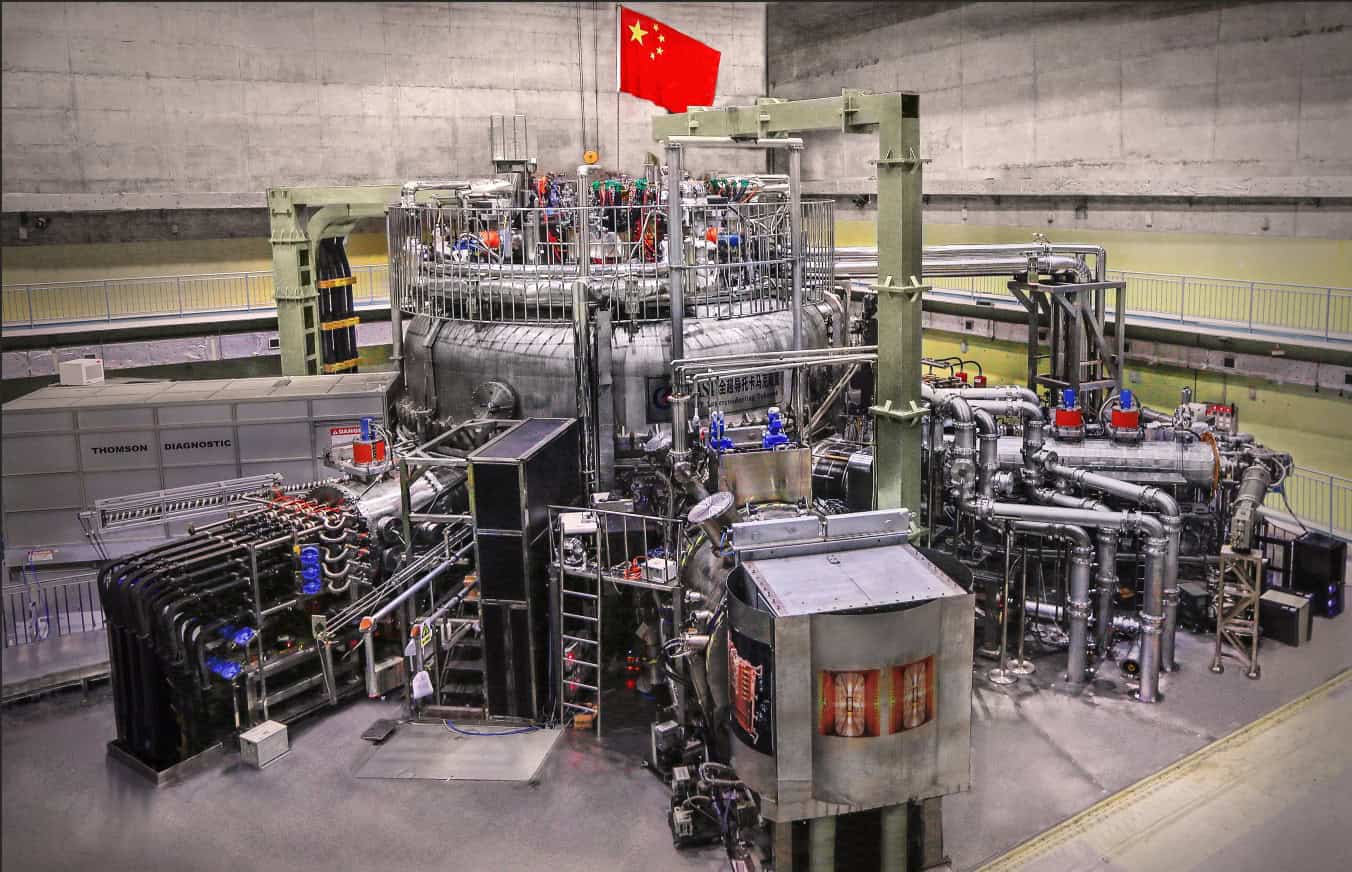

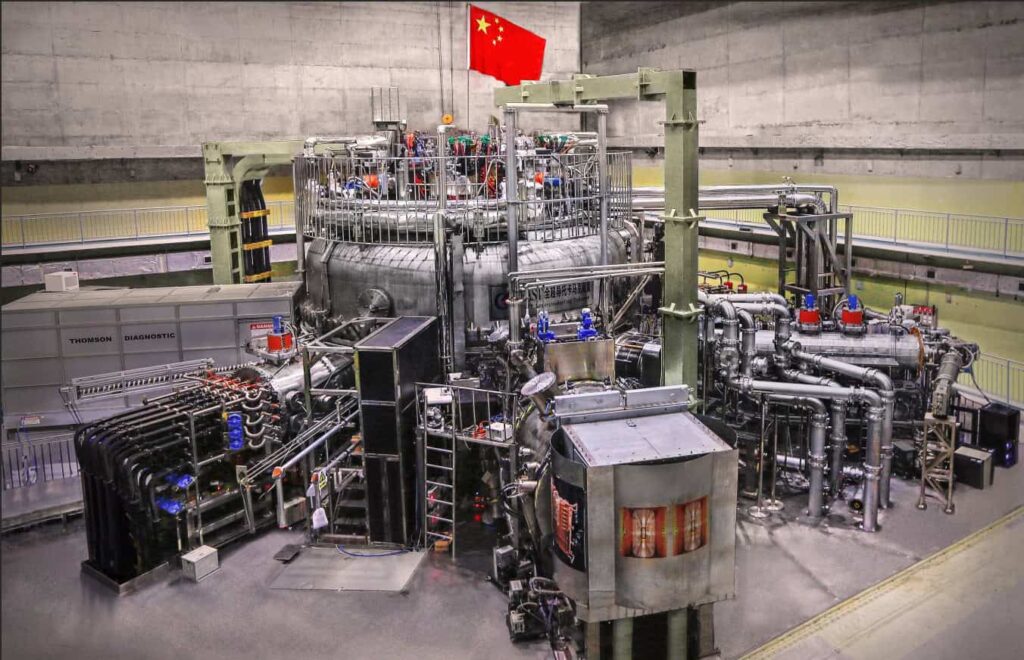

As the world’s first superconducting tokamak, EAST(Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak)has three distinctive features: non-circular cross-section, fully superconducting magnets and fully actively water-cooled plasma-facing components (PFCs). Credit: Chinese Academy of Sciences.

As the world’s first superconducting tokamak, EAST(Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak)has three distinctive features: non-circular cross-section, fully superconducting magnets and fully actively water-cooled plasma-facing components (PFCs). Credit: Chinese Academy of Sciences.

Fusion physicists have always been haunted by a ghost in the machine known as the Greenwald limit. It’s a frustratingly empirical ceiling: try to cram too much plasma into your magnetic donut (tokamak), and the whole thing goes haywire, effectively killing the reaction.

But on January 1, researchers working on China’s Experimental Advanced Superconducting Tokamak (EAST) — often dubbed the “artificial sun” — announced something remarkable. They hadn’t just broken this rule; they may have rewritten the playbook for how we build stars on Earth.

In a new paper published in Science Advances, the team revealed they achieved a steady plasma operation at densities ranging from 1.3 to 1.65 times the Greenwald limit. More importantly, they did it by accessing a theorized state of matter called the “density-free regime,” where the plasma stabilizes itself rather than tearing apart.

“The findings suggest a practical and scalable pathway for extending density limits in tokamaks and next-generation burning plasma fusion devices,” says Zhu Ping, a professor at Huazhong University of Science and Technology and co-lead of the study.

If validated and scaled, this breakthrough suggests that future fusion reactors like the massive ITER project in France might be able to run at higher capacities — or perhaps even be built smaller and more cheaply than we dared to hope.

The Density Dilemma

To understand why this matters, you have to look at the math of making a fusion reactor. Fusion works by smashing light atoms (like deuterium and tritium) together to form heavier ones, releasing massive amounts of energy. To get a net energy gain inside an “artificial sun”, you need three things: intense heat (around 150 million Kelvin), enough containment time, and high particle density.

