that most of her bike rides come courtesy of a heavy steel machine with flat pedals and panniers, which she uses to commute to work in the Swiss city, where she works as a geotechnical engineer. And she’s keen to embrace new sporting challenges, even if she’s, in her own words, “shit” at them.

“I made a conscious decision a few years ago about what am I going to do with my sporting side of me, which is really important. I’m definitely not going to win a bike race again, and I’m not going to get much faster at running,” she says.

“How do I carry on being happy with the sport I do? How I can I make it stay a meaningful part of my life, without just being whingy the whole time: ‘I’m getting old and I’m so slow, poor me’.

“So I do bouldering and in the winter I do ski touring and a bit of cross-country skiing. I’m shit at them. I’m really terrible at bouldering – and it’s okay. It’s fun being shit at bouldering.”

When she’s not “having a nap on the mat” while staring up at a rock wall, Pooley has also found the time to become a published author. But unlike most pro cycling memoirs (or ‘chamoirs’, as book reviewer Feargal McKay memorably dubbed them), this isn’t your standard ‘Bike Races According to Emma’ fare.

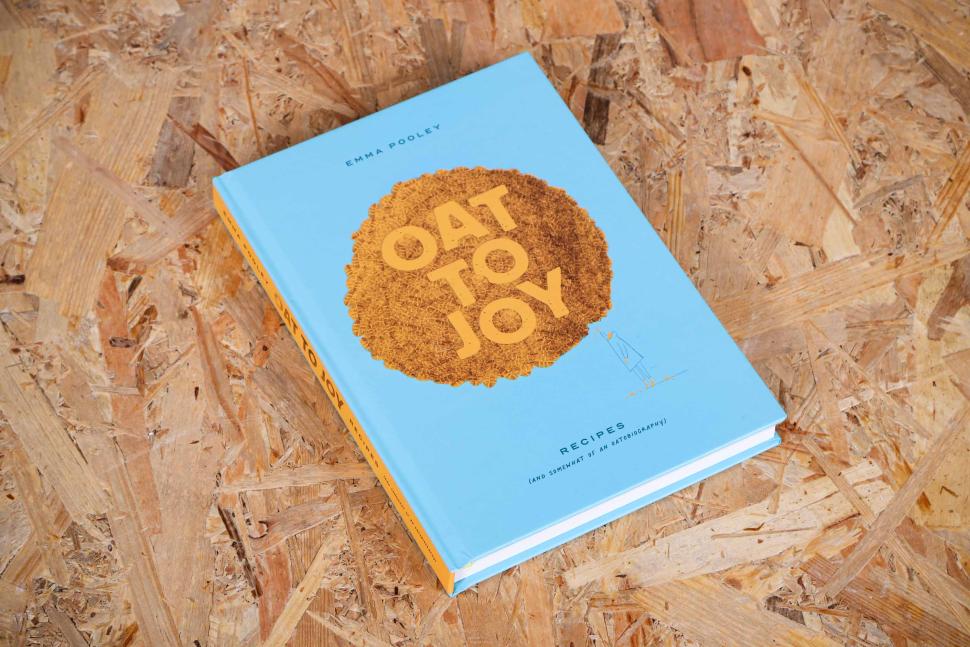

2025 Oat To Joy by Emma Pooley.jpg (credit: road.cc)

2025 Oat To Joy by Emma Pooley.jpg (credit: road.cc)

Instead, Oat to Joy is partly a collection of around 40 recipes for a range of snacks, based, naturally, on the humble oat and designed for people with active lifestyles and as an antidote of sorts to the typical highly processed sports ‘fuel’ on offer.

But the second half of Pooley’s book also sees her reflect on 17 key moments from her life and career, as well as themes surrounding gender and doping, often centred, again, on food.

> Review: Oat To Joy by Emma Pooley

“I love food,” she says. “I’ve been wanting to write recipes and put them together in a book for over 10 years. But I thought I should put some stories with it, basically to make it more interesting to people and give it a bit of a different angle.

“I was just going to write like short anecdotes about the time we had pizza at the end of the Giro or the crepes at the end of the Tour de Bretagne, and then I realised, wow, this is weird, I remember exactly what I ate after a bike race in 2008.

“I’d write some stories about some of the funny stuff that I ate along the way, and then they evolved from silly anecdotes to some of them turning into almost mini-articles. And it took me ages!”

“Nobody asked Froome’s rivals if they thought he was making them look fat”

The publication of Oat to Joy and Pooley’s food-centric tales earlier this summer coincided with the eruption of the so-called ‘weight debate’ in women’s cycling, following Tour de France Femmes winner Pauline Ferrand-Prévot’s admission that her weight loss prior to the race, which saw her become the Tour’s first home champion for over three decades, was “not 100 per cent healthy”.

