Don’t let mortgage woes land you in the mortuary (© fizkes – stock.adobe.com)

People Struggling With Money Problems Face 60% Higher Death Risk

In A Nutshell

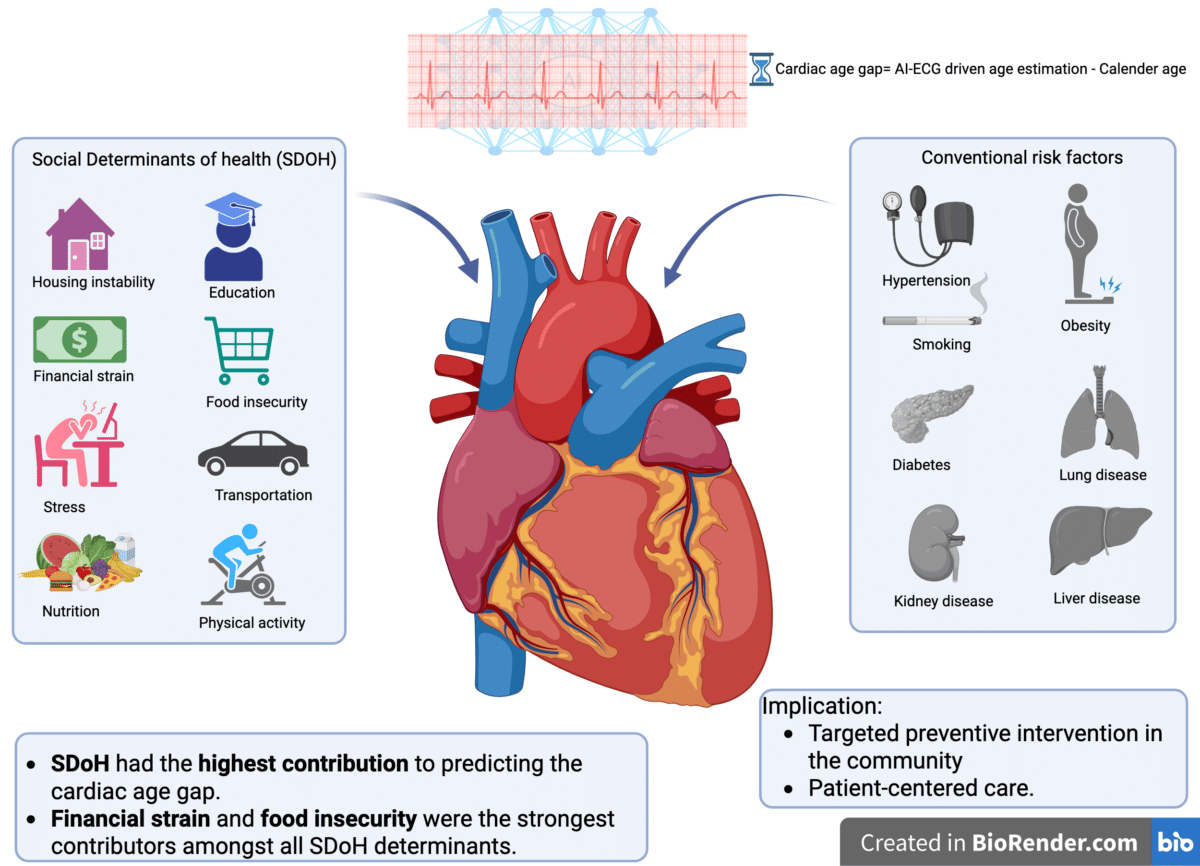

AI analysis of nearly 300,000 electrocardiograms found that financial strain showed the strongest association with accelerated cardiac aging among nine social factors examined, even outweighing some traditional medical risk factors.

People reporting financial struggles faced 60% higher death risk over two years, a stronger association than having had a previous heart attack, which showed only 10% increased risk in the same study.

Food insecurity ranked second among social determinants linked to faster heart aging, while housing instability increased mortality risk by 18%, highlighting how economic factors affect cardiovascular health.

The findings suggest doctors may need to screen patients for financial strain and food insecurity alongside traditional risk factors like cholesterol and blood pressure to identify hidden cardiovascular risk.

Money troubles and financial stress appear linked to an older heart based on AI analysis of standard electrocardiograms. The study behind these findings encompassed nearly 300,000 adult patients seen at Mayo Clinic sites between 2018 and 2023. Financial strain emerged as the most powerful social factor associated with cardiac aging—showing stronger links in mortality analyses than some familiar clinical risk markers.

Mayo Clinic researchers analyzed 280,323 patients using artificial intelligence to estimate biological heart age from electrocardiograms. When they mapped how different factors contributed to the gap between someone’s cardiac age and chronological age, financial resource strain topped the list among nine social determinants examined. Struggling to pay for basics like food, housing, medical care, and heating was associated with measurable differences in heart health independent of traditional risk factors.

