Early January often appears to be a quiet time for Formula 1 people — drivers, bosses, engineers, mechanics, journalists, and fans — but behind the scenes a lot is going on. In that sense it is a bit like the hush in a theatre just before the curtain rises. Moreover, for one of F1’s 22 race drivers, tomorrow will resonate with meaning, for January 7 is Lewis Hamilton’s birthday. He will be 41, astonishingly, and he is readying himself to embark on his 20th F1 season. Yes, here we are, contemplating a driver who made his F1 debut in 2007 and is in 2026 girding his loins to do battle with men who were babies when he first started a grand prix. Indeed, one of them, Arvid Lindblad, was not yet born. That alone tells you something profound about Hamilton: about his strength, his mettle, his perseverance, and his refusal to be defined by expectation, convention, or precedent.

I have known Lewis for a long time. We overlapped at McLaren between 2008 and 2012, years of glory and tumult, of passion and brooding, of relentless pressure and extraordinary performance. I saw close-up how he worked, how he thought, how he absorbed the slings and arrows that F1 fires so casually and so often at its leading men. I saw the public figure and the private individual, the superstar and the young man trying to make sense of a sport that gives lavishly with one hand and takes mercilessly with the other. So when I say that Hamilton is an all-time great of F1, I do not say it lightly, nor as an exercise in hyperbole, nor as a nod to either received wisdom or fashionable consensus. I say it because I have watched his greatness being forged, lap by lap, race by race, season by season, triumph by triumph.

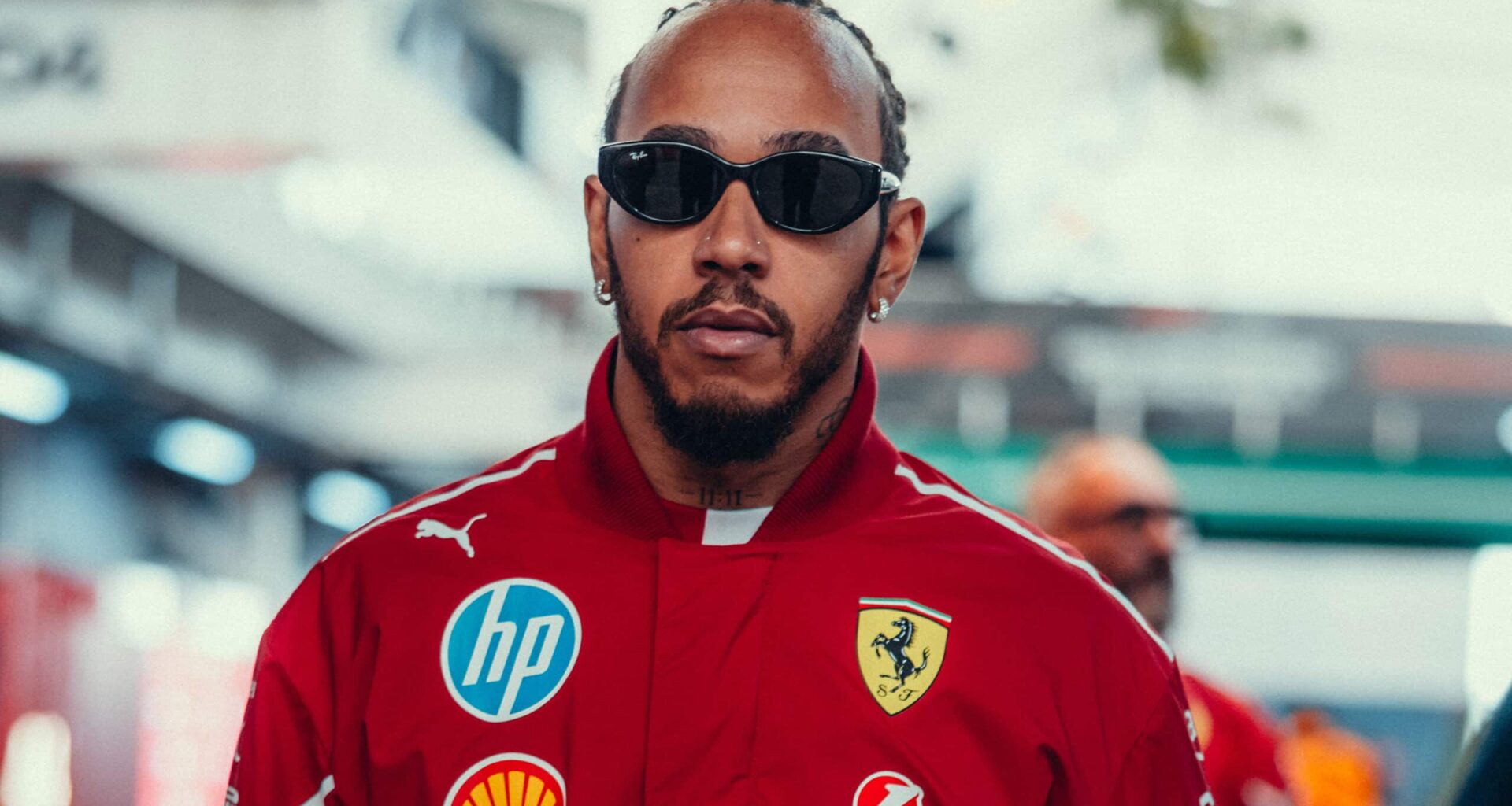

Ferrari promises everything but guarantees nothing

Greatness in F1 is not merely a function of statistics, although Lewis’s numbers are so stratospheric that they almost defy comprehension: seven F1 drivers’ world championships, 105 F1 grand prix wins, 104 F1 grand prix pole positions, 202 F1 grand prix podiums. Those are the bare bones, the cold data, the lines in the record books. But greatness is also about context, about quality of opposition, about adaptability across eras, about a driver’s ability to raise his game when the stakes are highest and the margins thinnest. Lewis has done all of that, repeatedly. He has won with different teams, different cars, different engines, different team-mates, different regulations, and different pressures. He has beaten world champions and would-be world champions. He has won in the dry and in the wet, from the pole and from the midfield, with serene control and with ferocious audacity.

Yet, for all that, he now finds himself at a career crossroads, and it would be disingenuous for us to pretend otherwise. As I say, he will turn 41 tomorrow, and in 2026 he will embark on his 20th F1 season, his second with Ferrari, the most mythos-laden team in the sport’s history, a team that promises everything but guarantees nothing. I dearly hope that the 2026 Ferrari will be a car worthy of his talent, ambition, and legacy. I would love nothing better than to watch him win races in rosso corsa, and to see him add to his already unparalleled magnum opus with a late-career flourish that would have Enzo Ferrari grinning from ear to ear in whatever celestial paddock he now inhabits.

But hope, in F1, is a fragile currency, and realism demands that we acknowledge the doubts and worries about Hamilton that pervade the paddocks, the pitlanes, the press rooms, and the grandstands. In a nutshell, it is possible that he may not be quite as scintillatingly quick as he once was – and, perhaps corroborating that unhappy thesis, we have to concede that in 2025, which in his defence was his first season with the infamously opaque Scuderia, he was comprehensively outperformed by his team-mate Charles Leclerc, who, although he has started 171 F1 grands prix, is 13 years his junior. Worse, Lewis often seemed bewildered by his own underperformance, and his descriptions of it were sometimes not only self-critical but also defeatist.

Hamilton in Baku, where he only managed to qualify 12th on the grid

Grand Prix Photo

Ferrari is Ferrari, glorious and exasperating in equal measure. It can build a masterpiece then trip over its own shoelaces. It can outthink the grid one weekend then outthink itself the next. It is set in its ways: it rarely bends its culture to suit the preferences of an incoming megastar, especially one whose age dictates that such bending might have to be undone, or at least adapted, before too long. The 2026 regulations will usher in a new technical era, and, while that offers opportunity, it also magnifies risk. Insiders, pundits, and fans all harbour the fear that the car that Lewis will drive in his 20th F1 season may not be the one he deserves, and may not therefore allow him to express his genius as he once did with such majestic regularity. And time waits for no man, and no driver, not even one as supremely gifted and as obsessively fit as Hamilton.

Or, to put it another way, we who respect and admire Lewis are becoming troubled by the spectre that no one who loves our sport, and who loves Lewis, wants to see: the possibility that his F1 career might peter out unimpressively, as Michael Schumacher’s did after his injudicious return to F1 with Mercedes in 2010, 2011, and 2012. The old gunslinger, the colossus of his era, came back ever so slightly diminished when, also aged 41, in Bahrain in 2010 he rode back into town after a three-year layoff. He was not diminished in courage or commitment but in out-and-out sharpness, and the sight of him being serially outqualified, outraced, and outpointed by his much younger team-mate Nico Rosberg was painful for those of us who had witnessed at first hand just how brilliant he had been in his prime. It did not tarnish his F1 greatness, but it complicated his F1 narrative, for it added an unnecessary and regrettable coda. Now, many in F1 fear, quietly and reluctantly, that Lewis could be facing a similar fate, not because he lacks ability, but because the sport is unforgiving, because its variables are numerous and perplexing, and because Ferrari still appears to be a few seasons away from achieving technical, operational, and political equilibrium.