Pauline Ferrand-Prévot wins stage nine of the 2025 Tour de France Femmes (credit: ASO/Thomas Maheux)

Pauline Ferrand-Prévot wins stage nine of the 2025 Tour de France Femmes (credit: ASO/Thomas Maheux)

Those comments sparked weeks of debate on social media, criticism from her rivals (Marlen Reusser claimed that Ferrand-Prévot’s weight loss “puts pressure on all of us”), and countless think pieces in the cycling presses. And, Pooley says, blown entirely out of proportion, a reflection she believes of cycling’s archaic approach to both gender and weight.

“I think it’s interesting that it came up in the women’s sport in a critical way, the angle taken by the reporting was very much, ‘oh look, she’s lost weight, let’s get the other riders to criticise her for it’,” Pooley points out.

“And I’ve never heard that happen in men’s cycling. I don’t remember when Froome won the Tour, reporters going up to his rivals and asking, ‘oh, do you think he’s making you look fat?’

“It’s worth bearing in mind that it was handled differently than it would have been in the men’s sport. And I am wary of thing being handled differently. After all, weight is a performance factor.”

Emma Pooley, road race, 2016 Olympics, Rio (credit: Alex Whitehead/SWpix.com)

Emma Pooley, road race, 2016 Olympics, Rio (credit: Alex Whitehead/SWpix.com)

However, while she is critical of the media response to the Tour de France Femmes’ weight debate, she acknowledges that the peloton – and cycling in general – is still struggling to shake off its unhealthy relationship with diet, in a world where riders weighed their chicken, went around pinching rivals’ waists at the start of the season, and where ‘skinny’ is all too often equated with ‘fast’.

And it’s something she admits she struggled with herself, both during her career and after leaving cycling.

“I ride a lot with clubs, and there are always these throwaway comments like, ‘I should lose weight’ or ‘I’ve earned a pizza’. And I’m thinking you don’t have to earn a pizza!” she says.

“That equating of having to do a certain amount to earn a treat, and that treat being the food you wouldn’t let yourself have otherwise, or ‘yesterday I ate too many calories so I have to ride an extra hour’ – that’s the kind of thing I used to do. So I recognise it, and it’s not a healthy relationship with food.

“The environment when I was racing was pretty unhealthy when it came to assuming skinny was better. And I was predisposed to have worries about it, having come from running. I would say I was pretty healthy, but I did worry about it. Especially because I was a climber and I always thought I’d be even better if I was thinner. But now I think, no way. If I was skinnier I’d have lost power, and in the years when I was thinner I got sick a lot.

“I had a bit of a problem with it for a while, and at some point I realised, during a big training block in Australia when I was staying with family and riding a lot, I realised the more I ate the faster I was, and I was getting stronger every week.

“So I went, ‘ah, maybe this whole starving yourself this is not good!’ After that, my mindset changed – not always successfully, though. It is hard in that environment. I was being compared to climbers and racing against people who had really obvious eating and dietary problems, and I always felt really fat.

“But mostly I was like, no, I’m going to eat what I felt was right. It’s not difficult to work it out, and I was going to eat as much as possible. But eating disorders never fully leave you.”

Emma Pooley, 2016 British national time trial championship, Stockton-upon-Tees (credit: Simon Wilkinson/SWpix.com)

Emma Pooley, 2016 British national time trial championship, Stockton-upon-Tees (credit: Simon Wilkinson/SWpix.com)

Pooley’s very personal approach to food and healthiness didn’t always endear her to some of cycling’s more old-school figures, howver. There was the time, recounted in Oat to Joy, when a sports director scolded her after the GP Montréal, in front of all her teammates, for drinking a hot chocolate.

‘It sets a bad example to the girls who are trying to lose weight,’ he shouted. Pooley had just won the race with a 110km solo attack.

“I was like, I probably burned 5,000 calories today. I could eat whatever the fuck I like. And hot chocolate’s not bad for you. Just because it tastes of chocolate doesn’t mean it’s bad for you. He told you to put extra olive oil on your pasta, but you shouldn’t have anything that tastes of chocolate.

“He was an idiot. So I had a bit of a fight with him. He wasn’t the only idiot, there were plenty of other idiots – and there were some very good people too.

“But it was quite fun taking a stand against some of the idiots in the sport, I had some DSs who were just fuckwits about food.”

“It was everything I ever dreamed of”

Pooley’s predisposition to challenging her sport’s ‘idiots’, she acknowledges, earned her a reputation, alongside GB teammates Nicole Cooke and the late Sharon Laws, for being ‘difficult’. A troublemaker.

That ‘difficult’ reputation was solidified during her battle to redress cycling’s gender imbalance. In 2013, Pooley became one of the co-founders, alongside fellow riders Marianne Vos, Kathryn Bertine, and triathlete and four-time Ironman world champion Chrissie Wellington, of Le Tour Entier.

The campaign group was set up to support the growth of women’s cycling and help establish a proper women’s Tour de France, a goal partially achieved at first through the one-day La Course race (its inaugural editions held on the not very Pooley-friendly cobbles of the Champs-Élysées) and then fully in 2022, when ASO resurrected the Tour de France Femmes.

