The inequality is starkest in criminal justice — the poor are still disproportionately incarcerated, writes Gerry Georgatos.

THE LEGAL SYSTEM holds as its most sacred tenet the principle that all are equal before the law. Courts routinely assert this axiom, legislatures claim to legislate in accordance with it, and societies are reassured by the promise that justice is blind. Yet this assertion is not borne out in lived reality. Inequality before the law is not an exception; it is the norm, systemic and structural, cutting across class, race, gender, and economic capacity. To state plainly: it is not true that all are equal before the law.

The road to equality is equality; the road to justice is justice. If the law cannot be accessed by all equally – because of prohibitive costs, entrenched power imbalances, and systemic biases – then the legal system itself is compromised, if not decimated. This essay argues that the Australian justice system, like many others globally, has been captured by exorbitant legal costs and monopolised by those with wealth. This creates a reality where the poor are incarcerated at higher rates, the marginalised are silenced, and the wealthy manipulate the law to their advantage.

The myth of equality before the law

The idea that all are equal before the law is deeply embedded in legal culture. It has its origins in Enlightenment philosophy, constitutional frameworks, and declarations of rights. Yet even in its earliest expressions, the claim was aspirational rather than descriptive.

In reality, courts presume equality as a matter of form but operate amidst glaring inequalities of substance. Those who appear before the courts do so with vastly different resources, capacities, and vulnerabilities. The legal system’s failure lies not only in failing to acknowledge these disparities, but in perpetuating and profiting from them.

Consider the aphorism that “justice delayed is justice denied.” For those without means, justice is not merely delayed; it is denied altogether. Equality before the law, absent equal access to the law, is an illusion.

Wealth and the hijacking of justice

The greatest distortion of equality before the law is financial. Legal costs in Australia are notoriously exorbitant. Senior counsel command daily rates comparable to the annual income of many Australians. Large firms bill in six-minute increments, commodifying every moment of interaction. For ordinary people, litigation is not a viable pathway — it is financial ruin.

This creates a two-tiered system:

• For the wealthy, the law is a tool of protection, a weapon, and sometimes a shield against accountability.

• For the poor, the law is a threat, a site of dispossession, and a machinery of punishment.

The commodification of justice means that the law itself has been hijacked. Lawyers and firms extract obscene profits while access to remedies – be they civil, criminal, or administrative – remains closed to the majority. This is not merely a question of inefficiency; it is the saddest indictment of humanity. When wealth determines access to law, the system ceases to be just.

Incarceration and inequality

The inequality is starkest in criminal justice. The poor are disproportionately incarcerated. They lack resources for adequate defence, cannot afford bail, and are pressured into plea bargains. By contrast, individuals with financial resources can mount protracted defences, exploit procedural advantages, and sometimes evade conviction altogether.

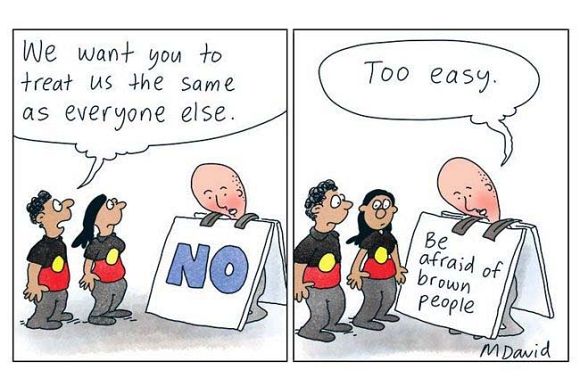

Consider the over-representation of First Peoples in custody. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples make up less than 4 per cent of the Australian population but constitute nearly one-third of the prison population. This is not merely a racial disparity but also a classist one, rooted in the legacy of colonisation, dispossession, and poverty.

Meanwhile, organised criminal networks – wealthy by illicit means – often evade justice through high-calibre legal representation. Thus, the system punishes the poor and protects the powerful.

