Normal text sizeLarger text sizeVery large text size

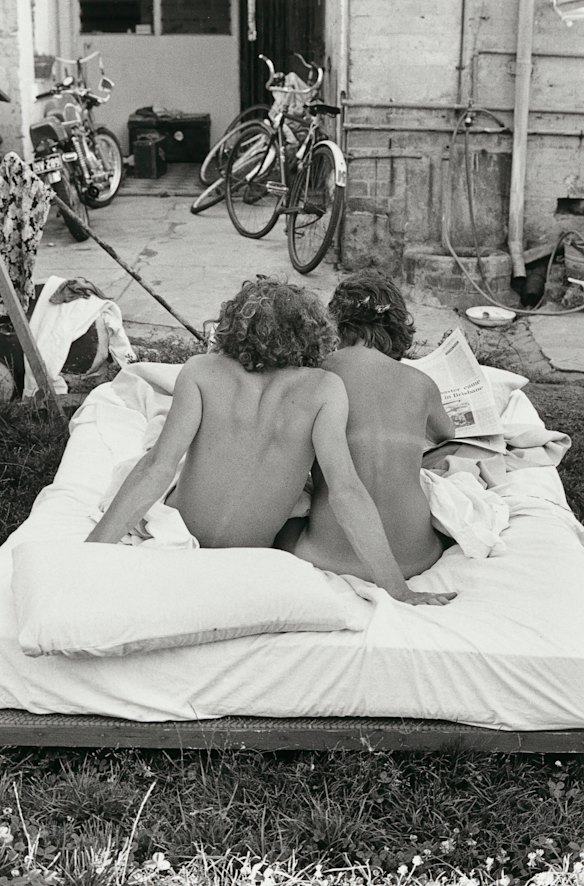

A naked couple sits on a mattress in the backyard of a terrace house, reading the newspaper, their backs to the camera. A motorbike and an assortment of pushbikes lean on the wall, a garden hose curls near an old drain, and dog’s water bowl suggests there’s an absent pet somewhere nearby.

It’s a gloriously evocative black-and-white photograph by Ponch Hawkes, typical of her work in the 1970s. Australia was undergoing a metamorphosis, emerging from decades of conservative government. Radical change was underway, with women’s rights, second-wave feminism and sexual liberation in full swing.

Hawkes documented those heady times and continues to do so, five decades on. Turning 80 next year, the acclaimed photographer is busier than ever, preparing for an exhibition of her paintings – a recent reacquaintance with the medium has turned into an obsession – and a survey show planned at the Museum of Australian Photography for winter 2028.

Ponch Hawkes’ No title (Summer night in the backyard at Falconer Street), circa 1975.Credit: Courtesy of the NGV

Her images appear in the newly published Circus Oz: From the Pram to the World Stage, and she features in the documentary The Language of Light about seven Australian photographers on SBS on Demand.

Some of her 1970s work is showcased at the NGV, in Women Photographers 1900-1975: A Legacy of Light. Her shots document that heady time and illustrate the changing social dynamics, capturing everyday moments like the above in communal houses, graffiti demanding childcare and social housing, protests about gay rights and women’s liberation and a whole lot more.

The images seem very uncurated, I say. “We were uncurated,” she says. “We were all so incredibly happy with ourselves. We all thought we were so fabulous.”

“It was punk, not in the sense of the Sex Pistols, but everybody was having a go at everything, trying out being a filmmaker or a writer or an artist or a photographer, in my case. With an overlay of social action and community giving and receiving.”

Places like the Pram Factory, La Mama and Circus Oz were in their infancy – the latter and its community remains a big part of her life; she was at a barbecue fundraiser for the rock’n’roll circus recently.

“I didn’t ever do the trapeze but we all tried to learn to do things. The thing is, I had strength but no grace whatsoever,” she says of its early days.

Ponch Hawkes has been documenting our lives for five decades.Credit: Chris Hopkins

One of the teachers was in traditional circus, which came with a particular type of training. “You’re up hanging off a rope and she’d happily let you wear the skin away, to see if you’re tough enough, which I wasn’t, really.”

Hawkes says it felt like the golden age: “Whitlam was in, the economy was in good shape, there was full employment, rent was really cheap, interest rates were low-ish and so there was money for the arts.”

”We were turning people away – everything we did was completely sold out. I went on tour in a band with five other women, to schools and all sorts of incredible venues, doing a show about women’s work, for which we had posters … in different languages, so if we performed at a factory, people would know what we were doing… bold things like that.”