Emma Pooley, 2014 Women’s Tour (credit: Alex Broadway/SWpix.com)

Emma Pooley, 2014 Women’s Tour (credit: Alex Broadway/SWpix.com)

“At some point I realised that your job as an athlete isn’t actually winning races, it’s – and this will sound corny – to inspire people to ride bikes or run, depending on what your sport is,” says Pooley, a past winner of the Grande Boucle, by definition a descendent of the women’s Tour of the 1980s, but which by 2009 had long lost its lustre, prestige, and all-important name recognition.

“Because I remember when I was a kid watching Paula Radcliffe in the marathon or Kelly Holmes winning double gold on the track and crying with like emotion and being so inspired to go out and run.

“And I realised that if there’s anything useful I could do in the sport, it would be to have that kind of effect on young people. And it doesn’t have to be that women inspire girls and men inspire boys and they’re totally separate – but there is a bit of, ‘you have to see it to be it’. And where the fuck was women’s racing on TV when I was a kid?”

While Pooley humbly stresses that her own role in progressing women’s cycling is relatively minor, she is happy that the sport is currently on the “right track”, thanks in part to the ongoing work of The Cyclists’ Alliance, led by her old teammate Iris Slappendel.

“I see way more women riding and I hear lots of stories about how much they love watching the racing and the fact the women racing now are heroes,” she says.

“There’s a lot that goes on behind the scenes to gradually raise the level of conditions for riders, which feeds back into the quality of the racing and the quality of the teams and the environments that we race in. And just it being a less miserable experience – because it was pretty miserable for a lot of people when I was racing.”

Pauline Ferrand-Prévot wins stage nine of the 2025 Tour de France Femmes (credit: A.S.O./Pauline Ballet)

The success of the Tour de France Femmes even inspired Pooley this summer to venture to the Col de Joux Plane, the first time she’d ever watched any iteration of cycling’s biggest race from the roadside.

“I was like, wow, there’s really a lot of people,” she says. “It was amazing. I was really emotional in a weird way. I shed a tear, it was beautiful to watch. And the highlight was watching Marianne ride by. It was everything I ever dreamed of.”

But over a decade ago, when she was in the trenches with Vos fighting for a women’s Tour de France, the crowds and spectacle of the Joux Plane seemed lightyears away.

“It was so exhausting and it was so much work,” Pooley says of her time with Le Tour Entier. “And it felt largely, not even thankless, it felt like I really got people’s backs up and I felt really criticised a lot of the time.

“Then I was on the UCI committee for a year and that was also just really frustrating. So I was like, fuck sports politics, I’m getting out.”

Emma Pooley, time trial, 2016 Olympics, Rio (credit: Alex Whitehead/SWpix.com)

Emma Pooley, time trial, 2016 Olympics, Rio (credit: Alex Whitehead/SWpix.com)

Pooley’s foray into cycling politics also had ramifications on the sporting side of things. In Oat to Joy, she claims that one female team manager, trying to encourage Pooley to sign for her team, told her that, if a deal was done, they would contractually ban her from publicly commenting on women’s cycling. Bad publicity, apparently.

“And that was a female DS,” Pooley says now. “A female DS who subsequently worked in media, commentating on the likes of La Course.

“So she basically made a living off the work of people like me kind of campaigning, improving the profile of the sport.

“Anyway, that pissed me off.”

Pooley’s cycling career may have been punctuated by different kinds of conflict – whether it was in the press, UCI conference rooms, or in the dining rooms of post-race hotels – but a decade on, it’s clear that she’s now at peace with her role in the sport, and how others view her.

Nicole Cooke and Emma Pooley show off their medals from the 2008 Olympics in Beijing (credit: Getty)

Nicole Cooke and Emma Pooley show off their medals from the 2008 Olympics in Beijing (credit: Getty)

“A person who is not accredited enough is Nicole Cooke, because she had to fight so hard for everything she won before 2008,” Pooley says.

“And because she was also before the era of it being on TV very much and because she stood up for herself, British Cycling didn’t love her. They also didn’t love me, interestingly.

“When I was writing the book and I was struggling with the chapter about the Tour de France, and basically like fighting people like Dave Brailsford and stuff, someone told me that enemies are a sign of a life well lived, that they’re a compliment.

“And I’m proud of the fact that Dave Brailsford doesn’t like me.”

For the moment, anyway, Pooley’s ‘enemies’ are confined to the terrible drivers she encounters on her commute to work in Zurich, as well as the MAMILs on their expensive road bikes desperately struggling to drop her on the hill home.

“Normally I get overtaken by people on very, very nice bikes with fancy kit – so I would like to rain more just I could try to keep with them and give them a total crisis of masculinity,” she laughs.

“My bike is steel, it’s got massive panniers on because I sometimes have to take my building site helmet and my orange suit and stuff, so I need lots of space and I might pack a lunch.

“So if I can keep with them for just five minutes, these poor guys, they’re just going to go home and cry and Google ‘performance enhancing drugs for the commute’.”

The lesson there? Never try to pigeonhole Emma Pooley.

The road.cc Podcast is available on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, and Amazon Music, and if you have an Alexa you can just tell it to play the road.cc Podcast. It’s also embedded further up the page, so you can just press play.