Case studies in civil law

Defamation

Defamation in Australia is famously “the rich person’s tort.” High-profile politicians, business magnates, and celebrities weaponise defamation law to silence critics. The average citizen cannot afford to bring or defend such an action. As a result, reputational redress is reserved for the wealthy, while the poor remain defenceless against slander or coercion.

Probate and wills

Probate disputes are similarly skewed. When a will is contested, the costs of litigation can consume entire estates, leaving the wishes of the deceased subverted and heirs disinherited. Wealthier parties can protract proceedings until poorer relatives concede. The principle that the law will uphold the intentions of the deceased collapses under the weight of financial attrition.

Commercial litigation

In commercial law, multinational corporations dominate litigation through sheer financial power. Smaller entities – small businesses, unions, or individuals – are forced to settle on unfavourable terms or withdraw altogether. Litigation becomes not a means of determining justice, but a battleground of attrition where the deepest pockets win.

The classist and racist tirade

The injustice is not only racial or economic; it is both. The poorest quintiles of society—whether Indigenous or non-Indigenous—are excluded from genuine participation in the legal system. The top fifth of the income base, along with transnational corporations, dominate proceedings. The remaining four-fifths of society are financially outmatched, unable to “sit at the table” as equals.

This creates a classist tirade, compounding a racist one. First Peoples are doubly marginalised — by poverty and by systemic racism. Refugees and migrants experience similar inequities. Even among non-racial minorities, class stratification ensures that the poor are silenced.

Constitutional and statutory pathways

If equality before the law is to be more than rhetoric, constitutional and statutory interventions are required.

Constitutional possibilities

While the Australian Constitution lacks an express equality clause, purposive interpretations could be developed.

For example:

• Section 51(xxix) (External Affairs power): Used to incorporate international human rights treaties, including the ICCPR and ICESCR, which enshrine equality before the law.

• Implied principles: Just as the High Court has recognised implied freedoms (such as political communication), it could recognise an implied guarantee of substantive legal equality.

Statutory interventions

Parliament can legislate to make justice affordable:

• capping legal fees in certain matters;

• expanding legal aid funding dramatically;

• mandating pro bono quotas for large firms; and

• creating tribunals with simplified procedures to address probate, defamation, and minor criminal matters.

Case study: Industrial relations tribunals

The Fair Work Commission demonstrates that simplified statutory frameworks can resolve disputes affordably and accessibly. Expanding such models into civil and criminal contexts would democratise justice.

Restoring discursive justice

The law must rediscover its discursive functions: mediation, arbitration, negotiation, and amelioration. These processes, when affordable and accessible, reduce adversarial harm and produce durable outcomes. Yet when captured by profit motives, even Alternative Dispute Resolution (ADR) becomes prohibitively expensive.

Restoring discursive justice requires state support, community-based justice models, and traditional methods, particularly Indigenous practices such as yarning circles, which prioritise restoration over punishment.

Towards a better humanity

The law should not be a marketplace where obscene wealth buys justice. It should be a common good, a public trust. \

Reclaiming equality before the law requires systemic change:

• recognising that affordability is as central as principle;

• ensuring the marginalised have genuine access to remedies; and

• preventing corporations and the wealthy from monopolising outcomes.

This is not merely a legal reform but a moral imperative. For humanity to progress to its better self, law must be the domain where every individual, regardless of wealth, stands equal.

Conclusion

The road to equality is equality; the road to justice is justice. For too long, the claim that all are equal before the law has been a hollow promise. The Australian legal system, marred by obscene costs and structural inequities, systematically denies justice to the poor and marginalised while empowering the wealthy.

To transform this, we must look to constitutional interpretations, statutory reforms, and community-based justice. Case studies in defamation, probate, and criminal justice illustrate the urgency. Unless access is affordable, justice will remain a privilege of the few.

The greatest step forward for humanity is to reclaim the law as a site of true equality. This means dismantling financial barriers, addressing systemic biases, and affirming, not merely asserting, that all are indeed equal before the law.

Gerry Georgatos is a suicide prevention and poverty researcher with an experiential focus on social justice.

Support independent journalism Subscribe to IA.

Related Articles