She contributed to Digger magazine, the short-lived but impactful counter-culture mag that focused on politics, sex, drugs and rock’n’roll. Several of the images in the NGV show were first published in it, as was the essay that led to Helen Garner’s sacking as a teacher, for speaking with her high school students about sex.

We’re dining at Hawkes’ favourite local, Matsuya, a Japanese restaurant in Fairfield. It’s quiet and comfortable and the staff welcome her warmly. She orders the vegetable tempura with a side of horenso (cold spinach with sesame dressing, much more delicious than it sounds), while I opt for the deluxe bento box; we share the gyoza to start, plus Japanese tea.

Our photographer Chris Hopkins arrives and soon takes Hawkes outside to get a portrait shot, despite it being a wild and woolly day. “I’m ready for lunch, but am I ready for you?” she quips as they head outside.

Ponch Hawkes.Credit: Chris Hopkins

When she gets back, I wonder if she took a peek at the pics? No. (Later, when she sees his fabulous shot with her hair seeming to stand on end, she’s impressed and hopes we publish it.)

Often, Hawkes interviews people before shooting them. Everybody’s got a story, she says. “You get a sense of what that story might be. Also, if it’s a portrait and they need to present really well, sometimes people are really direct and go, ‘Oh no, I look terrible from that side’ – especially actors. But most people are completely unaware of how they present, so they’re really trusting you for a portrait.”

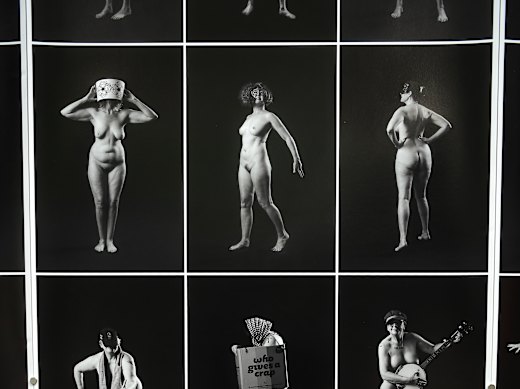

That degree of trust is a big part of what she does, perhaps best illustrated by her recent 500 Strong series, which features 500 women over the age of 50 photographed naked.

Some use props to cover their faces, many grin, smile or gaze happily into the camera; all show bodies of all shapes and sizes. It’s an extraordinary body of work and continues to tour around the country.

“I’ve done a lot of projects about good and worthy subjects, but this is the only one I’ve ever done that’s actually made real change,” she says. “Hardly a day goes by that I don’t run into someone, or someone writes me an email or a letter saying how differently they feel about things since they did the project or saw the project. It’s really moving.”

Born and raised in Abbotsford, Hawkes had three siblings; her dad was a laundryman at Abbotsford Convent and her mum sometimes worked as a cook in pubs.

Part of a panel of 500 Strong.Credit: Ponch Hawkes

Her dad played in the reserves for Collingwood and later trained local footy clubs; his family all played local footy, “they were big, strapping men”.

Now a self-confessed diehard Collingwood fan, she didn’t re-engage with footy until later in life. “I can’t remember what it was but I became fully engaged,” she laughs, even writing a spirited defence of Mason Cox when he was attacked in an online supporters group.

Her miniature poodle wears a Pies jumper in a pic on her phone and her membership for the next season has just arrived in the mail. Being a Collingwood supporter means you commune with fellow supporters, “no matter where they come from – that’s what tribes are about”.

We’re both thrilled to see women playing Australian Rules, finally, even though the physicality of the game can mean it’s sometimes hard to watch.

“Because we’re so unused to seeing girls tackle other girls or go in head-first or slam into people or do all the things we’re used to in AFL. That’s one of the reasons we love it so much, it’s such a brutal bloody sport.“

Footy chat brings us to Helen Garner’s wonderful book The Season, about her grandson and his local team. “That book made me feel glad to be alive and Helen’s books aren’t always like that… [it] was so full of joy. I just completely love her, she’s such a brilliant writer.”

