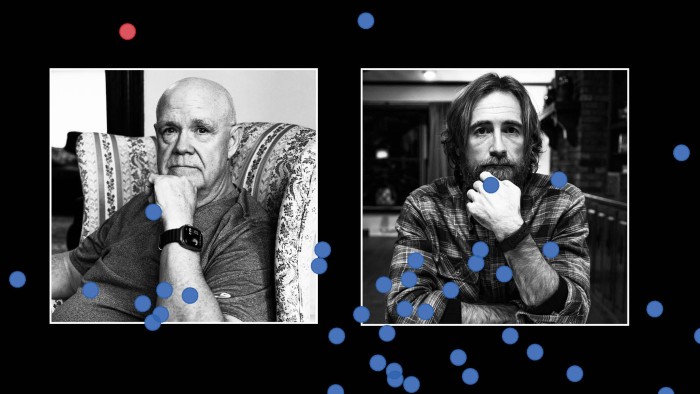

Mike Plante could hardly believe his eyes when he discovered how much his health insurance premiums will go up next year.

The 64-year-old public relations consultant is paying $400 a month. But this will jump to $1,965 — a nearly 400 per cent increase — if he renews his existing plan.

“Me and some 65,000 other West Virginians are about to be run off a cliff,” he said.

Plante is one of nearly 22mn Americans enrolled in health insurance under the Affordable Care Act — or Obamacare — who will see their premiums soar next year if their tax credits expire as expected on December 31.

“It’s a full-blown crisis,” said Mike Pushkin, chair of the West Virginian Democratic party. “Ours will be one of the states hardest hit by the failure of Congress and the Trump administration to extend these subsidies.”

The tussle over the ACA comes as President Donald Trump faces mounting pressure to ease prices for Americans, with affordability rising up the political agenda and looking set to dominate next year’s midterm elections.

“It’s going to become the central issue, because it’s something we all know and feel,” said Ellen Allen, head of West Virginians for Affordable Healthcare. “Congress is going to have to address it.”

Polls show Americans are increasingly worried about rising rents, grocery prices and healthcare costs, with anger over the cost of living reflected in the results of recent off-year elections in Virginia, New Jersey and New York City, when Democratic candidates swept the polls.

A Pew Research poll last month found 65 per cent were very concerned about the price of food and consumer goods and 61 per cent by the cost of housing.

US media earlier this month reported Trump was considering a new plan to bring down the cost of health insurance — though he is unlikely to propose extending the expiring ACA subsidies.

The issue of affordability is particularly acute in West Virginia, one of the poorest states in the country. Covenant House, a non-profit which runs a food pantry in Charleston, the capital, has had a big uptick in demand for its services in recent months.

Its chief executive Briana Martin said most of their clients were “working people struggling to put food on the table”.

Briana Martin, chief executive of Covenant House, said: ‘The cost of living is so high, and wages are stagnant’ © Guy Chazan/FT

Briana Martin, chief executive of Covenant House, said: ‘The cost of living is so high, and wages are stagnant’ © Guy Chazan/FT

“Individuals have to choose between paying rent, paying for food or utilities or paying for a doctor,” Martin said. “The cost of living is so high, and wages are stagnant.”

The dispute over healthcare costs is wrapped up in the complex history of Obamacare. Initially, only those earning up to 400 per cent of the federal poverty level (FPL) — currently $128,600 a year for a family of four — qualified for the ACA tax credits.

Joe Biden’s administration lifted that cap in 2021, and since then, the subsidies have been available to millions more middle-class Americans.

In West Virginia, a historic number of people enrolled in health insurance as a result of the change. “Our ACA marketplace this year had about 67,000 enrollees, up from 23,000 in 2022,” said Rhonda Rogombé of the West Virginia Centre on Budget and Policy.

But Republicans want to let the subsidies lapse, saying only those truly in need should receive help from the state. They also argue the system is rife with fraud and abuse.