AI Reads Your Heart’s Real Age

The technology works by analyzing standard ECG readings to estimate how old your heart actually is, regardless of your birth certificate. Trained on nearly 775,000 ECGs, the AI spots subtle electrical patterns that reveal accelerated aging. Someone whose heart reads electrically “older” faces higher risks of heart disease and death. Study participants averaged nearly 60 years old and were evenly split between men and women. Researchers assessed nine social factors through questionnaires covering stress, physical activity, social connections, housing stability, finances, transportation, food security, nutrition, and education.

Financial Stress Shows Up in Survival Rates

Over two years of follow-up, financial struggles increased death risk by 60 percent after accounting for medical conditions. For context, having had a previous heart attack increased death risk by just 10 percent in the same analysis. Housing instability raised mortality risk by 18 percent. Food insecurity ranked second among social factors associated with how fast hearts age biologically.

Both women and men showed the same pattern, with financial strain and food insecurity topping the list. Among actual medical conditions, high blood pressure showed the strongest connection to accelerated heart aging, followed by diabetes, heart failure, and kidney disease.

A novel analysis investigating the contribution of social determinants of health (SDoH) to cardiac aging has found that financial strain and food insecurity are the strongest drivers of accelerated biological aging and increased mortality risk. The study in Mayo Clinic Proceedings underscores the complexity and interplay of novel social risk factors that may contribute to cardiovascular events and emphasizes the need for targeted preventive interventions and patient-centered care. (Credit: Nazanin Rajai, MD, MPH)

Why Economics May Affect Heart Health

The research, published in Mayo Clinic Proceedings, challenges medicine’s traditional focus on cholesterol, blood pressure, and blood sugar while largely ignoring living conditions. When researchers compared everything together, social factors collectively showed stronger associations with cardiac aging than medical diagnoses did.

Financial stress likely affects hearts through multiple routes. Chronic worry triggers inflammation and hormonal changes that damage blood vessels over time. Economic strain also limits access to nutritious food, delays doctor visits, and makes filling prescriptions harder. Someone who can’t afford fresh vegetables relies on cheaper processed foods. Housing instability disrupts sleep and medication routines.

Racial Gaps Linked to Social Circumstances

African American participants showed faster cardiac aging compared to White individuals even after accounting for medical conditions. This aligns with documented gaps in heart disease rates and life expectancy between racial groups. Previous research has found that predominantly Black neighborhoods, especially historically redlined areas, show worse cardiovascular health markers. The current findings suggest social factors may explain part of these disparities rather than biological differences alone.

The findings point toward a new approach to heart disease prevention. Doctors currently screen for traditional risk factors during checkups. Adding questions about financial strain and food security might identify people at high cardiovascular risk that standard medical tests would miss. Helping patients secure stable housing and adequate nutrition could deliver heart health benefits comparable to managing cholesterol or blood pressure.

Disclaimer: This article is for informational purposes only and is not a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. The research discussed represents observational associations and does not prove that financial strain directly causes heart aging. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified health provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition. If you are experiencing a medical emergency, call 911 immediately.

Paper Summary

Limitations

The study captured data at single points in time rather than following participants over years, limiting conclusions about how social circumstances and cardiac aging change together. The AI-ECG algorithm was validated within Mayo Clinic’s system, so results may not directly transfer to other healthcare settings or populations. Most participants self-identified as non-Hispanic White (86.3%), restricting how findings apply to more racially and ethnically diverse populations. The researchers could not differentiate between cardiovascular and non-cardiovascular causes of death since specific cause-of-death data was unavailable. Patients excluded due to missing ECG data or those whose ECGs were used in training the AI algorithm could introduce selection bias. The cross-sectional design means the study shows associations but cannot prove that financial strain directly causes accelerated cardiac aging, only that the two occur together.

Funding and Disclosures

Drs. Zachi Attia, Paul A. Friedman, and Francisco Lopez-Jimenez are co-investigators of the AI-ECG age algorithm, which has been licensed to Anumana by Mayo Clinic. All other authors reported no potential competing interests.

Publication Details

Rajai N, Medina-Inojosa BJ, Mahmoudi Hamidabad N, Medina-Inojosa JR, Lewis BR, Sara JD, Nyman M, Attia Z, Lerman LO, Friedman PA, Lopez-Jimenez F, Lerman A. Interplay of Social Determinants of Health and Traditional Risk Factors in Predicting Cardiac Aging. Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 2025;100(12):2128-2139. DOI: 10.1016/j.mayocp.2025.01.024

Author affiliations include the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine, Division of Epidemiology in the Department of Quantitative Health Sciences, Division of Clinical Trials and Biostatistics, Division of General Internal Medicine, and Division of Nephrology and Hypertension at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota.