December 2, 2025 — 12:55pm

Save

You have reached your maximum number of saved items.

Remove items from your saved list to add more.

Save this article for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them anytime.

Got it

The World Health Organisation (WHO) has urged governments to make GLP-1 medicines such as Ozempic more affordable, publishing new guidelines that endorse the high-profile drugs to treat obesity.

The WHO’s announcement came hours after Australia’s medicines regulator released a safety alert over the potential risk of suicidal thoughts and behaviours for people using the Glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1) medicines.

The WHO has endorsed GLP-1s for obesity treatment, but Australia has this week issued safety warnings.

The WHO has endorsed GLP-1s for obesity treatment, but Australia has this week issued safety warnings.

The WHO guidelines, published in the Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA), recommend that GLP-1 therapies be used for weight management in adults with obesity, alongside exercise, diet and regular counselling sessions.

But senior WHO advisors say, even if manufacturers were to rapidly ramp up production of the high-profile medicines, they would reach fewer than 10 per cent of the people who would benefit most from their weight-management effects by 2030.

The announcement is expected to bouy GLP-1 pharmaceutical manufacturers’ ambitions to list their medicines on Australia’s Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme (PBS) for use for obesity weight management.

No GLP-1 therapy is PBS-subsidised, meaning the medicines, costing hundreds of dollars per month, are not an option for many with obesity, which disproportionately affects low and middle-income individuals.

WHO director-general Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said medication alone would not solve the global health crisis, but “GLP-1 therapies can help millions overcome obesity and reduce its associated harms”.

“The availability of GLP-1 therapies should galvanise the global community to build a fair, integrated and sustainable obesity ecosystem,” WHO representatives wrote in JAMA.

“Even under the current highest projected scenario, production of GLP-1 therapies could only cover around 100 million people.”

Obesity directly affects more than 1 billion people worldwide. That is projected to rise to 2 billion by 2030, costing healthcare systems US$3 trillion per year. It is a leading cause of preventable deaths, with millions dying each year from obesity-related conditions.

Several countries subsidise GLP-1 therapies for weight management, including the UK, Canada, Germany and France.

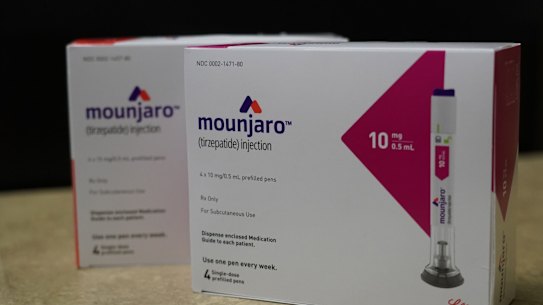

Wegovy (semaglutide), Saxenda (liraglutide) and Mounjaro (trizepatide) are approved for weight management in adults with obesity in Australia (defined as a body mass index of 30 or higher), but are not subsidised. Doctors can instead prescribe them via private scripts for this indication.

Wegovy costs $199 to $350 and Mounjaro (tirzepatide) costs $345 to $364 per month.

Ozempic (semaglutide) and Trulicity (dulaglutide) are PBS-subsidised but only for the treatment of hard-to-manage type 2 diabetes.

Novo Nordisk, maker of Ozempic and Wegovy, and Lilly, maker of Mounjaro, want these subsidies expanded to include treatment for obesity and heart disease.

WHO has endorsed GLP-1 therapies for obesity management.FLickr/Chemist 4U

WHO has endorsed GLP-1 therapies for obesity management.FLickr/Chemist 4U

In March, Federal Health Minister Mark Butler wrote to the Pharmaceutical Benefits Advisory Committee (PBAC) requesting advice on equitable access to these therapies for obesity treatment.

“When we get that advice, we’ll consider it carefully,” Butler said on Tuesday.

“This is obviously a class of drugs that [has] really taken the world by storm. They’re very significant new medicines, and we want to make sure we get access and affordability and equity right.”

An estimated half a million Australians use a GLP-1 medicine, 48 per cent of whom were prescribed the drugs on private scripts, according to University of Sydney research released in November that has not yet been peer-reviewed.

Doctors and diabetes patient advocates have raised concerns that too many people prescribed the drugs have no medical need for them.

The new guidelines bolster a major international shift from treating obesity as a lifestyle condition, which has tacitly enabled stigmatisation and blame, to recognising obesity as a chronic, relapsing disease that requires lifelong care.

Obesity rates in Australia have been rising for decades. More than one in four children and adolescents (26 per cent) and more than two in three adults (66 per cent) were living with overweight or obesity in 2022, AIHW data shows.

Spokespeople for Novo Nordisk and Lilly welcomed the WHO’s endorsement.

Dr Ana Svensson, vice president (clinical, medical and regulatory) at Novo Nordisk Oceania, said the company recently made its third submission to PBAC to secure a PBS listing for Wegovy.

“We will continue to work closely with the Australian government and relevant stakeholders to improve access to obesity treatments,” Svensson said.

A spokesperson for Lilly Australia suggested that future guidelines should reflect recent data showing its drug was superior for weight loss compared to semaglutide.

Joe Proietto, Professor Emeritus at the University of Melbourne and a former board member of the World Obesity Federation, said these medicines needed to be cheaper.

“Nearly everybody with obesity who loses weight regains it because of the biological effects of the hormones that regulate hunger … so these people then need to be on these medications for the rest of their lives,” said the endocrinologist, who has sat on medical advisory boards for liraglutide and semaglutide, and been involved in educational sessions for Novo Nordisk.

On Monday, the Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA) updated product warnings on all approved GLP-1 medicines, advising doctors to monitor patients for worsening or unusual changes in mood after reports of suicidal ideation and behaviour.

The regulator stressed there was insufficient evidence of a causal link.

The Morning Edition newsletter is our guide to the day’s most important and interesting stories, analysis and insights. Sign up here.

Save

You have reached your maximum number of saved items.

Remove items from your saved list to add more.

Most Viewed in NationalFrom our partners