Songwriters living in ancient Egypt would never have expected the words and melodies they sung would feature on Australian music charts 1,800 years later.

But one Australian academic’s obsession with a fragment of a document found in an old Egyptian rubbish heap has helped to share an ancient song with the world.

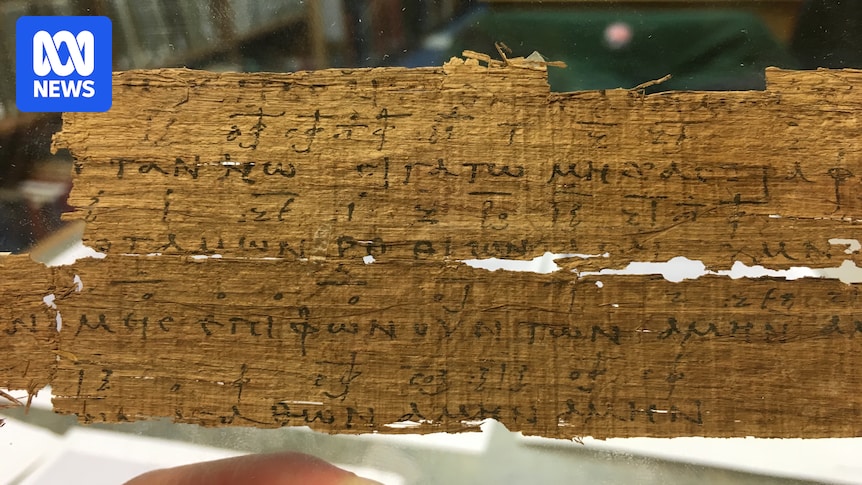

The document known as Papyrus P. Oxy. XV 1786 (P. Oxy 1786) was found amongst thousands of other fragments of documents in the 19th and 20th centuries — a contract to rig a wrestling match, a corn contract, a Roman arrest warrant for a Christian and the front page of Mark’s Gospel from the Bible — in Oxyrhynchus, Egypt.

P. Oxy 1786 is the oldest known Christian song with musical notations on the manuscript.

The moment Professor John Dickson saw it he knew it needed to be shared with the world.

“I’m looking down the microscope at that particular item and literally, in a rush of blood to the head, I thought ‘why has no one brought this back to life and given it back to the world?'” Dr Dickson said.

Dr Dickson said there were about 60 examples of ancient Greek music from 400BC to 300AD, but this was the only Christian example.

John Dickson said the project combined his three loves of ancient history, music and the Christian faith. (Supplied: The First Hymn)

In that moment, a decade ago, he dreamt of resurrecting the song to be sung by modern churches.

And he dreamt of filming the entire process to create a documentary.

A translation of P. Oxy 1786:

Let the world be silent Let not the stars shine their lights

Calm the winds, silence the rivers

Let all praise the Father, the Son and the Holy spirit

Let all sing together Amen, Amen.

Let kings bow, and God receive the glory!

The sole giver of good things, Amen Amen.

The idea, though deemed “outlandish” by his colleagues, stuck with Dr Dickson.

He visited P. Oxy 1786 on every trip to Oxford and “sort of became friends with it”, he said.

Three years ago he committed to making his dream a reality.

Returning to the crypt

During the filming of the documentary Dr Dickson visited Oxyrhynchus, now just an archaeological ruin.

“We wanted to go to where this thing was found and where this song was sung,” he said.

Dr Dickson said singing the original song in Oxyrhynchus was like bringing the hymn home. (Supplied: The First Hymn)

In an underground crypt of the oldest ruined church in the city, Dr Dickson impulsively broke out into song, singing the original Greek song in the original melody.

“I had this overwhelming sense that I was bringing their song back to a place where this song hasn’t been heard for 1,800 years,” he said.’Ancient meets modern’

Dr Dickson asked musician Ben Fielding to resurrect the ancient hymn for modern churches.

With Dr Dickson as their cheerleader and using his translation from the original Greek, Mr Fielding and American musician Chris Tomlin attempted to bring the song back to life.

Mr Fielding would play with different melodies and record snippets on his phone as voice notes. He’d send those voice notes to Mr Tomlin in Nashville.

Operating in different time zones on opposite sides of the world, the musicians worked to reconstruct the ancient tune, keeping the joyful gravitas of the original music.

Musicians Chris Tomlin (left) and Ben Fielding (centre) play their adaption of the hymn for John Dickson. (Supplied: The First Hymn)

“It was a collaborative approach that was very unconventional,” Mr Fielding said.

“Ancient meets modern.

“The challenge we had as song writers is to take something that is ancient and make it attractive to a modern listener or church goer … but the other side of that is to do justice to the original hymn-writers and the hymn itself.

“We wanted to see the modern church sing the song and make those words their own.”

Australian musician Ben Fielding performed The First Hymn for the first time in front of 12,000 people at a performance in Texas. (Supplied: The First Hymn)

The musicians performed the song, called The First Hymn, for the first time publicly at a concert in Texas with 12,000 people.

“To watch the response in the room the first time people were hearing this reinterpretation — resurrection, if you like, of this ancient hymn — was really amazing,” Mr Fielding said.

“The whole room was singing. We walked off the stage and went ‘oh wow. There’s something special here.'”

He hopes the song inspires and unifies the modern church.

“Our singing and our songs have the ability to connect us to something and to people that we may never get to meet,” he said.

“But there are people all around the world that are singing the same songs that we sing and are sharing the same faith that we share, and I think that’s a really beautiful thing.”

A dream realised

Standing out of sight side of stage during that first performance, Dr Dickson wiped a tear from his eye.

“Those people who composed this song and first sang it could never have imagined that the song would come back to life, that there would be 10,000 people joining in the singing of words they wrote,” he said.

“That was the feeling — a connection with whoever the original composers were.

“We wanted a modern melody that could be sung by churches today just as that thing was sung by churches nearly 1,800 years ago.”

A crowd of 12,000 people singing The First Hymn was a dream come true for Dr Dickson. (Supplied: The First Hymn)

He said the song contained core Christian theological doctrine that predated church denominations, and that was encouraging for modern day believers.

“The song was composed in a period when the Romans were really giving the church a hard time,” Dr Dickson said.

“Yet here is a song full of confidence and joy and celebration in the midst of what must have been hell for those early Christians.

“For me there’s a personal desire to be that kind of Christian — one that can bear pressure and unbelief and criticism with good cheer.”

‘Slightly nuts’ response

The song reached as high as the top four most sung songs on a Sunday at churches across Australia according to online library licenser SongSelect.

Dr Dickson said the documentary’s reception had been “slightly nuts”.

It was initially released at 120 cinemas around the country for just one week. It performed so well that major cinemas extended it for another week, twice.

“I’m sure [the cinema companies] were surprised a history documentary that focused on Christianity got so many people out,” Dr Dickson said.

“I don’t think many people in the film industry think that’s something people want to see.”