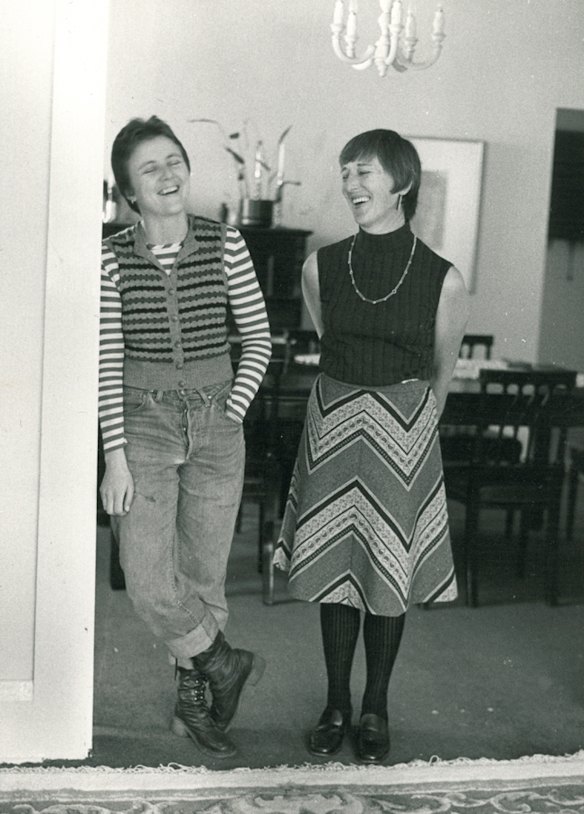

Helen and Gwen 1976, from the series Our mums and us by Ponch Hawkes.Credit: Ponch Hawkes/Museum of Australian Photography

I find out over lunch that it’s actually a young Garner in that photo described at the beginning of this piece.

She also features in Hawke’s series Our Mums and Us, which features mothers and their daughters photographed at their homes. It’s a wonderful snapshot of time, borne out of the realisation “that your mother was not just your mother, she was a person in her own right”. In 1976, it became her first exhibition.

There are many similarities between their work: social realism and making art by documenting our lives, an incredible eye for detail, and a commitment to truth-telling.

Trailblazing publishers McPhee Gribble commissioned Hawkes to take photographs for a book called Generations, written by anthropologist Diane Bell, featuring grandmothers, mothers, and their daughters. She shot the covers of many of their books over the years; the Generations pics later formed her solo show at the NGV.

Social justice is a through line of her work, an integral part of her worldview. That continues to this day, with a new series underway about sexual violence and older women, a joint project with academics at Melbourne University.

It will involve interviews and pictures, although at this stage it remains to be seen what the images will be. “If you’re homeless or you’ve been assaulted, who wants a picture of that? You don’t even want to be identified.”

Hawkes at Matsuya Japanese in Fairfield.Credit: Chris Hopkins

“People think that sexual violence only happens to younger women but it doesn’t – and it’s not only in places like nursing homes either.”

For two years, Hawkes regularly attended the weekend Melbourne protest marches over Israel’s war in Gaza. She has made art about Palestine in the past and intends to do so in the future. “The kids are going to say to us, ‘why didn’t you do something about it?’”

While continuing her photographic practice, Hawkes has started painting classes again, for the first time since art school after leaving high school. She’s completely enamoured by it, learning every day.

Ponch Hawkes’ Isolation husband (2020) from the series The Plague.Credit: Ponch Hawkes

“It’s constantly figuring stuff out … It’s so testing, it’s really difficult,” she says. “I have an incredible amount of ideas.

“Very frequently, with work, you don’t know what it is until someone tells you, or writes an article about it, or comes in and says something and you think ‘that’s what it’s about’, or you do know what it’s about but you’re keeping it to yourself, or you think it’s mad,” she says.

Tempura vegetables at Matsuya.Credit: Chris Hopkins

Some of what she’s making harks back to work she created as a young woman. “When I was at art school, I did a whole lot of work about animals and our relationship to animals, and it’s similar work.”

Hawkes and her partner, painter and sculptor Ian Bracegirdle, met later in life, not long after her father died. She spied him outside the Fitzroy Town Hall heading into the Fringe Furniture show and stopped; it is true love, she says.

During lockdown, he wrote a recently released album called The Weather is Broken, with band BlueBoat Theory. In September, they will stage a joint exhibition at 45 Downstairs called Sex and Death and Country.

Ponch Hawkes’ No title (Two women embracing, “Glad to be gay”) 1973, NGV. Credit: Ponch Hawkes

People tell Hawkes her paintings are like her photography. “I don’t know that I quite agree with that, but there must be an element of it,” she says.

The joy inspired by making art with this new-found old medium is exponential and she is thrilled to have rediscovered it.

“There’s also a confidence element. I feel like I’m completely out of my depth but if I persist and I keep going and I ask people and I read up and practice, I’ll be able to do what I want to do.”

Receipt for lunch at Matsuya Japanese with Ponch Hawkes.

Women Photographers 1900-1975: A Legacy of Light is at NGV International until May 3; Sex and Death and Country is at 45 Downstairs from September 11. Circus Oz: From the Pram to the world stage is out now via Melbourne Books.