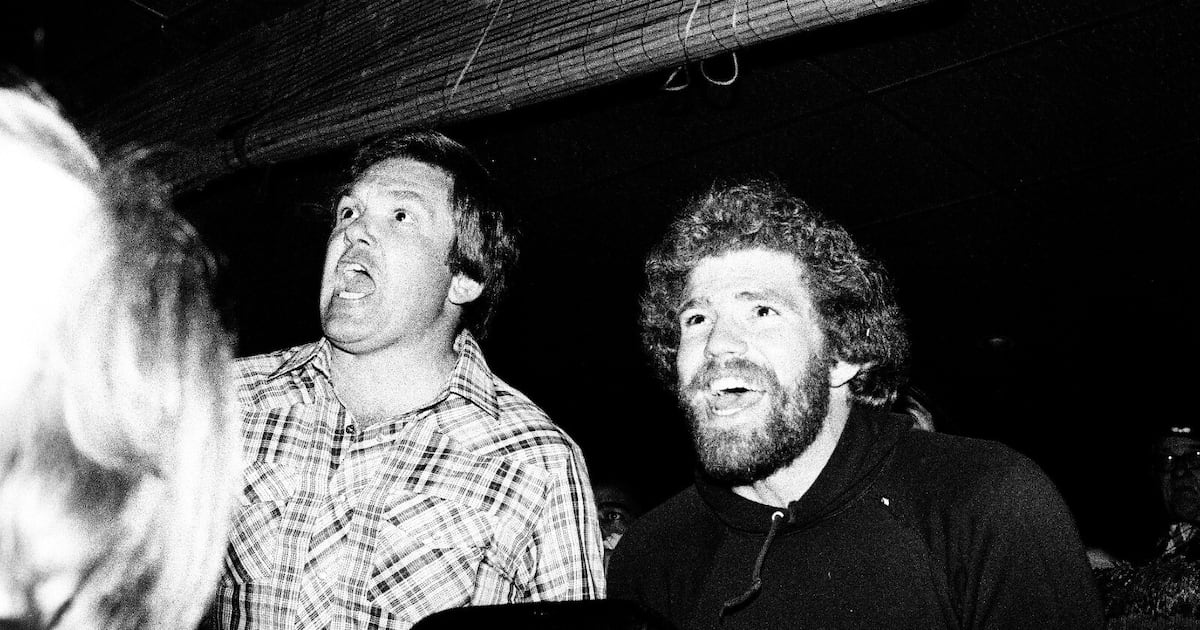

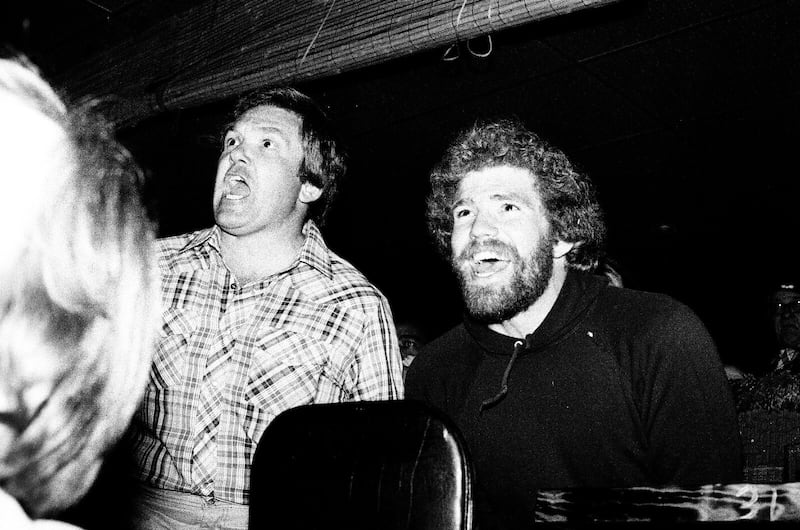

Fans react to boxing action in this photo from June 20, 1980, when the Monkey Wharf bar in Anchorage hosted a night of boxing broadcast by Visions, a subscription TV service. (Photo provided by David Reamer)

Fans react to boxing action in this photo from June 20, 1980, when the Monkey Wharf bar in Anchorage hosted a night of boxing broadcast by Visions, a subscription TV service. (Photo provided by David Reamer)

Part of a continuing weekly series on Alaska history by local historian David Reamer. Have a question about Anchorage or Alaska history or an idea for a future article? Go to the form at the bottom of this story.

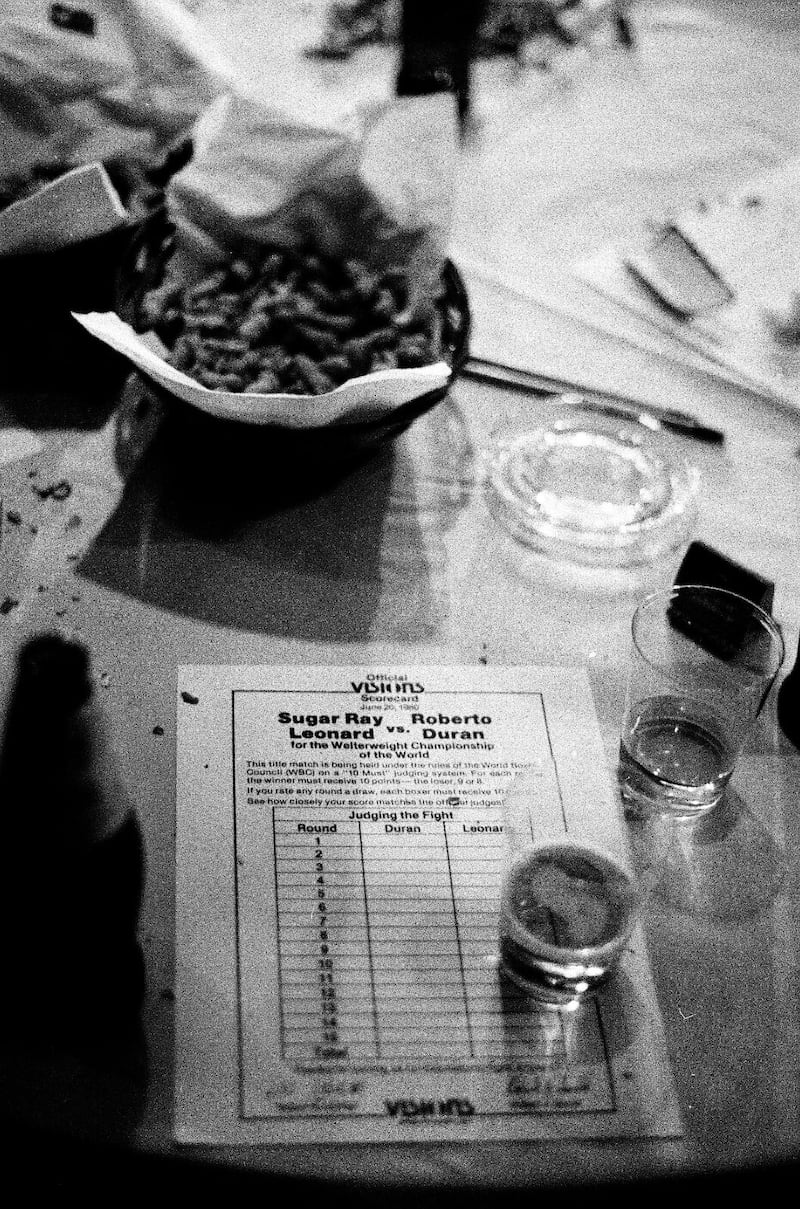

The men shifted their focus back and forth, between the screens, their drinks, and the several attractive young women in shorts. There may have been other women in the crowd, but their presence was overwhelmed by the leers and heavy breaths. Sugar Ray Leonard and Roberto Duran slugged it out in a foreign country, appearing as tiny figures upon the televisions hung on the wall. Visions — that was the word emblazoned everywhere, from the scorecards on the table to signs on the wall and projecting from the tight white T-shirts of the ladies working the event. It was June 20, 1980, just another night in Anchorage. And it all happened at an establishment called the Monkey Wharf.

Recently, I came across a fascinating collection of photographs from this obscure, if illuminating, evening. Together, they mean nothing and everything, all depending on your perspective. There were no deaths, no sudden alteration to life in Anchorage. The only famous people involved were the distant ones flickering on the TV sets. Differently, they are insightful relics, documentation of how people lived then, some people at least. From boxing to premium television to a notorious nightclub, these images are a way of studying the cultural past.

The easiest aspect to explain is boxing. Once upon a time, Anchorage was a boxing-mad town. Former heavyweight champion Sonny Liston fought at the Anchorage Sports Arena in 1966, part of his slow comeback after losses to Muhammad Ali. The once and future champ George Foreman fought at Sullivan Arena in 1988, amid his own comeback story. Multiple bars regularly featured more local-scaled bouts, like Country City in South Anchorage, what had been the Edgewater Motel and is now Anchorage re:MADE. There was also the Pines on Tudor Road.

The Leonard-Duran fight was a highly anticipated matchup between two already legendary pugilists. Leonard was the welterweight champion and Olympic gold medal winner; Duran was the No. 1 contender moving up a weight class after a six-year run as lightweight champion. Their first meeting was promoted as the Brawl in Montreal, which those people in Anchorage were watching that evening at the Monkey Wharf. And those spectators got their money’s worth, as it went the distance with Duran winning by unanimous decision. They fought again that November, a more notorious fight. In the eighth round, Duran turned his back on Leonard and quit, allegedly saying “No más,” meaning “no more” in Spanish.

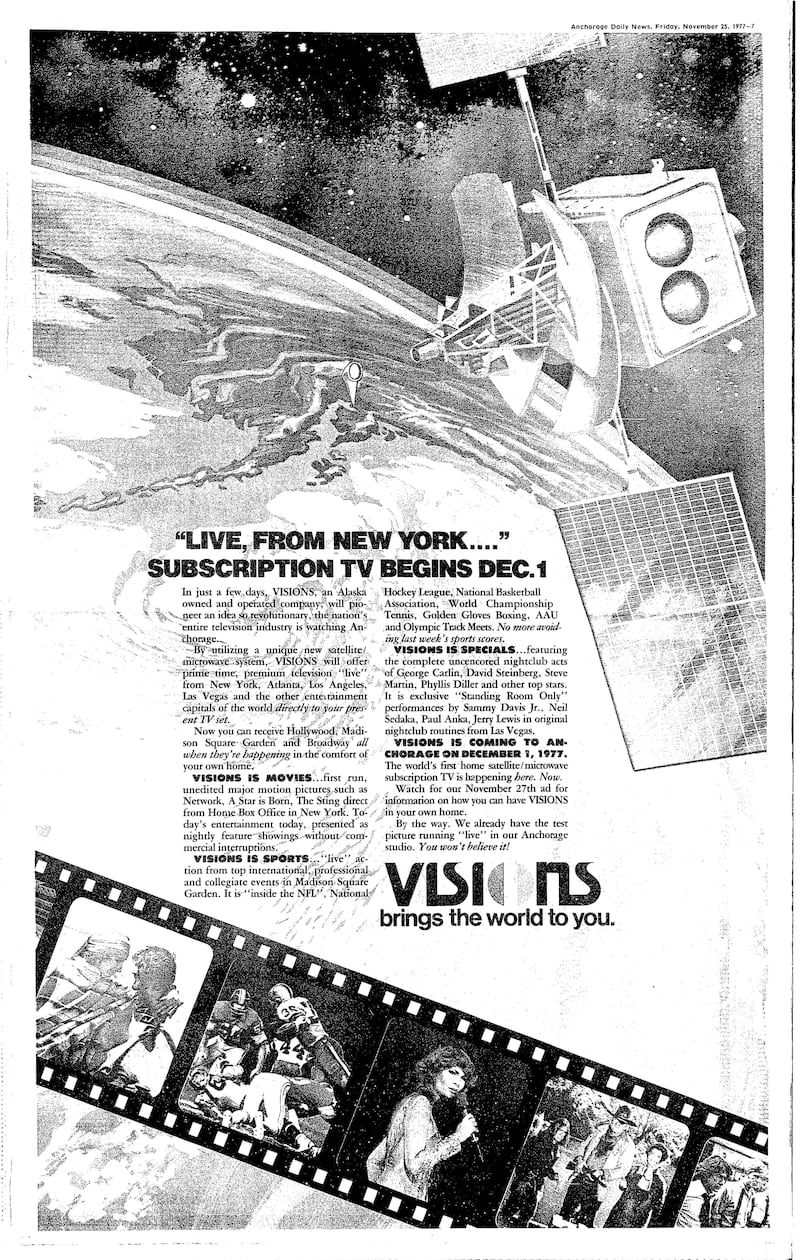

Visions is a slightly more complicated subject, a curious footnote in local entertainment history. Before cable, and long before streaming, there was Visions, the first premium TV channel in Anchorage. It launched on Dec. 1, 1977. For a $72.50 installation fee and $26.50 a month, customers received 24 hours a day of commercial-free programming, including classic movies, live sports, musical specials and an early version of Home Box Office, or HBO. After accounting for inflation, those prices equate to $380 and $140, respectively, in 2025 money. The more tenured residents will recall Visions as Channel 6, its position on the TV dial.

An advertisement that appeared in the Anchorage Daily News on Nov. 25, 1977, for the TV subscription service Visions, which was available in Anchorage in the late 1970s and early ’80s.

An advertisement that appeared in the Anchorage Daily News on Nov. 25, 1977, for the TV subscription service Visions, which was available in Anchorage in the late 1970s and early ’80s.

One of the founding owners, Robert Uchitel, told the Daily News, “Anchorage is a great place to live, but it doesn’t have entertainment. What you get for free is worth exactly that. We’ll have movies that of the same, if not better quality, than what Wometco (movie theaters) brings up … We’ll pick up everything that is good, and put the best on 24 hours a day.”

As cable was then unfeasible for Anchorage, Visions was broadcast via satellite. They installed unique, conical-esque antennas atop subscribers’ homes to receive the microwave signals. In that way, it was easy to drive around town and see who was paying for Visions. Friends and family could hardly lie with the evidence visible on their roofs.

For example, the following is their schedule for Dec. 30, 1977. It began with “The Human Monster,” a 1939 British horror film starring Bela Lugosi. Then there was a live broadcast of an NBA game, the New Orleans Jazz versus the New York Knicks. The Knicks won 118-116. The Jazz moved to Utah in the summer of 1979.

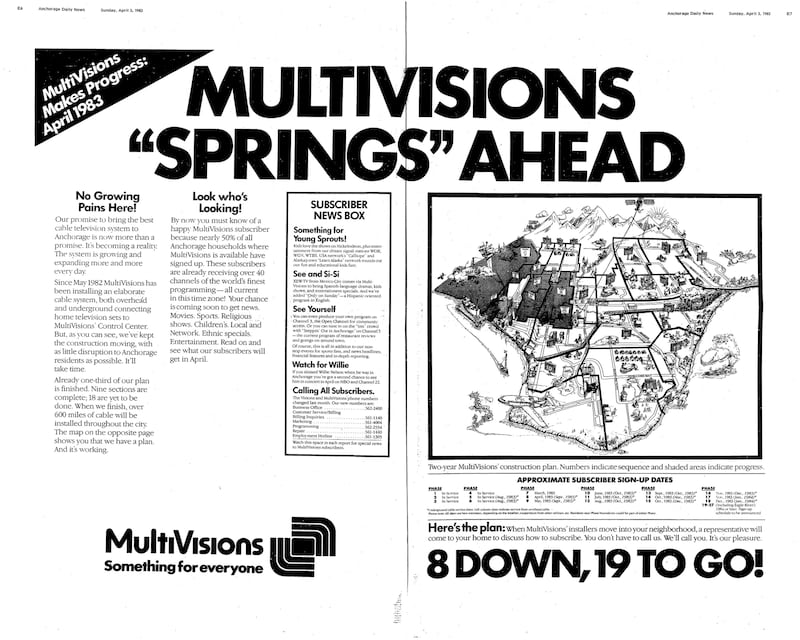

An April 3, 1983, advertisement in the Anchorage Daily News for MultiVisions, a television service offered in Anchorage in the 1980s.

An April 3, 1983, advertisement in the Anchorage Daily News for MultiVisions, a television service offered in Anchorage in the 1980s.

HBO programming ran after the game, beginning with the 1976 movie “Part 2 Sounder,” then an episode of “Inside the NFL.” An eclectic series of movies, like a cinephile’s dream of an afternoon, followed. The coming-of-age drama “Birch Interval” (1976) led to the 1957 French film “Casino de Paris,” which led to the Stanley Kubrick classic “A Clockwork Orange” (1971), which led to the Al Pacino and John Cazale bank-robbery masterpiece “Dog Day Afternoon” (1975). The evening concluded lightly, with the star-studded comedy “Shampoo” (1975). The rest of the day was filled with previously obtained movies and reruns of live events.

Within a couple of weeks, they had 300 subscribers, and the early reviews were positive. Joe Young, an Anchorage police sergeant, disliked commercial television but eagerly signed up for Visions. He told the Daily News, “I hate TV. I think most of the stuff is geared to the mentality of an eight-year-old, and the commercials are geared to the mentality of a five-year-old. Besides, most things on TV are cop shows, and they’re so ridiculous I don’t care to comment.”

And there were other benefits. One customer joked, “My TV has learned swear words and there are naked women running around my living room.” At the end of February 1978, Visions had 1,500 subscribers and a waiting list of a 1,000 more households. With a winter launch, the short days and low temperatures slowed installation.

The Leonard-Duran fight was one of Visions’ most lavish promotional efforts. Elsewhere, in other states, some movie theaters charged as much as $20 to watch the bout. But Visions offered it for free, prompting a wave of new subscribers, including several bars. The Monkey Wharf likely subscribed at this time, as they thereafter promoted live football and baseball via Visions.

In 1979, the Visions parent company, MultiVisions, was awarded the right to provide cable service to Anchorage. They began offering cable to Fort Richardson and Elmendorf Air Force Base in 1980, but legal challenges and technological innovations delayed its introduction to Anchorage proper until 1982. To reduce confusion as much as anything else, Visions was rebranded as Multivisions, though the new name was also more apt as the service expanded to include multiple cable-delivered channels. In April 1983, the company claimed that nearly 50% of all households within their service area were subscribers. Some of those homes included children who quickly discovered the physical hack with those cable boxes, the trick that enabled access to the, shall we say, more mature material.

Sonic Communications bought MultiVisions for $78 million in 1986. The result was a new provider name, Sonic Cable. After another sale, it became Prime Cable in the late 1980s. GCI bought it in 1996 and renamed it GCI Cable in 1997.

A boxing scorecard for a bout between Roberto Duran and Sugar Ray Leonard on June 20, 1980, at the Monkey Wharf bar in Anchorage. (Photo provided by David Reamer)

A boxing scorecard for a bout between Roberto Duran and Sugar Ray Leonard on June 20, 1980, at the Monkey Wharf bar in Anchorage. (Photo provided by David Reamer)

Those readers familiar with Anchorage nightlife in this era have been waiting for this article to get to the good stuff. Everyone else is asking the obvious question, forget about Visions and boxing, what was the Monkey Wharf, and why was it named that? The Monkey Wharf was a club at 529 C St., due east of the 5th Avenue Mall.

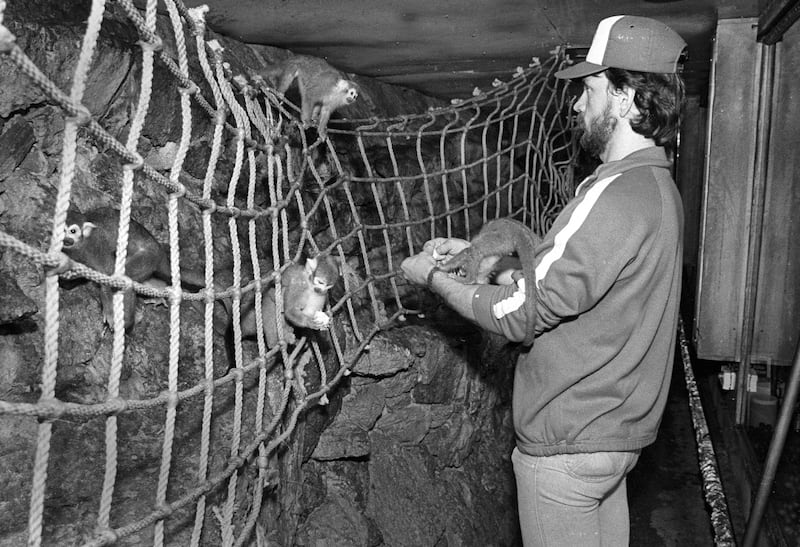

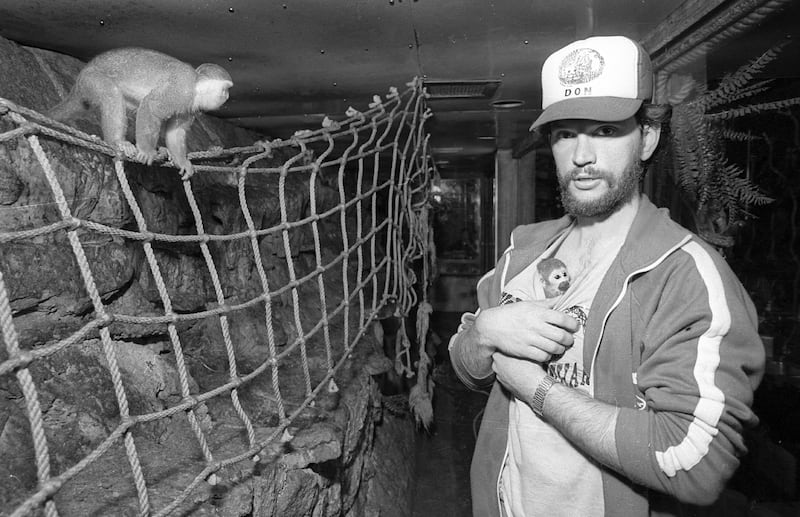

It opened in 1976, a pipeline-era club with everything that cultural shorthand suggests. The name was the Monkey Wharf because there was a glass cage behind the bar filled with a mix of capuchin and squirrel monkeys. In its earliest days, the business emphasized its food, to limited success with the rough crowds that gathered there. Instead, it soon became the place where anything might happen. There was wrist wrestling, magicians like Mike Wong, local bands like Razar, football on Sundays, major league baseball on other days, drugs, fights, so many drunken brawls and innumerable instances of impaired thinking.

The Anchorage-based Razar was something like the house band, a heavy metal ensemble except with a secret identity. Sometimes they performed as the Void Boys, a new wave group with an entirely different sound. They were in their Razar guise when pyrotechnics at the Monkey Wharf set their lead guitarist’s hair on fire, sidelining him for several weeks.

And no, the monkeys did not enjoy the live music experience. They shrieked, taunted and were terrorized by the noise. But again, this wasn’t a drinking establishment for saints even in its best days. In 2002, Anchorage developer Mel Tipton described the monkey cage to the Daily News. “I once opened that cage … and it was a killer. It was the worst odor I have ever smelled.”

The Monkey Wharf was not exactly the most dangerous bar in Anchorage history. To the best of my knowledge, soldiers were never barred from it as they have been at other local dives. Still, the Monkey Wharf’s offenses tended toward the spectacular. In November 1977, the Anchorage Times police blotter included a man charged with assault and battery at the Monkey Wharf after he “reportedly hit a woman with drinking glass while involved in a fight with a hypnotist.” In October 1982, Jerry Billiken was discovered passed out in the alley behind the club. His blood alcohol count was an astonishing .383, and he died without waking.

In March 1983, three men lured another outside from the club. One of them, I kid you not, pulled a sword from a cane. Another revealed an Uzi submachine gun. They robbed their mark of the money from his wallet but were quickly arrested at a nearby gas station, presumably identified for having a sword cane, Uzi and the exact amount of stolen cash in their possession.

Doug Vandegraft is the foremost historian of bars in Alaska and is accustomed to a wide range of drinking establishments. From the roughest to the less rough, the full range of Alaska bars, he’s experienced all sorts. Yet, he was somewhat haunted by the Monkey Wharf.

On his Notorious Bars of Alaska website, he wrote, “The Monkey Wharf was the very first bar that I visited after moving to Anchorage in August of 1983. I recall the aquarium above and behind the bar where a dozen or so small monkeys resided. What I will never forget was observing a table where an older man and two scantily-dressed young women were taking turns indulging in a pile of cocaine. I had never witnessed such a bold violation of the law in such a public place. No one else in the bar seemed to notice except me. I asked my companion, ‘Isn’t cocaine illegal in Alaska?’”

For all things there is an end, even for those shoddy, shadowed halls of iniquity. George LaMoureaux bought the bar in March 1985 with the intent to significantly renovate the pipeline-era relic into a high-end discotheque called the Ritz. There would be waiters in tuxedos and waitresses in slinky, flapper dresses, a different atmosphere entirely from the cocaine and screaming monkeys. Different people have different tastes, apparently.

When most bars or nightclubs close, they do so without public notice. One night, people are drinking and making delightfully questionable decisions. The next night, the door is locked, and memories immediately begin to fade. More often than not, a new bar eventually opens in the same location, with some minor redecorating, maybe or maybe not in time to replace the sign outside. Over the course of a month from 1991 to 1992, a bar on Spenard Road went from the Roxy to the Paragon to the Underground, without enough time for the Paragon to have its own sign.

[Behind the Anchorage Alano Club building, a long history of doomed Spenard bars]

Don Nicholson looked after the monkeys at the Monkey Wharf bar, a roughneck saloon where pipeliners use to elbow up to watch dozens of monkeys play in glass cages behind the bar. (Jim Lavrakas / Anchorage Daily News archive 1982)

Don Nicholson looked after the monkeys at the Monkey Wharf bar, a roughneck saloon where pipeliners use to elbow up to watch dozens of monkeys play in glass cages behind the bar. (Jim Lavrakas / Anchorage Daily News archive 1982)  Don Nicholson looked after the monkeys at the Monkey Wharf bar, a roughneck saloon where pipeliners use to elbow up to watch dozens of monkeys play in glass cages behind the bar. (Jim Lavrakas / Anchorage Daily News archive 1982)

Don Nicholson looked after the monkeys at the Monkey Wharf bar, a roughneck saloon where pipeliners use to elbow up to watch dozens of monkeys play in glass cages behind the bar. (Jim Lavrakas / Anchorage Daily News archive 1982)

For the glaring reason, the Monkey Wharf was a more complicated renovation: the monkeys. LaMoureaux offered them to the Alaska Zoo, and a local civic organization volunteered to pay for a monkey house. The zoo declined, claiming the tropical-originating monkeys did not belong in a zoo featuring Alaska animals. Instead, the poor animals were gifted to the Cabbage Inn, a restaurant in Kenai. From there, they exit documented history. However, an off-the-record source claims the monkeys froze to death because a heater was left off during that first winter. For whatever reason, they disappear.

The dream of a glitzy Ritz lasted only a little longer. Some ghosts or vibe of the old Monkey Wharf lingered. Fights, armed and not, were common. In October 1985, a patron was stabbed in the adjoining parking lot. All customers were scanned with a metal detector on their way in, the first Anchorage club with that requirement. It was billed as the “1920s Nightclub,” but it was just more 1980s Anchorage. In seemingly every political discussion about Anchorage or Alaska, there will be people who claim crime is a relatively recent innovation, the fault of recent administrations. How quickly they forget the oil money heyday, a period of rampant drugs and vice, when Fourth Avenue was commonly referred to as Skid Row.

The Ritz closed in early 1986 only to reopen as a strip club, still “very sophisticated” per LaMoureaux. The waitresses wore short, sequined camisoles, bow ties, cuffs and a G-string while serving drinks, otherwise nothing at all. You know, classy stuff. That December, the theme changed again. Out went stripping, and “The Ritz” was suddenly a country bar, a dazzling exercise in dissonance. It shockingly closed a few short months later.

The building sat empty for several years before being torn down. For years after that, the site was part of an empty lot, lined with flowers in the summer. In 2002, the National Park Service bought this larger lot, with their new building completed there in 2003.

Boxing, satellite television and a bar featuring monkeys: This is the history not as people perhaps desired, but the one they chose and actually lived. As in, Anchorage in the early 1980s was the sort of town where a place like the Monkey Wharf could exist in all its infamy, a lesson for sure.

Key sources:

Bennett, Ed. “Trooper’s ‘Drivin 55’ Spots Are Appealing and Effective.” Anchorage Daily News. June 21, 1980, G6.

Campbell, Larry. “Club Owners Try to Keep Trouble Out.” Anchorage Daily News. October 17, 1985, A-1, A-16.

Erickson, Jim. “Multivisions Sold for $78 Million.” Anchorage Daily News. March 28, 1986, C-6.

Hopfinger, Tony. “Downtown Lot May Go to Park Service.” Anchorage Daily News. May 23, 2002, F-1, F-6.

Hunter, Don. “Bar Owner Hoping Monkeys Reprieved.” Anchorage Daily News, April 7, 1985, B-1, B-3.

Hunter, Don. “Cable Rights Awarded.” Anchorage Daily News. September 22, 1979, A-1, A-10.

Jones, Stan. “Pay TV Firm Wires City.” Anchorage Daily News. June 22, 1982, C-2.

Killoran, Nancy. “Monkeys Will Go to Kenai.” Anchorage Times. April 9, 1985, A-1, A-10.

McCoy, Kathleen. “Alaska Rock: 5 Nuggets of Local Talent.” Anchorage Daily News. October 21, 1982, F-10.

Multivisions advertisement. Anchorage Daily News. April 3, 1983, E6-E7.

Nightingale, Suzan. “TV Visions: ‘Network’ and Night Clubs.” Weekend and Television Guide insert, Anchorage Daily News. December 17, 1977, 1A-2A.

“Pay-TV Firm to Start Here.” Anchorage Daily News. October 19, 1977, 1, 2.

“Police Blotter.” Anchorage Times. November 29, 1977, 45.

“Police Report.” Anchorage Daily News. March 31, 1983, B2.

Postlewaite, Susan. “Sonic Cable Finds a Buyer; Price Exceeds $130 Million.” Anchorage Daily News. October 14, 1988, A-1, A-10.

Shallit, Bob. “Cable Start-Up Nears.” Anchorage Daily News. August 22, 1981, E-1.

Shallit, Bob. “Multivisions Begins Service—Quietly.” Anchorage Daily News. September 30, 1980, A-8.

Swift, Earl. “The Ritz to Reopen as Strip Club.” Anchorage Times, March 12, 1986, B-1, B-2.

Vandegraft, Doug. A Guide to the Notorious Bars of Alaska, Revised 2nd Edition. Kenmore, WA: Epicenter Press, 2014.

Vega, Richard L. “From Satellite to Earth Station to Studio to S-T-L to MDS Transmitter to the Home; Pay Television Comes to Anchorage, Alaska.” Telecommunications Systems, Inc., 1978.