The density part is crucial because thermonuclear power scales with the square of the fuel density. Doubling the density doesn’t just double your power output; it quadruples it.

But for years, tokamaks have hit a wall. When operators try to push the electron density too high, the plasma typically becomes unstable and disrupts, crashing into the reactor walls. This ceiling, the Greenwald limit, has been treated as a “hard operational ceiling for decades,” according to Chris Eaglen, vice-chair of the IChemE’s nuclear technology special interest group, in an interview with Live Science. Engineers have designed entire machines and safety protocols assuming this limit was a fundamental law of physics.

×

Thank you! One more thing…

Please check your inbox and confirm your subscription.

The EAST team, however, treated it as a problem of housekeeping. They utilized a theory called plasma-wall self-organization (PWSO), proposed in 2017 by French researchers, which suggested that the limit wasn’t about the plasma itself, but about how the plasma interacts with the environment of the reactor walls.

Cleaning the Walls with Microwaves

The experiment at EAST wasn’t just about cranking up the dial. It was a delicate ballet of heating and fueling performed during the reactor’s start-up phase. The researchers combined ohmic heating (running a current through the plasma) with Electron Cyclotron Resonance Heating (ECRH) — essentially blasting the electrons with precisely tuned microwaves.

By carefully controlling the prefilled gas pressure and applying up to 600 kW of ECRH power, they managed to keep the reactor walls cleaner and cooler. In typical runs, impurities sputtered off the tungsten divertor plates (the exhaust system of the reactor) drifting into the plasma, cooling it down and causing instability. But the EAST team found that their method reduced this physical sputtering, lowering the “target temperature” at the divertor.

This created a feedback loop (a “virtuous process”) where cleaner plasma allowed for lower edge temperatures, which in turn produced fewer impurities. The result was a plasma that didn’t just survive high density; it thrived in it. They entered the “density-free basin,” a stable mode of operation where the Greenwald limit effectively moves up to an extremely high value, untethering the reactor from its old constraints.

The researchers managed to maintain this state with line-averaged electron densities of roughly 5.6 × 10¹⁹ m⁻³, significantly higher than the machine’s typical operational range.

A New Era for ITER?

This isn’t the first time a reactor has nudged past the Greenwald limit. The DIII-D tokamak in San Diego broke the limit in 2022, and the Madison Symmetric Torus in Wisconsin recently hit densities 10 times the limit. However, the EAST result is distinct because it specifically validates the PWSO theory in a standard tokamak configuration with metal walls (tungsten), similar to what will be used in commercial reactors.

The implications for ITER, the multinational fusion megaproject, are tantalizing. ITER is scheduled to begin full-scale fusion reactions in 2039. If ITER can utilize this “density-free regime,” it could potentially reach its ignition goals more easily.

“It means that reactors may not need to be as large or as conservative in density assumptions,” Eaglen explains.

Interestingly, the EAST results also bridge a gap between tokamaks (donuts) and stellarators (the twisted-ribbon reactors like Germany’s Wendelstein 7-X). The EAST data shows that tokamaks can operate in a regime previously associated with stellarators, where high density is easier to achieve because the confinement is available from the outset.

Not a Shortcut, But a Path

Despite the excitement, experts warn that this isn’t a warp speed jump to unlimited energy. “The limit is not a fundamental law, but a consequence of how plasmas are formed and interact with walls,” says Eaglen, noting that this breakthrough “improves confidence in future reactor designs rather than accelerating timelines”.

Fusion is still an experimental science. The record for sustained plasma is just 22 minutes (held by France’s WEST reactor), and while we have achieved net energy gain in laser-based inertial confinement, magnetic fusion is still chasing that breakeven point.

However, the EAST experiment proves that the “hard limits” of physics are often just engineering challenges in disguise. By understanding the subtle dance between the plasma and the wall, humanity has taken one more step toward bottling the stars.

As Associate Professor Yan Ning of the Hefei Institutes of Physical Science noted, the team now plans to apply this method to high-confinement operations, hoping to push the “artificial sun” even closer to the real thing.