Frida Kahlo’s 1940 painting “The Dream (The Bed)” is no ordinary work of art. And the recent auction where it fetched $54.66 million, making it the most expensive artwork by a woman ever sold at auction, proves it. Behind this representation, which, according to Sotheby’s, “encapsulates her lifelong preoccupation with mortality, physicality, and the emotional complexities of selfhood,” lies a story that describes the painting’s abrupt departure from Mexico, against the backdrop of a romantic disappointment.

Professor Luis-Martín Lozano, a historian of Mexican and Latin American art, explains in a video call with EL PAÍS that the artwork, which he describes as “a complex self-portrait,” left the country between the 1940s and 1950s, before the government decree in 1984 that declared Frida Kahlo’s complete works an Artistic Monument of the Nation and prohibited the export of her creations. Kahlo’s intention was to get rid of a gift she had painted for the American photographer Nickolas Muray, who had been her lover for 10 years and who, in 1939, announced to her that he was going to get married.

Those years were not easy for the artist. Having just arrived from Paris in 1939, Kahlo received devastating news. “Diego Rivera asked her for a divorce, and Frida was heartbroken because she didn’t understand why. They had an open relationship: she knew he was seeing many women; he, in turn, suspected she had lovers. It wasn’t a conventional relationship, but the point is that she had to make her own way and was prepared to do so,” explains Lozano. And she had reason to believe. She had just had a solo exhibition in New York where she had sold several works, the Louvre Museum had bought one of her paintings during her trip to the French capital, and, moreover, she had Nick. “He was a support, a man who loved her and asked for nothing in return,” the expert says, adding: “Sort of, because, in reality, Nick would have married Frida if she had had the strength to leave Diego.”

The news of Muray’s marriage caught Kahlo off guard, as she was about to finish “The Dream (The Bed),” a gift to thank him for his emotional and financial support over the years. “It’s a painting that deals with dreams, yes, but it also relates to that reality constructed in Frida Kahlo’s subconscious. What happens in that constructed reality? She has peace: she’s detached from the conflict of Rivera’s divorce, detached from the conflict of her illness and her pain, and she’s at peace when she’s with Nick, because she’s very happy with Nick Muray.” But that happiness crumbled with the announcement of the upcoming nuptials, so that painting, with its profound significance for her, had to go.

According to the art specialist, in 1939, the Mexican painter told the photographer that she had been forced to sell the work to the Misrachi Gallery in Mexico City due to an urgent need for money, but this was a lie: the letter is from 1939, while the canvas is dated 1940. “In other words, she hadn’t finished it when she wrote that fictitious letter to Nick,” says Lozano, who suggests that Kahlo didn’t want to give the painting to Muray because “he was going to get married and then he would no longer be the recipient of that message” of gratitude and affection with which she had created it. According to the art historian’s research, the Mexican artist continued to offer “The Dream (The Bed)” to her American collector friends for $400, even after she had led the photographer to believe she no longer had it.

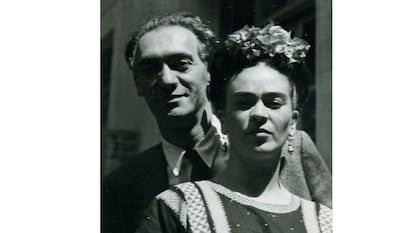

Nickolas Muray and Frida Kahlo in an undated photograph. Museo Frida Kahlo

Nickolas Muray and Frida Kahlo in an undated photograph. Museo Frida Kahlo

At some point, the painting was indeed exhibited for sale at the Misrachi Gallery, where it was acquired by a man named Luis de Hoyos. “We don’t know much about him. What we do know is that he came to Mexico and that he loved to fish,” Lozano remarks. And it is precisely De Hoyos who, in a way, explains the painting’s subsequent appearance outside the country. “When he died at his home in the United States, near New York, this was one of the paintings that were handed to Sotheby’s for auction,” the expert recounts. The rest is history. On May 9, 1980, the auction house sold it to a private buyer, and last November 20, the canvas was seen again after 45 years. A triumphant return that not only broke records but also confirms the attraction and fascination that the Mexican artist evokes worldwide.

Anna Di Stasi, director of Latin American Art at Sotheby’s, told EL PAÍS by phone that there is “a universal emotional state” in the artist’s paintings. “Frida Kahlo continues to have a very direct, very emotional connection across generations with different women, in different countries, and with different people,” she explained. For Di Stasi, “the reaction to her [Kahlo] is always emotional,” which goes hand in hand with the “fascination with her work and her life.” “It is one of her most surreal paintings, and it is understood that it is not just a portrait of her or her face; it is rather a portrait of her emotional state and her relationship with death. It is a highly psychoanalytic work.”

Di Stasi is not surprised by the success of “The Dream (The Bed).” “We’ve been building an art market primarily led by women for a decade now, many of them Latin American, who have found significant exposure for their artistic production at prices unthinkable 15 years ago,” she explains. The Sotheby’s Senior Vice President also believes that “these auctions establish an understanding that didn’t exist before about the region and the cultural heritage of a continent.” Furthermore, although she believes the art market fluctuates and “has preferences just like the design market,” for her, the important thing is to remain part of the conversation. Regarding the specific moment this record was reached, and what this says about the value placed on these types of works, she concludes: “I don’t know if we’re late to the party, but I imagine it’s better late than never.”

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition