Expected IC signal

The incident VUV flux is attenuated, so that it follows φ0e−αz, in which α is the VUV attenuation coefficient. The number of excited 229Th nuclei in a target of length L should go as57

$${N}_{{\rm{e}}}\approx \frac{4}{6}\frac{{\lambda }^{2}}{2{\rm{\pi }}}\frac{{n}_{{\rm{Th}}}}{{\varGamma }_{{\rm{L}}}}\frac{T|\widetilde{n}{|}^{2}}{{\rm{Re}}[\widetilde{n}]}\frac{{\varphi }_{0}(1-{{\rm{e}}}^{-\alpha L})}{\alpha }\times \frac{1}{1+4{\left(\frac{\delta }{{\varGamma }_{{\rm{L}}}}\right)}^{2}}\times \left(\frac{{t}_{{\rm{e}}}}{{\tau }_{{\rm{rad}}}}\right),$$

(2)

in which λ is the vacuum transition wavelength, nTh is the density of 229Th in the 229ThO2 target, Γrad = 1/τrad is the vacuum radiative decay rate, ΓL is the VUV laser bandwidth, ΓIC = 1/τIC is the IC decay rate, δ is the laser detuning, φ0 is the incident laser photon flux, L is the target thickness, T is the transmission of the VUV laser into the target and \(\widetilde{n}=n-{\rm{i}}\kappa \) is the complex index of refraction with κ = λα/4π. The target was produced using a 0.75:0.25 229Th:232Th isotope mix from Oak Ridge National Laboratory, leading to an effective 229Th density of nTh = 0.75 × 2.28 × 1022 cm−3 (ref. 47).

From the number of excited 229Th nuclei, the number of detected IC electrons is given by

$${N}_{\det }={\eta }_{{\rm{e}}}{\eta }_{{\rm{c}}}{N}_{{\rm{e}}}\times {{\rm{e}}}^{-{t}_{{\rm{i}}}/{\tau }_{{\rm{IC}}}}$$

(3)

in which ηe is the extraction efficiency from the 229ThO2 target, ηc is the collection efficiency and ti is the start of the acquisition time window. The extraction efficiency represents the probability that an IC electron is able to leave the 229ThO2 target and combines many physical processes, such as whether the electron is promoted high enough into the conduction band to overcome the ionization energy barrier (either by being in a state above the ionization energy or tunnelling), whether the electron inelastically scatters, whether surface conditions are favourable and so on. Owing to all of these confounding factors, theoretical calculation of ηe is difficult and it must be estimated from experiments. To do this, we make the assumption that the probability for a photoelectron promoted by a VUV photon to leave the target is the same as an IC electron promoted by an excited 229Th nucleus. By making this assumption, we are able to use the efficiency with which photoelectrons are generated by our VUV laser system to obtain an estimate of Tηe. The collection efficiency ηc is simply the efficiency with which electrons that leave the target are detected on the MCP given the voltage biasing and magnetic field configuration used in the experiment. This can be readily determined by measuring the ratio of the number of photoelectrons collected on the MCP front plate relative to the number of photoelectrons leaving the target.

Using the values listed in Extended Data Table 1, the expected on-resonance IC signal was estimated to be \({N}_{{\rm{\det }}}/(\hbar {\omega }_{0}{\varphi }_{0}{t}_{{\rm{e}}})\,=\) \(0.1{5}_{-0.09}^{+0.25}\,{{\rm{e}}}^{-}\,{{\rm{\mu }}{\rm{J}}}^{-1}\) per shot.

Quenching of ASE in Xe four-wave mixing

The four-wave mixing process can produce a beam of ASE along the beam axis, complicating detection. The origin of the ASE is resonant excitation by the 249.6-nm laser of the \(5{{\rm{p}}}^{6}\,\genfrac{}{}{0ex}{}{1}{}{S}_{0}\to 5{{\rm{p}}}^{5}\,\left(\,\genfrac{}{}{0ex}{}{2}{}{P}_{3/2}^{^\circ }\right)\,6{{\rm{p}}}^{2}\,{[1/2]}_{0}\) transition. Any Xe population not participating in the four-wave mixing process will be left in the excited two-photon state. This \(5{{\rm{p}}}^{5}\,\left(\,\genfrac{}{}{0ex}{}{2}{}{P}_{3/2}^{^\circ }\right)\,6{{\rm{p}}}^{2}\,{[1/2]}_{0}\) (abbreviated as 6p2 [1/2]0) state will then decay to the \(5{{\rm{p}}}^{5}\,\left(\,\genfrac{}{}{0ex}{}{2}{}{P}_{3/2}^{^\circ }\right)\,6{{\rm{s}}}^{2}\,{[3/2]}_{1}^{^\circ }\) (abbreviated as \(6{{\rm{s}}}^{2}\,{[3/2]}_{1}^{^\circ }\)) state by 828-nm emission in about 30 ns and the \(6{{\rm{s}}}^{2}\,{[3/2]}_{1}^{^\circ }\) state will decay to the 1S0 ground state by emission of a 147-nm photon in about 3.7 ns. If the Xe pressure is in the several hundred Pa range, as it is for efficient four-wave mixing, there are enough nearby Xe atoms that they may reabsorb these 828-nm and 147-nm photons. Effectively, this leads to radiation trapping, which extends the effective fluorescence lifetime of the Xe spontaneous emission58. At the same time, the 828-nm/147-nm spontaneous emission will experience gain as it stimulates Xe in the excited 6p2 [1/2]0 and \(6{{\rm{s}}}^{2}\,{[3/2]}_{1}^{^\circ }\) to emit, yielding ASE. This gain will be highly directional, as the excited Xe will essentially lie in a column defined by the propagation of the 249.6-nm pulse of the pump laser. This interplay between radiation trapping and ASE will then yield bidirectional emission from the Xe cell along the pumping axis, which will have a timescale much longer than the spontaneous emission lifetime of the excited states59.

