Everyone talks about digitalisation, yet only a few take real action. The cycling industry isn’t short on data. It’s short on structure, integration and ownership. We continue to operate as if it were 1999: emails, spreadsheets and guesswork. While other sectors connect systems, we keep flying blind. Digitalisation isn’t innovation. It’s overdue hygiene.

This article is part of the Brixen Bike Papers – a 41 Publishing initiative from our 2025 Think Tank in Brixen, created with the goal of building a better bike world.

A series of essays diving into the uncomfortable truths, hidden opportunities, and real changes our industry needs. Click here for the overview of all released stories.

The Brixen World Bike Papers – The Lack of Digitalisation

1. The myth of the missing data

The bike industry loves to repeat that it lacks data. It is one of those sentences that keeps circulating in keynotes, panels, round tables and crisis meetings. But it’s not true. Data exists. It is generated every second. Production data, warranty data, sales data, order intake, stock levels, forecast accuracy, shipment delays, lead times, purchase patterns, model rotations, and regional differences. There is no shortage of information.

The real problem is that the data is fragmented, disconnected and often unused. It sits in ERP systems that don’t communicate with each other, in Excel files that change ownership ten times before being outdated, in emails sent as attachments to people who left the company three months ago, in supplier portals nobody logs into, and in dashboards that look impressive but explain very little.