However, experts fear people will opt out of health insurance altogether if the tax credits expire. Allen said the uninsured rate of 5.9 per cent in West Virginia will “creep back up to 18-20 per cent over the next couple of years” if the subsidies lapse.

“We already have some of the most abysmal infant mortality rates in the country, with some areas at third-world levels,” she said. “This is going to make it that much worse.”

With a population that is generally poorer, older and sicker than in other states, West Virginia has some of the highest per capita health costs — and some of the most expensive insurance — in the country.

The average monthly premium on the ACA marketplace was $1,172 a person in the state this year, nearly double the national average, according to Louise Norris, an analyst at healthinsurance.org, a consumer information website.

But those payments will become much higher if no action is taken to extend the tax credits. A 55-year-old West Virginian earning $63,000 a year who paid $18 a month for the cheapest insurance plan this year will have to fork out $1,041 a month for it next year, Norris said. “That’s the impact of the subsidy cliff,” she added.

Allen is herself a casualty. While she used to pay $487.50 a month, her new healthcare plan, with reduced coverage, has monthly premiums of $1,967.50.

People in their 50s and 60s are particularly badly hit. But younger West Virginians will also be affected.

Curtis Lovejoy, 37, of Pineville, deep in the Appalachian mountains, said the insurance he receives via the ACA marketplace will cost $360 more a year next year, even though he has just given up a second job that will reduce his income by $5,000 a year. If he still had that job his insurance would have cost him $1,548 more annually.

“It’s not much of an incentive to work more,” he said.

Curtis Lovejoy said of Republicans: ‘My fear is that their intention is just to get rid of Obamacare completely’ © Roger May/FT

Curtis Lovejoy said of Republicans: ‘My fear is that their intention is just to get rid of Obamacare completely’ © Roger May/FT

Lovejoy runs a number of assisted-living facilities in the area but is also a singer, with many of his self-penned songs addressing the cuts to health programmes, such as Medicaid, that were part of last summer’s sweeping spending plan that Trump called his “one big beautiful bill”.

“You’re in an area where people only survive because of Medicaid,” he said, citing research from the University of North Carolina which found seven rural hospitals in West Virginia were at risk of closure because of cuts in the taxpayer-funded programme for low-income and disabled Americans.

A spokesperson for the West Virginia Department of Health said the problems facing such facilities — declining populations, workforce shortages “and an outdated, volume-driven model that was already unsustainable” — predate Trump’s Medicaid cuts “by more than a decade”.

© Roger May/FT

© Roger May/FT

Meanwhile, the expiring subsidies continue to dominate discussions on Capitol Hill. The issue was a key factor in the record 43-day government shutdown earlier this month, with Democrats refusing to end the stalemate unless the tax credits were extended.

Ultimately, they relented after Senate Republicans agreed to hold a vote in mid-December on prolonging the support — though many of the party’s lawmakers remain firmly opposed to any rollover.

Republicans argue the tax credits were only ever intended as temporary pandemic relief and say the ACA is too expensive. Josh Holstein, chair of the West Virginia Republican party, said Obamacare was “cost[ing] the American taxpayer billions in subsidies”.

He said his party was working with the White House to reduce this burden by “giving money back to the American people to purchase their own health insurance at an affordable cost”.

Karoline Leavitt, White House press secretary, said Trump was “very focused on unveiling a healthcare proposal that will fix the system and bring down costs for consumers”. But “contrary to fake news reporting”, he was “not considering a straight two-year subsidy extension”.

Others remain sceptical of Republican plans. “My fear is that their intention is just to get rid of Obamacare completely,” Lovejoy said.

Back in Charleston, Plante is considering his options. One is to take out the cheapest medical policy available until he qualifies for Medicare, the state-backed health insurance programme for the over-65s.

“I’ll roll the dice and go for the catastrophic coverage,” he said. “And just drive very slowly for the next nine months.”

Additional reporting by Lauren Fedor in Washington.

Mike Plante points at health insurance plan details © Roger May/FT

Mike Plante points at health insurance plan details © Roger May/FT