‘AI safety’ has become a buzz-phrase in Silicon Valley, where tech companies use it to refer to artificial intelligence systems that reflect human values and protect human well-being. AI chatbots that encourage a person to commit crimes or acts of self-harm, for example, would fall outside this definition of AI safety.

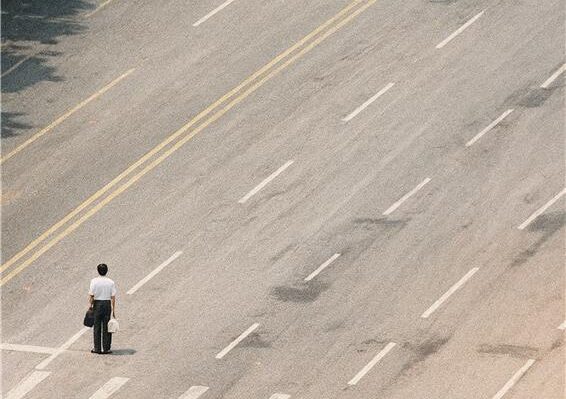

But missing from this definition is a focus on protecting human society from government abuse. Such abuse isn’t theoretical. The Chinese Communist Party is already using generative AI to deepen its repression. ASPI’s new report, The party’s AI: How China’s new AI systems are reshaping human rights, shows how the Chinese party-state has leveraged large-language models (LLMs) and generative AI to supercharge government surveillance and control.

China’s emerging AI architecture should serve as a cautionary example for democracies: it shows how quickly powerful models can be integrated into surveillance, censorship and social control when commercial incentives and state priorities align. To prevent this, open societies and democratic governments need to work together to adopt regulations that enshrine human rights and civil liberties as a key element of AI safety.

Our report, in partnership with the Human Rights Foundation, shows that AI now performs much of the work of online censorship in China and that Chinese LLMs censor not just politically sensitive text but also sensitive images. China’s censorship mandates have created robust market demand for censorship innovation and AI-enabled censorship tools, making it faster and cheaper than ever to filter and control what people say. Our research shows that the Chinese government is providing resources and incentives for researchers to develop advanced LLMs for minority languages such as Uyghur and Tibetan, for the explicit purpose of monitoring and controlling what people say online in those languages, both in China and beyond its borders.

Our report also finds that the Chinese government is deploying AI throughout the criminal justice pipeline through initiatives such as AI-enabled policing, mass surveillance, smart courts and smart prisons. Criminal suspects in China may now be identified and detained through the assistance of AI-enabled surveillance, prosecuted in courts where AI helps draft indictments and jail sentences, and incarcerated in prisons where AI surveillance systems monitor their facial expressions and emotions. This emerging AI pipeline strengthens the hand of prosecutors and further reduces transparency in a criminal justice system already heavily weighted towards convictions.

Our research also shows that the Chinese government has adopted a definition of AI safety that prioritises regime security above human wellbeing. As Chinese tech companies—operating in service to the party-state—grow more competitive internationally and as China aims to impose its AI norms and standards globally, China’s AI vision may spread—presenting a major challenge to the future of our world.

In response, democracies need to build AI ecosystems that actively resist the spread of authoritarian digital norms by making transparency, accountability and free expression core design principles rather than optional features. That means establishing procurement rules that exclude opaque or politically filtered models, mandating disclosure of any hidden moderation filters and protecting the researchers, journalists and auditors who test these systems from being sued, threatened, blocked or criminalised.

Democratic governments should coordinate to establish global standards that ban undisclosed political censorship, prioritise open and inspectable AI systems and restrict the export of surveillance and opinion-shaping technologies. They also need to disrupt the commercial incentives that fuel the censorship industry by requiring transparency and human-rights due diligence across AI supply chains, particularly targeting vendors selling sentiment-analysis and public opinion management tools.

The risk is not only to citizens of authoritarian countries. If left entirely to profit motives and market pressures, companies in open societies could pursue the same paths Chinese companies have taken. As our report shows, that would have serious negative implications for human rights and civil liberties.

Open societies need to avoid caving to the financial interests of AI companies and the billionaires who run them, who demand an underregulated environment to maximise their competitiveness and profit. Without a better balance between innovation and safety, democratic societies could easily innovate themselves into building AI ecosystems that centralise power, normalise online surveillance and erode the very democratic values they aim to support.

ASPI granted The Washington Post exclusive early access to this report. Read the article here.