Explosive increases in rents and housing prices, a shortage of available apartments and subsidy schemes that tend to exacerbate rather than improve the situation. The number of Greeks who find themselves excluded not only from the homeownership market but even from renting – at least in the area of their choice – continues to grow, and the housing crisis is fast becoming a social one. Making ends meet grows harder and harder, with a disproportionate burden falling on one segment of society, renters, thereby deepening social inequality.

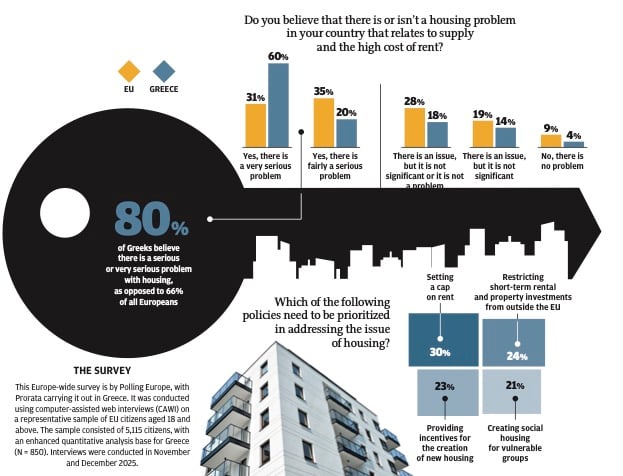

A Europe-wide survey by Polling Europe, published exclusively by Kathimerini, shows how the issue of housing has emerged as a major social challenge and will very likely be the number one economic and political issue the government will have to deal with in 2026 and in the years after that. Across the European Union as a whole, 66% of citizens believe that there is a fairly or very serious problem with housing. In Greece, the issue is perceived as even more severe, with 80% of citizens believing housing to be a very or fairly serious issue, placing the country first in the relevant ranking among EU member-states.

A combination of factors – such as the prolonged economic crisis, followed by the energy crisis and the rising cost of living, the boom in tourism, the reduction in available housing stock, and changes in lifestyles and the social model – has created a perfect storm, pushing Greece to the top spot in the EU in terms of relative housing costs.

How we got here

Greece lies at the epicenter of the crisis, with data from Eurostat showing that it has by far the highest relative housing costs in the European Union. On average, households in Greece spend approximately 36% of their disposable income on housing, against an EU average of 19%. In urban centers, meanwhile, roughly one in three Greeks spends more than 40% of their income on housing-related expenses, including not only rent or mortgage payments, but also electricity, heating, water and other utilities. And this is at a time when Greece’s urban housing stock is relatively limited and low in quality.

A high rate of homeownership in Greece managed to somewhat soften the profound impact of the austerity during the economic crisis and to maintain social cohesion, so, how did we get to where we are today, within just a few short years?

The first reason is rather obvious, as it has to do with the massive drop in incomes, which left Greek households poorer today than they were in 2009, says Angelos Seriatos, the scientific director of Prorata, the company that carried out Polling Europe’s survey in Greece.

“Between 2009 and 2014, Greeks lost more than 40% of their disposable income. And while overall – after a period of relative recovery – the average European has seen their disposable income increase by 22% in the past 20 years, in Greece and Italy, it has shrunk by 5% and 4% respectively. At the same time, as the number of tourists visiting the cities and islands of these particular countries continues to rise constantly, property owners – in Greece during the crisis especially – found new ways to exploit their real estate assets, such as through short-term rentals, thus affecting prices and rental rates in turn.”

Nikos Vettas, the general director of the Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (IOBE) and a professor at the Athens University of Economics and Business, notes that the construction of new residential units and renovation of older ones basically ground to a halt during the debt crisis and have only started recovering in recent years, but without managing to make up the shortfall. “Residential property and construction no longer account for the exceptionally large share in the overall investment mix they had before the crisis, while there’s also a significant shortfall in the labor required to deliver the construction activity that is needed right now.”

Vettas goes on to note that “the country’s population has also dropped significantly, while the number of independent households – at least in urban centers – has risen at the same time, greatly intensifying pressure on smaller-sized homes. In addition, construction costs have risen sharply in recent years due to higher energy and financing costs, as well as labor shortages. This has occurred at a time of substantial needs for the renovation of housing stock that is now several decades old, while the administrative burden in the real estate market and in property transfers remains high, creating delays and distortions.”