To mitigate this effect, we introduce N2 gas in the Xe, which quenches the excited state Xe population through collision.

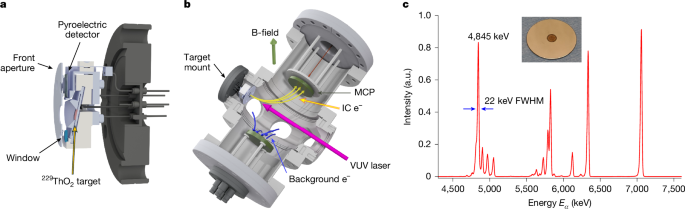

Simulation of electron trajectories

SIMION60 simulations were carried out to determine a combination of voltage biasing and static magnetic field that would guide IC electrons to our detector while diverting background photoelectrons to a secondary electrode. The voltage biasing chosen during the IC observation period was to have the target at −405 V, the front aperture of the target mount at +135 V, the front of the detection MCP at +140 V and the secondary electrode at +2,500 V. The magnetic field was set to about 3–5 G. As can be seen in Extended Data Fig. 1a, under the voltage biasing described, there is a ‘saddle’ in the potential through which the IC electrons that have been accelerated by our target mount system can be made to travel through by the magnetic field. Meanwhile, as can be seen in Extended Data Fig. 1b, electrons that are generated randomly throughout the chamber with about 8 eV of kinetic energy either crash into the chamber wall or fall into the sacrificial electrode.

Preparation of the target

The target used in this study was prepared in an electrodeposition buffer solution of NaOH and sulfuric acid. 229Th material was deposited onto the stainless steel disc until target activity was reached, at which a quench was performed with ammonium hydroxide. The disc was then heated overnight at 200–300 °C in ambient atmosphere.

Although the electrodeposited target is probably a mixture of Th hydroxides, oxides and metal impurities, the use of low-impurity (>99.99% grade) chemicals during electrodeposition and heat treatment in air lead us to assume that it is predominantly Th in an oxidized state. As the most stable oxide form, we assume that the target is predominately 229ThO2.

IC rate derivation

We consider the IC processes in an insulator, when the bandgap Δ is smaller than the nuclear isomer energy ωnuc. In the IC process, the nuclear excitation is transferred to the electrons, spawning a particle–hole pair, with a valence band electron promoted into the conduction band, leaving behind a hole in the valence band; see Fig. 3a.

The 229Th nuclear subsystem is modelled as two distinct energy levels: the ground state |g⟩ with nuclear spin Ig = 5/2 and the excited (isomeric) state |e⟩ with Ie = 3/2, separated by the energy gap ωnuc.

The IC process is mediated by the HFI. In a crystal, containing \({\mathcal{N}}\) 229Th nuclei with one 229Th per unit cell, HFI reads

$$W({\bf{r}})=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{\nu =1}^{{\mathcal{N}}}{\mathcal{M}}({{\bf{R}}}_{\nu })\cdot {\mathcal{T}}\,({\bf{r}}-{{\bf{R}}}_{\nu }),$$

(4)

in which we sum over unit cells, \({\mathcal{M}}({{\bf{R}}}_{\nu })\) is a 229Th nuclear magnetic moment operator and the 229Th-centred \({\mathcal{T}}\) is a rank-1 tensor acting on the electronic degrees of freedom. The nuclear electric-quadrupolar and higher-rank HFI interactions can be added in a similar fashion. For 229ThO2, owing to the cubic symmetry, the electric-quadrupole contribution vanishes.