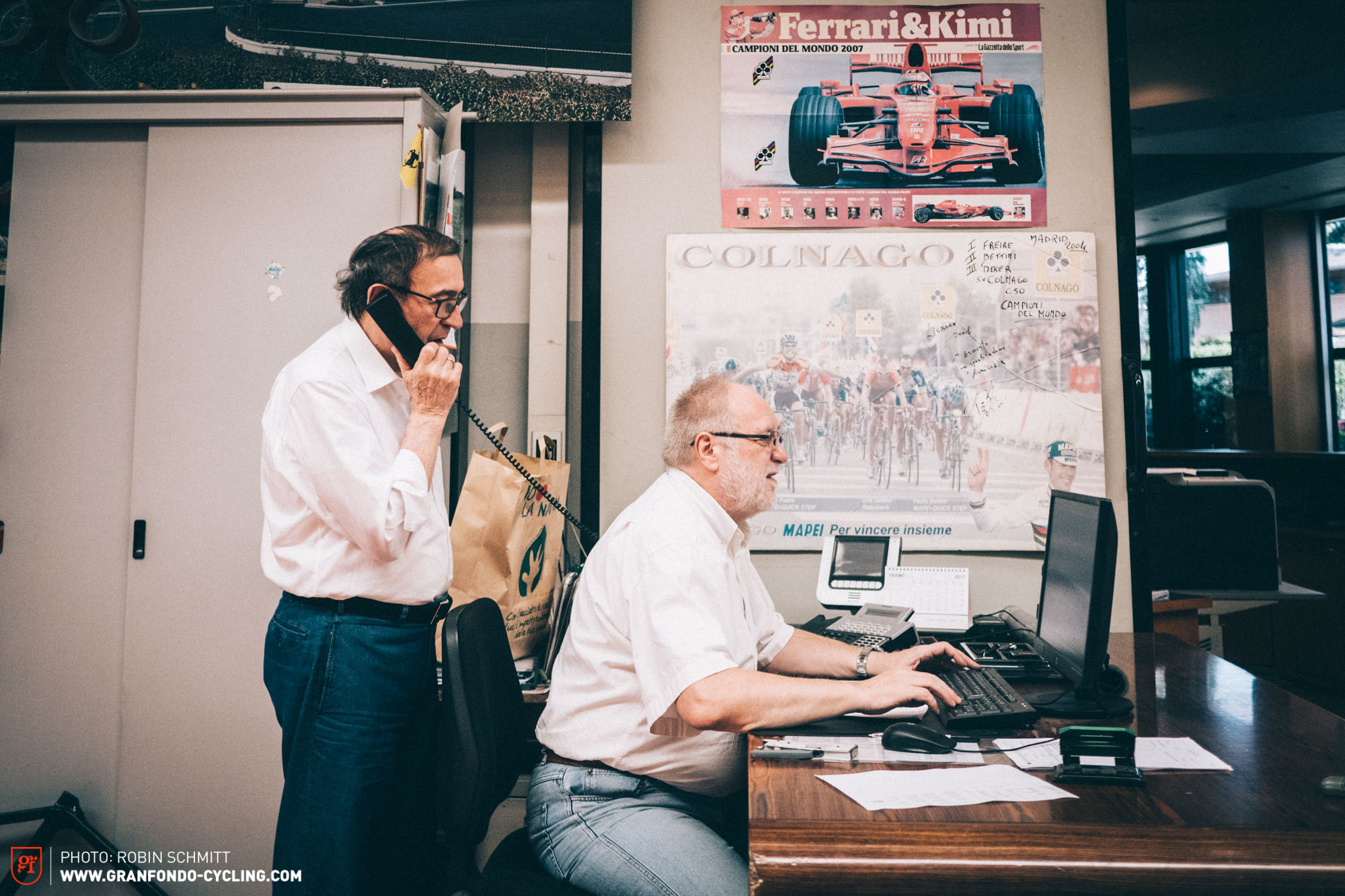

At our 41 Think Tank Brixen several suppliers echoed the same message. We have everything. We can provide brands with visibility on a daily, weekly, and monthly basis. We can share lead time variations, component shortages, colour changes, production bottlenecks, freight risks. But nobody asks. And even when someone finally does, the response is rarely consistent. Account managers hesitate, escalate internally, promise to check with management or IT, but eventually the process dies somewhere in the chain. Sometimes the data arrives once, sometimes not at all, and often only after manual work that nobody sustains regularly. The result is predictable. Whatever information comes through arrives late, sporadically or in formats that make it almost impossible to act on it. Beneath all of this sits the same issue: a lack of trust.

The myth is not that data is missing. The myth is that brands know what to do with it.

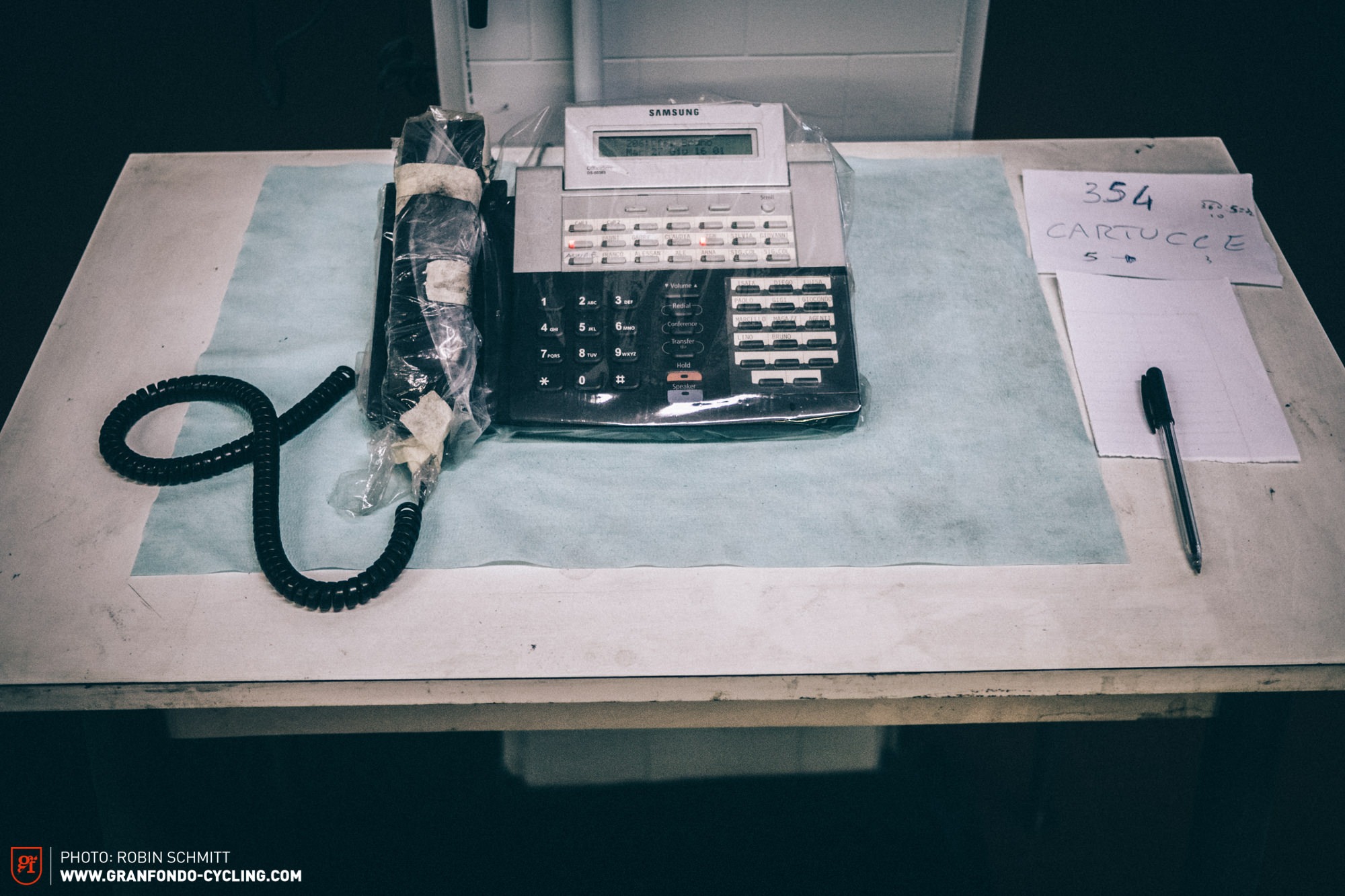

2. A culture that still behaves like a fax-era organisation

Digitalisation is not primarily a technological challenge. It’s a cultural one. The bike industry is still built on habits and communication patterns that belong to a different age. The only thing that has changed in the last twenty years is that email killed the fax. Everything else remained almost untouched.

Some examples that recur across companies of every size:

Forecasts exchanged as static spreadsheets

Production updates sent in irregular email bursts

Dealers placing orders blind, with no visibility of stock or inbound shipments

Brands adjusting their own forecasts based on “gut feeling”

Suppliers producing without real demand signals

Critical updates getting lost in internal threads and message chains

Systems running as isolated islands with no integration

Decision making based on outdated snapshots rather than real time information

This isn’t digitalisation – it’s just administrative life-support.

When a market becomes volatile, unpredictable and globally interconnected, such a structure collapses. Which is exactly what we have experienced, are still experiencing – and will experience again.

The industry keeps repeating the same cycle every few years. Overconfidence. Overproduction. Overstock. Panic. Discounts. No stock. Panic again. Back to overconfidence. The loop never ends because the underlying systems never evolve.

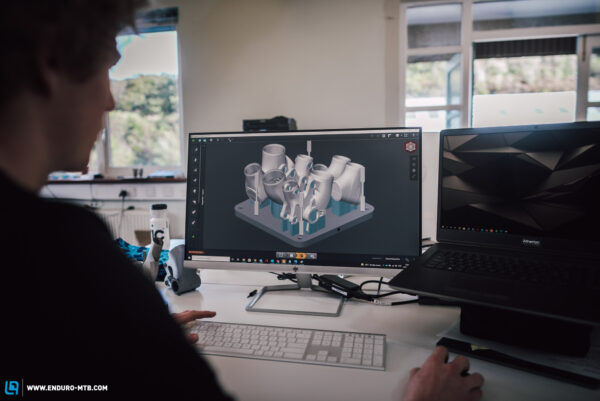

3. The industry that builds high tech bikes but still runs low tech operations

There is an uncomfortable paradox at the heart of this industry.

We build carbon frames with sub millimetre tolerances.

We machine cassettes with aerospace-grade precision.

We design motors that speak to ecosystems of sensors.

We integrate batteries, displays, firmware and diagnostics.

We create products that depend on digital layers to function.

And yet, many companies still manage their core operations with tools that would embarrass a mid-sized factory in almost every other industry.

Where automotive, consumer electronics, logistics and fashion already operate with shared data ecosystems, automated planning, real time visibility and predictive modelling, cycling still struggles to connect an OEM ERP with a brand ERP. We are not talking about AI, robotics or quantum computing. We are talking about the absolute basics of digital business.

This contradiction has consequences far beyond efficiency. It affects competitiveness, resilience and the ability to react to sudden shifts. The brands that treat digitalisation as optional are the same ones that end up reacting months late to demand shifts, losing cash, overbuilding inventory and suffocating their dealers.

Digitalisation is not a nice-to-have. It’s crucial to survive.

4. Why digitalisation is treated like science fiction in cycling

In most industries digitalisation is a solved problem. It’s mature, proven, accessible and well understood. But in cycling it still triggers resistance, confusion or even fear. Why?

There are several structural reasons:

Reason #1: Fragmented value chain

Cycling depends on a globally dispersed network of suppliers that operate with very different levels of maturity. Some are world class. Others are still struggling to develop a basic structure. Harmonising data across Asia, Europe and North America requires alignment that the industry has never had.

Reason #2: Lack of ownership

Nobody feels responsible for the integration. OEMs think brands should drive it. Brands think OEMs should provide it. Distributors feel they are the last to know. Dealers are expected to adapt. As long as digitalisation has no owner, nothing moves.

Reason #3: Legacy habits

Companies run on habits created in the nineties and reinforced during the “golden years” of easy growth. When business grows naturally, no one questions inefficiency. But when the market collapses, inefficiency becomes fatal.

Reason #4: Talent gap

The industry is full of passionate cyclists and strong product people. But digital transformation requires process engineers, data architects, system integrators and analysts. Positions that many brands still underestimate or fail to attract.

Reason #5: Cost aversion

Digitalisation is perceived as expensive, long and complicated. So companies procrastinate until the pain of staying the same becomes higher than the pain of changing. But by then the damage is done.

The result is an industry that keeps talking about digitalisation as if it were a faraway project. A future improvement. An innovation on a five year roadmap. Meanwhile competitors in other verticals solved these issues in 2008.

5. What we saw clearly in Brixen

Brixen revealed a truth that is almost too obvious. Every link of the value chain sees the same problem, but nobody has the mandate, structure or leverage to solve it.

Suppliers say they can provide daily data feeds.

OEMs say they can integrate but only if brands request it.

Brands say they want digitalisation but do not know where to start.

Distributors say they lack visibility from brands.

Dealers say they are flying blind.

A perfect example of hot-potato throwing across the entire value chain. The entire industry sees the same elephant. Everyone describes it. Most don’t “move” it.

This is why digitalisation conversations feel repetitive. Everyone already knows the diagnosis. Everyone knows the consequences. And everyone knows the next crisis will be worse if data remains isolated.

6. The cost of operating without horizontal data flow

Without shared intelligence the industry creates friction at every level.

Forecasts are inaccurate

Cash flow becomes unpredictable

Lead times oscillate violently

Warehouses fill and empty at the wrong moments

Dealers lose trust

Discounts become the default crisis management tool

Marketing becomes blind

Product planning becomes reactive

Sustainability becomes theatre

Customer experience becomes inconsistent

A product centric industry without data is like a high performance bike with square wheels. The engineering can be beautiful, but the ride will always be terrible.

7. The real leap: From isolated data to shared intelligence

Digitalisation is not about fancy software. And it’s not about dashboards that look like a spaceship cockpit either. It’s not about hiring a Chief Digital Officer and pretending the problem is solved.

The real leap comes from:

Connecting ERP systems across suppliers and brands

Building shared visibility of stock, demand and inbound

Creating real time planning instead of static snapshots

Allowing data to travel horizontally, not only vertically

Treating information as a shared asset, not a private bargaining chip

Removing friction, not piling on more reporting layers

Once information flows, everything changes. Planning increases accuracy. Production becomes stable. Dealers regain confidence. Cash flow becomes predictable. Crises become manageable.

Is this complex? Yes.

But is it impossible? Absolutely not.

Other industries have done it for decades.

8. Why the next five years will define who survives

Digitalisation is no longer a competitive advantage. It’s the entry ticket for those who want to be competitive in the short term. Brands that fail to adapt will very soon lose control of their value creation and eventually collapse into irrelevance or dependency.

Asian manufacturers are incredibly reliable and operationally disciplined. Workforce retention is high, processes run consistently, and scaling capacity is something they do with remarkable stability. But their digital systems often lag behind. Many factories still rely on manually maintained Excel files for core processes. Some ERP setups look and behave like legacy environments. Planning tools are fragmented or outdated, creating gaps rather than clarity.

So the West is not behind because Asia is hyper digitalised. The West is behind because both sides of the industry are still trapped in legacy structures that cannot support the volatility of the modern market.

This is why the 2025 to 2030 window matters so much. The brands and manufacturers that manage to build real shared data intelligence, regardless of geography, will dictate speed, efficiency and market rhythm. Those that do not will keep mistaking motion for progress until the market decides for them.

The real divide is not East versus West. It is digital maturity versus operational inertia.

9. The cultural shift the industry avoids but desperately needs

Digitalisation is not a spreadsheet upgrade. It’s a cultural shift. It forces transparency between partners who once hid information. It forces departments to collaborate instead of defending territories. It forces leaders to make decisions based on real flow, not habit.

And there is another layer the industry rarely admits. A significant part of the decision making class still treats IT as a black box. Many managers in their forties, fifties and sixties grew up professionally in an era where digital systems were peripheral, not central. For them digitalisation often feels risky, opaque or threatening. The fear is not that data will be wrong. The fear is that data will fall into the wrong hands. The result is resistance disguised as caution.

Once a company sees its own data clearly excuses disappear. Accountability appears. And the culture either grows or breaks. This is why many resist it. Digitalisation exposes the truth. And truth is uncomfortable for organisations built on habit, hierarchy and selective visibility.

10. Shared Intelligence and the Need for a Neutral Data Steward

During the ThinkTank in Brixen one idea kept resurfacing. The industry might require a neutral and independent entity responsible for managing the shared data infrastructure the sector has never been able to build on its own. A structure with no commercial agenda and no political alliances, acting as a system steward rather than a market player.

Such an entity wouldn’t replace the digitalisation efforts of individual companies. It would orchestrate them. It would provide the horizontal visibility that suppliers, OEMs, brands, distributors, and dealers all say they need – yet none can create on their own.. And it would lower the fear that has paralysed the industry for years. The fear of sharing data. The fear of losing advantage. The fear of revealing internal weaknesses.

If this structure had existed the last few years would have looked very different. The overstock crisis wouldn’t have disappeared, but it would have been recognised months earlier. Production signals would not have collapsed as violently. Suppliers would not have ramped up blindly. Dealers would not have ended up with warehouses full of products.

A neutral data steward wouldn’t have solved every problem.

But it would have prevented the industry from walking into the storm with its eyes closed.

The absence of shared data governance is not a technological gap. It’s the missing layer of organisational maturity that explains why every crisis feels both predictable and unavoidable.

11. The Shift We Need: From Local Fixes to a Global Data Ecosys

Digitalisation isn’t a vision of the future. It’s the price of entry for anyone who wants to stay competitive now. This industry has lost enough time – with excuses, with fear, with committees that confuse motion for progress.

We have described the symptoms. But taken together, they reveal something deeper than operational friction: an industry that lacks alignment, wastes resources, and makes decisions in the dark.

We burn money without even noticing it.

We operate from a position of weakness.

We lose clarity – and with it, sound judgement.

We react instead of leading.

And until the industry moves from isolated data to shared intelligence, nothing will fundamentally change. The technology is ready. The knowledge exists. What’s missing is the courage to treat digitalisation not as a future ambition, but as the foundation that should have been built years ago.

Without that shift, the next crisis will look like the last one. Only more expensive.

And with even less margin for error.

The irony is hard to ignore. We are in 2025, surrounded by technologies that redefine what is possible – AI that learns in seconds, systems that predict with astonishing accuracy, tools that build and optimise at a scale previously unknown to humanity. And yet our industry still moves in fragments, disconnected and slow, as if held together by the visible cables of a low-budget space movie. But this is not our fate. It’s our threshold. Everything we need already exists – the tools, the talent, the urgency. What is missing is the will. The decision to lead instead of waiting for someone else to fix it. The courage to stop patching old structures and start building new ones.

The real question is not whether we digitalise. It’s has the guts to face the transparency digitalisation inevitably brings – and who will lead the shift toward a truly global, connected ecosystem instead of creating the next generation of fragmented, country-scale solutions.

12. Lead the Shift: Bring Your Solutions to the Table

If you are a startup or company working on solutions to the industry’s digitalisation challenge – we want to hear from you: What are your ideas? Where do you hit the limits? And what support do you need to turn potential into real momentum?

At 41 Publishing, we are committed to accelerating and supporting this transformation. We are building platforms – from our Think Tanks to the Cycling Innovation Accelerator (C.I.A.) to the Top100 Leadership Summit – where your expertise can play a decisive role.

If you are ready to contribute, shape, or accelerate meaningful initiatives, reach out to us and let’s get this ball rolling together: robin@41publishing.com

The future of cycling will be built by those who dare to build it now.

Overview – The Brixen Bike Papers

This article is part of the Brixen Bike Papers – a 41 Publishing initiative from our 2025 Think Tank in Brixen with the goal of building a better bike world. A series of industry analysis and essays diving deep into the uncomfortable truths, hidden opportunities, and real changes our industry needs. Click here for the overview of all released stories.

Did you enjoy this article? If so, we would be stoked if you decide to support us with a monthly contribution. By becoming a supporter of GRAN FONDO, you will help secure a sustainable future for high-quality cycling journalism. Click here to learn more.

Words: Juansi Vivo, Robin Schmitt Photos: diverse