December 9, 2025 — 6:30pm

Save

You have reached your maximum number of saved items.

Remove items from your saved list to add more.

Save this article for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them anytime.

Got it

How Olafur Eliasson’s work looks to you depends on where you are standing. Move a little to the left and all you will see is a plain, clear diamond hanging in the air. Take a couple of steps and look through what at first looks like a sheet of plastic, however, and suddenly the diamond is a world of colours.

Perspective, putting yourself in the shoes of others, and challenging your own worldview are threads that run through the acclaimed artist’s new exhibition, Presence, in which the audience are just as important as the works they are looking at.

Artist Olafur Eliasson.DPA

Artist Olafur Eliasson.DPA

The first thing you see is a sea of white Lego, laid out on a long table with benches positioned on either side. This is The Cubic Structural Evolution Project (2004) and it invites visitors to sit down and begin the exhibition by being part of it. All the ideas Eliasson has threaded through Presence – at Brisbane’s Queensland Art Gallery/Gallery of Modern Art – are distilled into this deceptively simple installation; fragility, community, the power of the individual, of choice.

In between the loose blocks is the shape of a chaotic city, built by many hands. Some visitors have built replicas of existing structures – Stonehenge, a Roman aqueduct – others have created fantastical structures that could not exist in the real world. Then there are the things that aren’t buildings. Faces, monstrous figures, complex shapes. As a visitor, you can pick your poison: add to what’s already there, look but keep walking, or destroy someone else’s work. Just past the table, by the window of the gallery, is a blinking light with a twinkle of colour. Your lost lighthouse (2020) looks gentle and delicate, but underneath it is sending out one continuous message though Morse code: SOS.

Presence is a complex dance between beauty and dread, discomfort and inclusion, horror and hope – for all the bright colours threaded through the rooms, this is a show that is firmly planted in shades of grey. It’s in this space that Eliasson hopes to make genuine and meaningful progress in the climate crisis. Connectivity, he underscores, is the key. And a willingness to be uncomfortable.

“Connectivity is a sense of inclusion, and for that, we need to open our eyes [so] we can be inclusive with people we don’t agree with,” he says. “Climate justice is to bring the people working in the coal mines to the table and make sure they get another job … We need to give them something else to do. Otherwise, this is going to be unfair. It’s not the miners’ fault that there is climate crisis.”

Your negotiable vulnerability seen from two perspectives. Studio Olafur Eliasson

Your negotiable vulnerability seen from two perspectives. Studio Olafur Eliasson

He’s created a delicate balance in this exhibition. The fact that there is a climate crisis is unambiguously spelled out in his work, The glacier melt series 1999/2019, a series of paired photographs of different glaciers taken 20 years apart. It’s a confronting series; in most, the glaciers have dramatically receded. “I say I’m positive, but I’m f—ing desperate. I’m so anxious about where this is going,” he says.

Most of the other works, however, are geared more towards the solution, not the problem. Presence is the result of a close collaboration between the gallery and Eliasson, with curator Geraldine Kirrihi Barlow undertaking a residency with the artist at his Berlin-based studio.

Presence sees the return of Riverbed (2014), which was last displayed at QAGOMA in 2019 as part of the group exhibition Water. Here, Eliasson brings the outside indoors in an uncanny juxtaposition of nature against white walls and artificial light.

Like The Cubic Structural Evolution Project, how you engage with the work is up to you. An incline is covered with pebbles of all shapes and sizes, and a running stream of water snakes its way down the entire room. You can stand at the base and look up at it, or you can hike your way up.

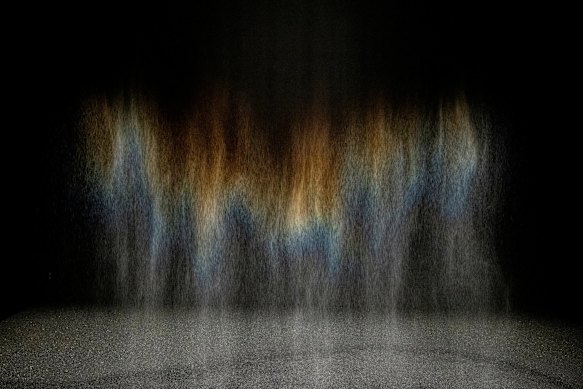

In Beauty (1993), Eliasson advises the audience to stand near enough to let the water gently dust your skin.Kazuo Fukunaga

In Beauty (1993), Eliasson advises the audience to stand near enough to let the water gently dust your skin.Kazuo Fukunaga

As I’m making my ungainly way across the rocks, one woman walks straight into the water, letting it run across her feet. Maybe for some visitors it’s peaceful, beautiful. For me, there is an edge of horror – if we don’t get moving on a solution, maybe this will be one of the few ways future generations can experience nature – artificially. Eliasson explains that part of the idea is that it challenges the experience of being in a museum – it forces you to be present, makes things a bit more difficult, means you can’t be passive.

The oldest work in the show is also one of its highlights. Set apart in its own darkened room, in Beauty (1993) light plays across a mist of water. Initially we all stand well away, until Eliasson insists we move up close. It’s beautiful watching from afar, as the colours dance over the droplets, but when you take Eliasson’s advice and stand close enough that the water gently dusts your skin, suddenly the entire world becomes this one work and for a few moments everything else falls away.

In one of the final rooms, the work that gave this exhibition its name looms over the space, with what looks like a glowing giant yellow orb taking up residence in the corner. The work is a nod to one of Eliasson’s best-known installations, The Weather Project (2003), at the Tate Modern in London.

Surrounded by mirrors, what is actually a quarter wedge is made whole, and the light that comes off it is what an optimist might call a warm yellow with everything else in shades of grey, or what a pessimist could call an apocalyptic desertscape where the heat of the sun feels far too close. Whether by design or necessity, it feels like Presence has ratcheted up the tension since The Weather Project, bringing the orb lower and closer.

Olafur Eliasson’s Presence is one of three new works created for the exhibition. Chloë Callistemon, QAGOMA

Olafur Eliasson’s Presence is one of three new works created for the exhibition. Chloë Callistemon, QAGOMA

Presence is one of three new works created for the exhibition. The other two are Your negotiable vulnerability seen from two perspectives (2025) and Your truths (2025). In the latter, a series of large lenses are set up in front of a clear plastic curtain being buffeted by a series of fans. As you walk along, your view changes depending on what lens you are looking through. Suddenly, there are colours in what was previously transparent; white becomes black. It’s beautiful, yes, but it’s more than a gimmick or a fleeting novelty. We all see things differently – but staying firm to the notion that your truth is the only truth helps no one.

“Art, for me, is not outside the world. It’s not like you step out of the world, into a museum, out of the world, into a theatre, out of the world, into reading a book,” he says. “If anything, one could say reading a book is looking at the world through a microscope.” Culture and art, Eliasson reflects, “is a language that pretty much everyone speaks some version of”.

“Profitability is still the biggest driver of the environmental crisis. So we need to make it profitable to not damage the planet,” says Eliasson. Individuals can make a difference, he underscores: “The micro has the power.”

Olafur Eliasson: Presence is at the Gallery of Modern Art (QAGOMA), Brisbane, from December 6 to July 12.

The author travelled to Brisbane as a guest of QAGOMA.

The Booklist is a weekly newsletter for book lovers from Jason Steger. Get it delivered every Friday.

Save

You have reached your maximum number of saved items.

Remove items from your saved list to add more.

Most Viewed in CultureFrom our partners