To compute the IC rate, we use Fermi’s golden rule. The initial state of the electron subsystem is a fully occupied valence band \(| \mathop{0}\limits^{ \sim }\rangle \) and the final state is the particle–hole excitation \({a}_{c{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}}^{\dagger }{a}_{v{\bf{q}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}|\widetilde{0}\rangle \) with energy εck − εvq, in which εck and εvq are the band functions of the conduction (c) and the valence (v) bands. Then, the final state quantum numbers are spanned by crystal momenta k, q and two electron spin projections. We also sum over the nuclear ground state magnetic quantum numbers Mg and average over the nuclear isomer state magnetic quantum numbers Me,

$$\begin{array}{c}{\varGamma }_{{\rm{IC}}}^{({\mathcal{N}}\,)}=\frac{2{\rm{\pi }}}{\hbar }\frac{1}{2{I}_{{\rm{e}}}+1}\sum _{{M}_{{\rm{g}}}{M}_{{\rm{e}}}}\sum _{{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}{\int }_{{\rm{BZ}}}{d}^{3}k{\int }_{{\rm{BZ}}}{d}^{3}q|\langle c{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}|{W}^{{\rm{ge}}}|v{\bf{q}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}\rangle {|}^{2}\\ \,\delta ({\varepsilon }_{c{\bf{k}}}-{\varepsilon }_{v{\bf{q}}}-{\omega }_{{\rm{nuc}}}).\end{array}$$

(5)

The integrations are carried over the Brillouin zone (BZ). We use the conventions from ref. 41 in our derivation.

The HFI (equation (4)) is cell-periodic and its matrix element ⟨ckσc|Wge∣vqσv⟩ between Bloch functions can be reduced from an integration over the entire crystal to an integration over a single unit cell. The result reads

$$\langle c{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}|{W}^{{\rm{ge}}}|v{\bf{q}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}\rangle =\delta ({\bf{k}}-{\bf{q}}){W}_{c{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}v{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}^{{\rm{ge}}}({\bf{k}})$$

(6)

with

$${W}_{c{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}v{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}^{{\rm{ge}}}({\bf{k}})\equiv \frac{{(2{\rm{\pi }})}^{3}}{\varOmega }\langle g|{\mathcal{M}}|e\rangle \cdot {\int }_{\varOmega }{d}^{3}r{u}_{c{\bf{k}}}^{* }({\bf{r}}){\chi }_{{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}}^{\dagger }{\mathcal{T}}({\bf{r}}){\chi }_{{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}{u}_{v{\bf{k}}}({\bf{r}}).$$

(7)

Here Ω is the unit cell volume, u…(r) are cell-periodic envelopes of Bloch functions41 and χ are the conventional electron spinors. Note that the cell-periodicity imposes conservation of crystal momentum, k = q.

Now, with this matrix element, we evaluate the IC rate.

$$\begin{array}{c}{\varGamma }_{{\rm{IC}}}^{({\mathcal{N}}\,)}=\frac{2{\rm{\pi }}}{\hbar }\frac{1}{2{I}_{{\rm{e}}}+1}\sum _{{M}_{{\rm{g}}}{M}_{{\rm{e}}}}\sum _{{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}\int {d}^{3}k\int {d}^{3}q|{W}_{c{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}v{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}^{{\rm{ge}}}({\bf{k}}){|}^{2}\\ \,\delta ({\bf{k}}-{\bf{q}})\delta ({\bf{k}}-{\bf{q}})\delta ({\varepsilon }_{c{\bf{k}}}-{\varepsilon }_{v{\bf{q}}}-{\omega }_{{\rm{nuc}}}).\end{array}$$

(8)

There is a product of two identical delta functions. q is replaced by k while integrating over q, but we encounter \(\delta ({\bf{0}})={\mathrm{lim}}_{\Delta {\bf{q}}\to 0}\delta (\Delta {\bf{q}})\). Using the following identity for each component of Δq:

$$\mathop{\mathrm{lim}}\limits_{\Delta {q}_{x}\to 0}\delta (\Delta {q}_{x})=\mathop{\mathrm{lim}}\limits_{{L}_{x}\to \infty }\mathop{\cos }\limits_{\Delta {q}_{x}\to 0}\frac{1}{2{\rm{\pi }}}{\int }_{-{L}_{x}/2}^{{L}_{x}/2}{{\rm{e}}}^{{\rm{i}}\Delta {q}_{x}x}{\rm{d}}x=\frac{{L}_{x}}{2{\rm{\pi }}},$$

in which Lx is the crystal size in the x-direction, we can show that

$$\mathop{\mathrm{lim}}\limits_{\Delta {\bf{q}}\to 0}\delta (\Delta {\bf{q}})=\frac{{V}_{{\rm{xtal}}}}{{(2{\rm{\pi }})}^{3}},$$

in which the crystal volume Vxtal = LxLyLz. This is similar to the formal time-domain limit in deriving Fermi’s golden rule; see, for example, p. 72 of ref. 61.

Thereby, the IC rate per crystal volume

$$\begin{array}{c}{\varGamma }_{{\rm{IC}}}^{({\mathcal{N}}\,)}/{V}_{{\rm{xtal}}}=\frac{2{\rm{\pi }}}{\hbar }\frac{1}{{(2{\rm{\pi }})}^{3}}\frac{1}{2{I}_{{\rm{e}}}+1}\sum _{{M}_{{\rm{g}}}{M}_{{\rm{e}}}}\sum _{{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}{\int }_{{\rm{BZ}}}{d}^{3}k|{W}_{c{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}v{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}^{{\rm{ge}}}({\bf{k}}){|}^{2}\\ \,\delta ({\varepsilon }_{c{\bf{k}}}-{\varepsilon }_{v{\bf{k}}}-\hbar {\omega }_{{\rm{nuc}}})\end{array}$$

(9)

The assumption made during the derivation was that all \({\mathcal{N}}\) 229Th nuclei were initially in the excited (isomer) state. Consider an ensemble of quantum emitters, with N(t) being the number of emitters in the excited state at time t, with a single emitter decay rate γ and

$$\begin{array}{l}{\rm{d}}N/{\rm{d}}t\,=\,-\gamma N(t)\Rightarrow N(t)=N(0)\exp -\gamma t\\ \,\,\,\Rightarrow \,{\rm{ensemble}}\,{\rm{decay}}\,{\rm{rate}}\,\varGamma \\ \,\,\,=\,-{\rm{d}}N/{\rm{d}}t\\ \,\,\,=\,\gamma N(0)\exp -\gamma t.\end{array}$$

(10)

We see that the ensemble decay rate Γ at t = 0 is γN(0). The experimentally relevant excited state population, however, decays as exp−γt. On the basis of this discussion, we define the experimentally measured IC decay rate

$${\varGamma }_{{\rm{IC}}}={\varGamma }_{{\rm{IC}}}^{({\mathcal{N}}\,)}/{\mathcal{N}}=\varOmega {\varGamma }_{{\rm{IC}}}^{({\mathcal{N}}\,)}/{V}_{{\rm{xtal}}}.$$

(11)

Following the derivation of interband electromagnetic absorption rates41, we define a surface SE of constant energy in k-space through an implicit relation εck − εvk = ħωnuc. If the matrix element remains reasonably constant on SE, the rate simplifies to

$${\varGamma }_{{\rm{IC}}}=\frac{1}{{\tau }_{{\rm{IC}}}}=\frac{2{\rm{\pi }}}{\hbar }\frac{1}{2{I}_{{\rm{e}}}+1}\sum _{{M}_{{\rm{g}}}{M}_{{\rm{e}}}}\sum _{{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}\overline{|{W}_{c{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}v{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}^{{\rm{ge}}}({\bf{k}}){|}^{2}}{G}_{{\rm{cv}}}(\hbar {\omega }_{{\rm{nuc}}}).$$

(12)

with the JDOS

$${G}_{{\rm{cv}}}(E)=\frac{\varOmega }{{(2{\rm{\pi }})}^{3}}{\int }_{{\rm{BZ}}}{d}^{3}k\delta ({\varepsilon }_{c{\bf{k}}}-{\varepsilon }_{v{\bf{k}}}-E)=\frac{\varOmega }{{(2{\rm{\pi }})}^{3}}\int \frac{d{S}_{{\rm{E}}}}{|{\nabla }_{{\bf{k}}}{({\varepsilon }_{c{\bf{k}}}-{\varepsilon }_{v{\bf{k}}})}_{E}|}.$$

(13)

With this simplification, \(\overline{|{W}_{c{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}v{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}^{{\rm{ge}}}({\bf{k}}){|}^{2}}\) has the meaning of \(|{W}_{c{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}v{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}^{{\rm{ge}}}({\bf{k}}){|}^{2}\) averaged over the surface of constant energy SE.

This concludes the derivation of the IC rate (equation (1)).

Also worthy of mention, note that the electromagnetic absorption coefficient at laser frequency ωnuc is proportional to the same JDOS Gcv(ħωnuc). This can be used to back out the JDOS value from the laser absorption measurements at a frequency slightly detuned away from ωnuc.

To proceed with the computation of the hyperfine matrix element, we expand the functions u⁎ck(r) in terms of the Th atomic states. Owing to the short-range nature of the HFI, relativistic effects play an important role. As a result, we use relativistic Dirac spinors for the Th atomic states. However, equation (7) is given in terms of nonrelativistic (or scalar relativistic62) two-component spinors. Here, for simplicity, we replace equation (7) with

$${W}_{c{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}v{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}^{{\rm{ge}}}({\bf{k}})\equiv \frac{{(2{\rm{\pi }})}^{3}}{\varOmega }\langle \,g|{\mathcal{M}}|e\rangle \cdot {\int }_{\varOmega }{d}^{3}r{u}_{c{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}}^{\dagger }({\bf{r}}){\mathcal{T}}\,({\bf{r}}){u}_{v{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}({\bf{r}}),$$

(14)

in which \({u}_{n{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{n}}}}({\bf{r}})\) is now a four-component Dirac spinor with momentum k and spin projection σn.

The crystal function \({u}_{c{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}}({\bf{r}})\) (and similarly \({u}_{v{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}({\bf{r}})\)) may be expanded in terms of the Th atomic states of definite principle and angular momentum quantum numbers φnjlm(r)

$${u}_{c{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{n}}}}({\bf{r}})=\sqrt{\frac{\varOmega }{{(2{\rm{\pi }})}^{3}}}\sum _{njlm}{a}_{njlm}(c{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{n}}}){\varphi }_{njlm}({\bf{r}})+\ldots ,$$

(15)

in which the ellipsis denotes contributions from O atomic states, which, owing to their small overlap with the Th nucleus, do not affect the HFI matrix element. Using the expansion (14), we may write

$${W}_{c{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}v{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}^{{\rm{ge}}}({\bf{k}})=\sum _{njlm}\sum _{{n}^{{\prime} }{j}^{{\prime} }{l}^{{\prime} }{m}^{{\prime} }}{a}_{njlm}^{* }(c{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}){a}_{{n}^{{\prime} }{j}^{{\prime} }{l}^{{\prime} }{m}^{{\prime} }}(v{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}){\widetilde{W}}_{njlmn{j}^{{\prime} }{l}^{{\prime} }{m}^{{\prime} }}^{{\rm{ge}}},$$

(16)

in which \({\widetilde{W}}_{njlmn{j}^{{\prime} }{l}^{{\prime} }{m}^{{\prime} }}^{{\rm{ge}}}=\langle g|{\mathcal{M}}|e\rangle \cdot {\int }_{\varOmega }{d}^{3}r{\varphi }_{njlm}^{\dagger }({\bf{r}}){\mathcal{T}}({\bf{r}}){\varphi }_{{n}^{{\prime} }{j}^{{\prime} }{l}^{{\prime} }{m}^{{\prime} }}({\bf{r}})\).

Given the crystal functions and the atomic wavefunctions, the expansion coefficients anjlm(kσn) may be computed and the total HFI matrix element obtained. Here we make a simplifying assumption that only a few terms contribute substantially to the sum in equation (15). Furthermore, we shall neglect the contribution from cross terms in \({|{W}_{c{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}v{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}^{{\rm{ge}}}({\bf{k}})|}^{2}\). With these simplifications, the IC rate may be written as

$$\begin{array}{l}{\varGamma }_{{\rm{IC}}}\,\approx \,\frac{{\rm{\pi }}}{\hbar }\frac{1}{2{I}_{{\rm{e}}}+1}\sum _{{M}_{{\rm{g}}}{M}_{{\rm{e}}}}\sum _{njlm}\sum _{{n}^{{\prime} }{j}^{{\prime} }{l}^{{\prime} }{m}^{{\prime} }}{|{\widetilde{W}}_{njlm{n}^{{\prime} }{j}^{{\prime} }{l}^{{\prime} }{m}^{{\prime} }}^{{\rm{ge}}}|}^{2}\\ \,\,\times \,\sum _{{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}\frac{2\varOmega }{{(2{\rm{\pi }})}^{3}}{\int }_{{\rm{BZ}}}{d}^{3}k{|{a}_{njlm}(c{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}})|}^{2}{|{a}_{{n}^{{\prime} }{j}^{{\prime} }{l}^{{\prime} }{m}^{{\prime} }}(v{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}})|}^{2}\\ \,\delta ({\varepsilon }_{c{\bf{k}}}-{\varepsilon }_{v{\bf{k}}}-\hbar {\omega }_{{\rm{nuc}}}).\end{array}$$

(17)

Let us now consider the matrix element \({W}_{c{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}v{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}^{{\rm{ge}}}({\bf{k}})\) in more detail. Using the Wigner–Eckart theorem, we may write

$$\begin{array}{l}{\widetilde{W}}_{njlmn{j}^{{\prime} }{l}^{{\prime} }{m}^{{\prime} }}^{{\rm{ge}}}=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{\nu =-1}^{1}{(-1)}^{\nu +{I}_{{\rm{g}}}-{M}_{{\rm{g}}}+j-m}\left(\begin{array}{ccc}{I}_{{\rm{g}}} & 1 & {I}_{{\rm{e}}}\\ -{M}_{{\rm{g}}} & \nu & {M}_{{\rm{e}}}\end{array}\right)\\ \,\,\,\,\left(\begin{array}{ccc}j & 1 & {j}^{{\prime} }\\ -m & -\nu & {m}^{{\prime} }\end{array}\right)\langle g||{\mathcal{M}}||e\rangle \langle njl||{\mathcal{T}}||{n}^{{\prime} }{j}^{{\prime} }{l}^{{\prime} }\rangle .\end{array}$$

(18)

Here \(\langle g||{\mathcal{M}}||e\rangle \approx 0.84{\mu }_{{\rm{N}}}\) (μN is the nuclear magneton) is the reduced matrix element of the nuclear magnetic moment operator (see, for example, ref. 12) and \(\langle njl||{\mathcal{T}}||{n}^{{\prime} }{j}^{{\prime} }{l}^{{\prime} }\rangle \) is the reduced matrix element of the rank-1 electronic HFI tensor. Th off-diagonal HFI matrix elements are at least two orders of magnitude smaller than the diagonal ones, so the most important contributions to the IC rate come from terms with (njl) = (n′j′l′). The reduced matrix element \(\langle njl||{\mathcal{T}}||njl\rangle \) may be related to the ground state HFI constant Anjl through63

$${A}_{njl}=\frac{{\mu }_{{\rm{g}}}}{{I}_{{\rm{g}}}\,j}\frac{(2j)!}{\sqrt{(2j-1)!(2j+2)!}}\langle njl||{\mathcal{T}}||njl\rangle ,$$

(19)

in which μg = 0.360(7)μN is the magnetic moment of the ground nuclear state64. With this, the summations over Mg and Me in equation (16) may be carried out, giving

$$\sum _{{M}_{{\rm{g}}}{M}_{{\rm{e}}}}{|{\widetilde{W}}_{njlmnjl{m}^{{\prime} }}^{{\rm{ge}}}|}^{2}=\frac{1}{3}\left[\mathop{\sum }\limits_{\nu =-1}^{1}{\left(\begin{array}{ccc}j & 1 & j\\ -m & \nu & {m}^{{\prime} }\end{array}\right)}^{2}\right]{\langle g||{\mathcal{M}}||e\rangle }^{2}{\langle njl||{\mathcal{T}}||njl\rangle }^{2}.$$

(20)

To proceed, we make a further assumption that the quantity in the second line of equation (16) does not depend strongly on the magnetic quantum numbers m and m′, that is,

$$\begin{array}{rcl} & & \sum _{{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}\frac{2\varOmega }{{(2{\rm{\pi }})}^{3}}{\int }_{{\rm{BZ}}}{d}^{3}k{|{a}_{njlm}(c{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}})|}^{2}{|{a}_{njl{m}^{{\prime} }}(v{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}})|}^{2}\delta ({\varepsilon }_{c{\bf{k}}}-{\varepsilon }_{v{\bf{k}}}-\hbar {\omega }_{{\rm{nuc}}})\\ & & \,\approx \sum _{{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}\frac{2\varOmega }{{(2{\rm{\pi }})}^{3}}{\int }_{{\rm{BZ}}}{d}^{3}k{|{a}_{njl}(c{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}})|}^{2}{|{a}_{njl}(v{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}})|}^{2}\\ & & \,\delta ({\varepsilon }_{c{\bf{k}}}-{\varepsilon }_{v{\bf{k}}}-\hbar {\omega }_{{\rm{nuc}}}),\end{array}$$

(21)

then the summation over m and m′ may be carried out analytically, finally giving

$$\begin{array}{l}{\varGamma }_{{\rm{IC}}}\,\approx \,\frac{{\rm{\pi }}}{3\hbar }\frac{1}{2{I}_{{\rm{e}}}+1}{\langle g||{\mathcal{M}}||e\rangle }^{2}\sum _{njl}{\langle njl||{\mathcal{T}}||njl\rangle }^{2}\\ \,\,\times \,\sum _{{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}\left[\frac{2\varOmega }{{(2{\rm{\pi }})}^{3}}{\int }_{{\rm{BZ}}}{d}^{3}k{|{a}_{njl}(c{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}})|}^{2}{|{a}_{njl}(v{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}})|}^{2}\right.\\ \,\delta ({\varepsilon }_{c{\bf{k}}}-{\varepsilon }_{v{\bf{k}}}-\hbar {\omega }_{{\rm{nuc}}})].\end{array}$$

(22)

We recognize the quantity in the square bracket as the (twice) PJDOS, which counts the number of allowed transitions at energy ħωnuc between the atomic component |njl⟩ of |vkσv⟩ and the atomic component |njl⟩ of |ckσc⟩. In Fig. 3c, we present the most relevant PJDOS. These PJDOS were computed using VASP (see the next section) and use the scalar relativistic approximation of Koelling and Harmon62. To obtain the relativistic PJDOS, we use the procedure developed in ref. 12, that is, for any l > 0, \({|{a}_{n(l-1/2)l}(c{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}})|}^{2}={|{a}_{n(l+1/2)l}(c{\bf{k}}{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}})|}^{2}={|{a}_{nl}|}^{2}/2\), in which |anl|2 is the VASP projection. As a result, for l > 0, the relativistic (njl) → (njl) PJDOS is a quarter of the scalar relativistic value. On the other hand, because the VASP calculation was independent of spin, the double summation over σc and σv in equation (21) results in a factor of 2 × 2 = 4. In Extended Data Table 2, we list the HFI constants A, the corresponding ‘diagonal’ values of the PJDOS at the nuclear energy for various Th atomic states and the contributions to the IC rate. Using these values, we arrive at an estimate for the IC rate of

$${\varGamma }_{{\rm{IC}}}\approx 1.2\times 1{0}^{4}\,{{\rm{s}}}^{-1},$$

(23)

corresponding to an IC lifetime of 80 μs.

In obtaining the estimate in equation (22), we have neglected the contribution from the cross terms in the expansion of \({|{W}_{c{\sigma }_{{\rm{c}}}v{\sigma }_{{\rm{v}}}}^{{\rm{ge}}}({\bf{k}})|}^{2}\). Neglecting off-diagonal HFI matrix elements, the contribution from these terms reads

$$\begin{array}{c}{\varGamma }_{{\rm{I}}{\rm{C}}}^{{\rm{cross\; terms}}}\,\approx \,\frac{{\rm{\pi }}}{3{\hbar }}\frac{1}{2{I}_{{\rm{e}}}+1}{\langle g||{\mathcal{M}}||e\rangle }^{2}\\ \times \sum _{njl\ne {n}^{{\prime} }{j}^{{\prime} }{l}^{{\prime} }}\langle njl||{\mathcal{T}}\,||njl\rangle \langle {n}^{{\prime} }{j}^{{\prime} }{l}^{{\prime} }||{\mathcal{T}}\,||{n}^{{\prime} }{j}^{{\prime} }{l}^{{\prime} }\rangle \\ \times \,\sum _{{{\sigma }}_{{\rm{c}}}{{\sigma }}_{{\rm{v}}}}\left[\frac{2{\Omega }}{{(2{\rm{\pi }})}^{3}}{\int }_{{\rm{B}}{\rm{Z}}}{d}^{3}k{a}_{njl}^{\ast }(c{\bf{k}}{{\sigma }}_{{\rm{c}}}){a}_{njl}(v{\bf{k}}{{\sigma }}_{{\rm{v}}}){a}_{{n}^{{\prime} }{j}^{{\prime} }{l}^{{\prime} }}(c{\bf{k}}{{\sigma }}_{{\rm{c}}}){a}_{{n}^{{\prime} }{j}^{{\prime} }{l}^{{\prime} }}^{\ast }(v{\bf{k}}{{\sigma }}_{{\rm{v}}})\delta ({{\varepsilon }}_{c{\bf{k}}}-{{\varepsilon }}_{v{\bf{k}}}-{\hbar }{\omega }_{{\rm{n}}{\rm{u}}{\rm{c}}})\right].\end{array}$$

(24)

Heuristically, we expect the different terms in equation (23) to have different phases and, thus, their total sum to be small. A more detailed calculation in which the expansion coefficients anjl(ckσc) and anjl(vkσv) are computed explicitly is needed to precisely gauge the accuracy of this approximation. This is the subject of a future work. Here we assume that the expansion coefficients have the same phase (and may thus be taken as all real) and estimate the maximum contributions from the cross terms. In this case, the quantity in the square bracket of equation (23) is a ‘cross-PJDOS’, which is obtained by summing over the delta functions weighted by the product of square roots of |anjl|2. The maximum values for the cross terms are listed in Extended Data Table 3. The sum of these cross contributions amounts to

$${\varGamma }_{{\rm{IC}}}^{\max \,{\rm{cross}}\,{\rm{terms}}}\approx 2.6\times 1{0}^{4}\,{{\rm{s}}}^{-1}.$$

(25)

The estimated maximum IC rate is therefore

$${\varGamma }_{{\rm{IC}}}^{\max }\approx 3.8\times 1{0}^{4}\,{{\rm{s}}}^{-1},$$

(26)

corresponding to an IC lifetime of 30 μs.

A further reduction in the IC lifetime is very plausible if we that the relative error in making the non-relativistic approximation |an(l−1/2)l(ckσc)|2 = |an(l+1/2)l(ckσc)|2 = |anl|2/2 is approximately (αZ)2, that is, about 40% for Z = 90 of Th. Because relativistic contraction generally increases the electron density near the origin, the IC rate including relativistic effects may be larger than its non-relativistic counterpart by a factor of about 1.42 = 2, thus further reducing the estimated IC lifetime to 15 μs.

Computational methods for electronic structure theory

Calculations were performed with VASP version 6.4.2 (ref. 65) using the PAW66 method. The structure of ThO2 was optimized with DFT in the conventional unit cell using the PBE67 functional, 6-6-6 Γ-centred k-mesh and a 500-eV plane wave cut-off. Our computed lattice parameter is 5.617 Å, which matches very well with experimental measurements of 5.597 Å (ref. 68). Subsequent electronic structure calculations used the optimized structure in the primitive cell representation.

Parameters for G0W0 calculations69,70,71, specifically the k-mesh, plane wave cut-off energy and the number of frequency grid points (NOMEGA tag in VASP), were tested for convergence of the bandgap. The k-mesh was tested with a 400-eV cut-off and NOMEGA = 80, the cut-off was tested with a 6-6-6 k-mesh and NOMEGA = 80 and NOMEGA was tested with a 400-eV cut-off and a 4-4-4 k-mesh. The number of unoccupied bands was 812 (there are 12 occupied bands). The results of these tests are shown in Extended Data Tables 4–6. On the basis of these results, further G0W0 calculations were done with an 8-8-8 k-mesh, a 500-eV plane wave cut-off and 80 frequency grid points.

Our converged bandgap of 6.20 eV agrees well with single-crystal and thin-film measurements of 5.9 eV (refs. 42,43), although we note that a range of bandgaps has been reported on the basis of a range of experimental samples (thin films, nanoparticles, single crystals)72,73,74,75,76 because the measured absorption spectrum can be strongly influenced by morphology, defects and the effects of irradiation.

The BSE is a two-particle Green’s function formalism to explicitly account for electron–hole interactions in electronic excited states77,78. The G0W0 + BSE parameters were converged with respect to the predicted absorption spectrum. The tested parameters were the highest excitation energy (OMEGAMAX) and the number of occupied and unoccupied bands (NBANDSO and NBANDSV, respectively) considered in the BSE calculation. Absorption spectra computed with various settings for these methods are shown in Extended Data Fig. 2a,b. On the basis of these tests, further G0W0 + BSE calculations were carried out with OMEGAMAX = 20 eV and (NBANDSO, NBANDSV) = (8, 16).

We can validate our method against published experimental data by computing the dielectric function with G0W0 + BSE. Our computed data, shown in Extended Data Fig. 2c,d, are a good match with the spectroscopic data in ref. 72. Some differences in the imaginary part of the dielectric function ε2, namely the rate at which ε2 increases with increasing energy from 5 to 8 eV and the low-energy non-zero ‘tail’ in the experimental spectrum, we attribute to the presence of defects in the real crystal, as noted by the authors of the experimental study.

We also compute the absorption spectrum of ThO2 with G0W0 + BSE, as shown in Extended Data Fig. 2e. The value at the nuclear transition energy is 1 × 106 cm−1 ≡ 0.1 nm−1, in agreement with ellipsometric measurements35.

Absorption spectra and dielectric functions were processed from VASP output with VASPKIT79.

Isomer shift

The isomer shift originates from differences in the nuclear charge distribution between the ground and excited nuclear states. The value of the shift depends on the local electronic environment of 229Th. Here we follow the formalism40 that combines relativistic many-body atomic-structure methods with periodic DFT to evaluate the isomer shifts in 229ThO2. The scalar relativistic periodic DFT reproduces valence band properties, whereas relativistic atomic-structure methods capture the essential core-electron relaxation effects. The valence band contribution to the isomer shift in 229Th solid-state hosts is expressed as40

$$\delta {E}_{{\rm{iso}}}^{{\rm{VB}}}=\sum _{{\ell }}{{\rm{IPDOS}}}_{{\ell }}\delta {\varepsilon }_{{\ell }}^{{\rm{iso}}}({{\rm{Th}}}^{3+}),$$

(27)

in which IPDOSℓ denotes the integrated projected (on 229Th) valence band density of states for angular momentum ℓ and \(\delta {\varepsilon }_{{\ell }}^{{\rm{iso}}}({{\rm{Th}}}^{3+})\) is the isomer shift for the lowest-energy valence orbitals of Th3+ of angular momentum ℓ. The valence band isomer shift is to be added to the isomer shift in 229Th4+ ions; this contribution remains constant across a wide range of materials. Extended Data Table 7 presents the calculated isomer shifts for 229ThO2 for three different methods. Compared with the PBE and MBJ80,81 methods, the G0W0 method includes self-energy correction and, as discussed earlier, we consider it of a higher quality.

Extended Data Table 8 presents the calculated isomer shifts \(\delta {E}_{{\rm{iso}}}^{{\rm{VB}}}\), the corresponding nuclear clock frequencies ν of 229Th and their offsets Δν relative to the ThO2 reference for a range of solid-state hosts.

Determination of clock stability

We estimate the clock stability by82

$$\sigma =\frac{1}{2{\rm{\pi }}QS}\sqrt{\frac{{T}_{{\rm{e}}}+{T}_{{\rm{c}}}}{\tau }},$$

(28)

in which Q = f0/Δf is the transition quality factor, S is the signal-to-noise ratio, Te is the excitation time, Tc is the electron collection time and τ is the averaging time. As stated in the text, we assume that Δf is dominated by the homogeneous lifetime broadening owing to IC and use Δf = 16 kHz. For our analysis, we assume Te = Tc = 12 μs and a shot-noise-limited signal-to-noise ratio given by \(S=\sqrt{{N}_{\det }}\), in which Ndet is given by

$${N}_{\det }={N}_{{\rm{e}}}\times (1-{{\rm{e}}}^{-{T}_{{\rm{c}}}/{\tau }_{{\rm{IC}}}}),$$

(29)

Ne (≈2.5 × 107) is the total number of 229Th nuclei excited, η = 0.5 is the electron detection efficiency in the clock system and τIC = 12 μs. Ne is calculated assuming that the probe laser linewidth is much smaller than the lifetime-limited transition linewidth, and the probe laser power is 100 μW. From this, we obtain a projected clock performance of about \(2\times 1{0}^{-18}/\sqrt{\tau }\).