According to Ilias Nikolaidis, content director for the Dianeosis think tank, one of the key issues is the way Greek cities are built, with small-scale and highly fragmented homeownership hampering the ability to carry out coordinated, large-scale interventions. “Greek cities were developed in a very fragmented manner after the war, and there has never been a substantial state intervention in housing,” he notes. “We had a weak housing policy, which was further weakened by the crisis (the Workers’ Housing Organization was shut down in 2014). At the same time, property values fell sharply, making real estate increasingly attractive to foreign investors as the crisis unfolded and tourism expanded from 2015 onward, further driving up prices.”

New incentives

According to the Polling Europe survey, 27% of EU citizens believe that the introduction of caps on rent is a top priority. A further 24% call for incentives to encourage private individuals to build new homes, while an equal share support the creation of social housing programs for vulnerable groups. Meanwhile, 16% believe that short-term rentals and real estate investments from outside the EU should be restricted. Policies aimed at managing and addressing the housing issue are also linked to voters’ electoral preferences: Supporters of the left, the greens and the social democrats show stronger support for rent caps and the expansion of social housing programs, whereas center-right and conservative voters favor incentives for private-sector housing construction as a way to boost supply.

In Greece, 30% of respondents favor rent caps, 24% support restrictions on short-term rentals, 23% prioritize incentives for the construction of new housing and 21% favor social housing solutions.

The head of Greece’s tenants’ association (PASYPE), Angelos Skiadas, argues that the introduction of rent caps – that is, a maximum allowable rent based on specific criteria – is the primary measure that can provide relief to tenants, especially if implemented for a period of three to four years, until other long-term measures begin taking effect. He also argues that it is essential to extend the minimum duration of leases from the current three years to six. The time frame is not arbitrary: Six years corresponds to the period a child needs to complete elementary school or middle and high school without being forced to change schools.

He says that a subsidy introduced by the government corresponding to a month’s worth of rent has done “nothing.” “Instead, it is pushing rates to further increases. When owners hear that one month of rent is subsidized, they ask for a higher rate.” Meanwhile, restrictions on the Airbnb regime have also not made much of a difference so far, he says, and will not unless they are combined with a rent cap, since owners pulling their properties off the short-term rental market simply put them on the long-term market at very high rates because they want to recoup any investments they have made.

“The major imbalances cannot be righted overnight,” says Vettas. “But they can be mitigated through short-term interventions to ease pressure on the areas and households facing the most acute problems, and then addressed more substantively in the medium term by strengthening housing supply and improving adaptability to changing demand.”

Far-right fodder

The issue disproportionately affects people who live in rented housing and clearly also has an impact on the country’s other major challenge: demographics. “The cost of housing is leaving Greeks with very little real room to invest elsewhere, to create a family, to lead a normal life,” says Nikolaidis.

According to Seriatos from Prorata, the problem of affordable housing has evolved into a top-tier social issue, sparking reaction and demands for a Europe-wide strategy. The European Commission took another step in this direction in December 2025 with the introduction of the European Affordable Housing Plan, which provides funding for social and affordable housing and prioritizes the issue within the new fiscal framework. At the same time, national policies such as – which entails restrictions on short-term rentals, tax incentives for long-term leases, rent regulation and the use of public land for social housing – or the Netherlands’ ambitious target of building 900,000 new homes by 2030, demonstrate that housing is an issue governments are actively addressing.

“Reality shows that without strong public policy, investment in social housing and strict rules on short-term rentals, the crisis will intensify,” notes Seriatos, emphasizing the need for deep structural changes, “especially given the looming risk of further growth of the far-right, which appears fully ready to exploit this crisis as well, by proposing simplistic solutions cloaked in intolerance.”

Indeed, far-right parties such as the Party for Freedom (PVV) in the Netherlands and Chega in Portugal have turned the affordable housing crisis into a central political and electoral issue. Their argument is simple: Housing should be available and affordable only for a country’s own citizens, as the main cause of the housing crisis is not only inflation but also migration.

“The European far-right is exploiting the housing issue precisely because the forces of the democratic arc abandoned it – either by dismissing it, naively, as a pure matter of market self-regulation, or because political inertia prevented them from imagining, developing and presenting to the public a long-term, alternative and sustainable housing plan for Europe,” concludes Seriatos.