Europe isn’t the only economic bloc pondering a response to the tide of Chinese exports. From Africa to Latin America and South-East Asia, alarm bells are ringing and protectionist sentiment is rising.

Loading

China’s exports to Africa have risen 26 per cent this year, while exports to South-East Asia are up 14 per cent and those to Latin America 7.1 per cent.

The remarkably rapid shift in the flows of China’s exports stems from Trump’s tariffs and their impact on the trade between China and the US, where China’s exports were 29 per cent lower last month than in November last year, and 19 per cent lower over the 11 months.

Some of the exports flowing to South-East Asia – as a bloc, imports from China are up about 24 per cent this year – may represent re-routing and then transshipment of goods to the US to take advantage of the discrepancy between the rates of US tariffs on China and those on exports from Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, the Philippines, Vietnam and Malaysia.

The average effective rate of tariffs on US imports from China is variously estimated at between about 32 per cent and 37 per cent, whereas the average rate on South-East Asian exports to the US is around 19 per cent. There’s an arbitrage opportunity in the differentiated rates.

The impact of China’s aggressive trade policies is magnified by the deficiencies within its domestic economy, which is plagued by weak demand, the continuing implosion in its property sector and industrial over-capacity. That’s reflected in the flat-lining of its imports.

Xi Jinping has steadfastly refused to do what most economists outside China, and some within, have been advocating for years – which is to attempt to significantly boost domestic consumption.

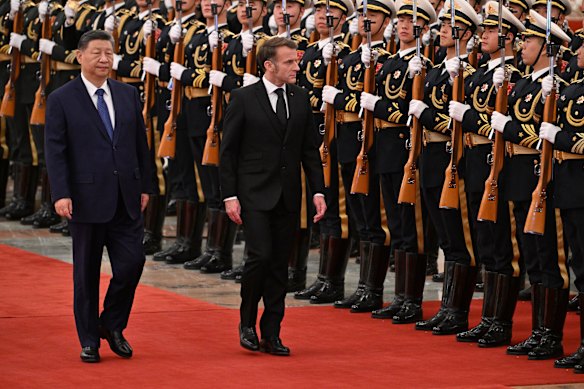

France’s President Emmanuel Macron with President Xi Jinping at his state visit to China last week. Credit: Getty Images

Despite the years of the property-crisis-induced domestic economic weakness, Beijing has only tinkered with measures to stimulate demand, instead maintaining its centrally directed and subsidised quest for global industrial dominance.

China’s exports are equivalent to about 0.9 per cent of global GDP and, in a world where global trade is growing at or just above 2 per cent, it is tearing market share in traded goods away from the rest of the world, while offering little in return as it pursues Xi’s strategy of growth via exports while achieving self-sufficiency in its home markets. Xi argues against protectionism abroad while effectively practising it at home.

By pursuing such a narrow and aggressive “beggar thy neighbour” policy, swamping other markets while closing its own, China is inviting a response from the trading partners it increasingly relies on for growth.

Xi Jinping has steadfastly refused to do what most economists outside China, and some within, have been advocating for years – which is to significantly boost domestic consumption.

Trump missed an opportunity by discarding the Biden administration’s targeted tariffs on China and igniting a trade war with almost the entire non-US world.

Had he enlisted the EU and others whose economies were being threatened by China’s exports, it would have forced China to confront the imbalances in its own economy instead of, together with the US, exacerbating those within the global economy.

Trump also misdiagnosed America’s problem, which isn’t the trade deficits it has run for the past 50 years but a lack of savings relative to its investment and consumption. He should have focused on America’s domestic economic settings – where he expanded those imbalances during his first term and is doing it again in his second – rather than looking elsewhere for someone to blame.

In any event, Trump’s tariffs have up-ended and are re-making global trade routes and China’s centrally planned and heavily subsidised strategic manufacturing sectors are pouring exports increasingly above domestic demand into international markets.

Loading

The effect of those settings is being amplified by a managed currency that is loosely pegged to a US dollar whose value has slumped almost 10 per cent since Trump regained office in January. In effect, that has produced a 13 per cent devaluation of the yuan against the euro, making China’s exports to Europe even more competitive.

No wonder the Europeans are anxious and talking about trying to stem the tide through their own protectionist measures. They’re talking about tariffs, quotas and minimum local content levels for their industries, and exchanging technology transfers and investment from China for access to their markets.

Xi has been advocating efforts to reduce over-capacity and endless price wars within China’s markets, but the objective seems to be about making Chinese industry and its exporters more efficient, less wasteful of national capital and to try to head off incipient deflation than to produce a more balanced economy.

Effectively, China has doubled down on an export-driven economic strategy, despite Trump’s tariffs.

Should the rest of the world decide that in a global trade environment fragmented by this combination of US protectionism and Chinese mercantilism, it will have fewer imports and higher domestic prices to protect jobs and a manufacturing future – Xi’s policies could backfire on China.

The Market Recap newsletter is a wrap of the day’s trading. Get it each weekday afternoon.