Officials warn that the only part of Western Australia’s north untouched by new fishing restrictions is likely see a flood of anglers fleeing north, and locals are questioning if the region can cope.

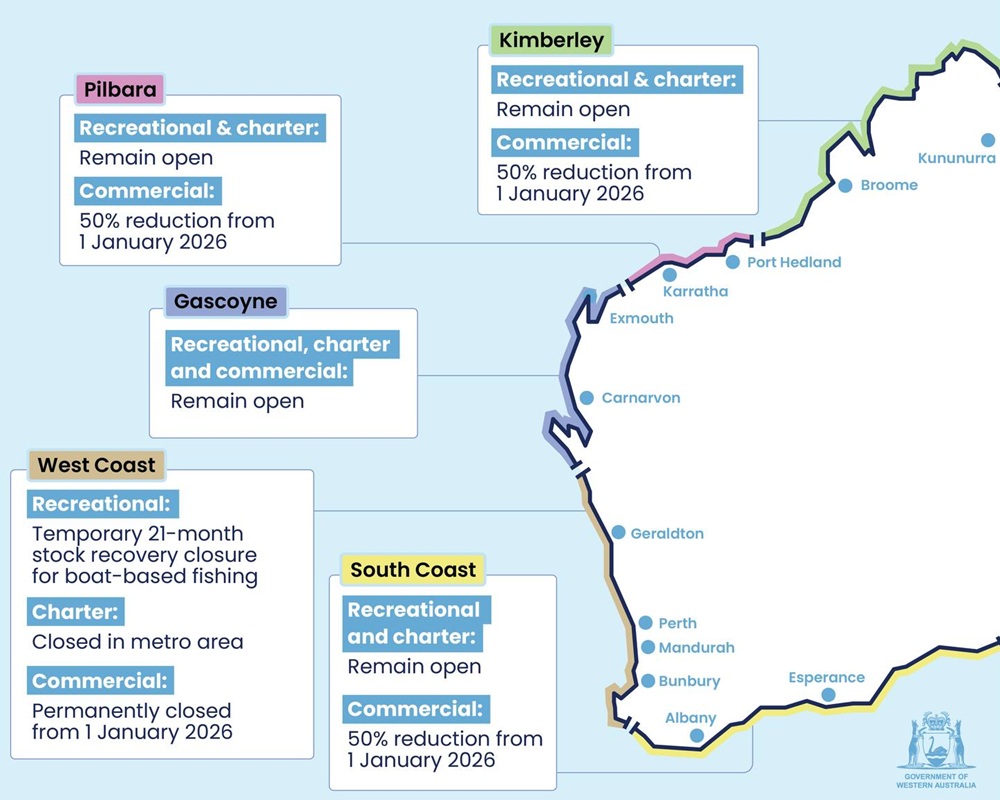

Beginning in January, recreational fishing for species like dhufish, red emperor and pink snapper was banned for 21 months from Kalbarri to Augusta.

Commercial demersal fishing was also closed on the West Coast bioregion, and catch numbers were halved in every region, except the Gascoyne.

Sweeping restrictions were introduced around the state in January. (Supplied: DPIRD )

Calls for more education

Yinggarda custodian and tour guide operator Rennee Turner is concerned the region is not ready for an influx of fishers.

It follows similar concerns in Windy Harbour, on the state’s south coast, which also sits outside the zone impacted by the ban.

Rennee Turner fears for the health of Country, but is looking forward to more opportunities for local businesses. (Supplied: Rennee Turner)

“My biggest concern is the environmental impact from human beings not being educated enough and not having an understanding of how fragile our coastline actually is,” Ms Turner said.

“Every man and their dog is going to want a fish [here]. Do we have the capacity to have these people?”

She said there was not enough time afforded to prepare for the expected boom, exacerbated during the busy tourist season in the winter months.

Some fear that new rules sweeping the rest of WA could push fishers into the Gascoyne. (ABC Pilbara: Kelsey Reid)

As a traditional custodian, Ms Turner called for more signage around significant cultural and environmental sites, to be installed in collaboration with First Nations people.

The Gascoyne is famously home to two UNESCO World Heritage areas, the Ningaloo Reef and Shark Bay, the latter of which shelters the largest seagrass bank in the world.

“It’s not just the seagrass we need to be concerned about; it is the dune systems themselves. You’re going to have caravans and four-wheel drives [in the dunes],” she said.

“As a tour operator, of course, I want to encourage visitors, but I think it’s way too early to be allowing that much impact to happen in our space without educating people.”

A fisherman pulls his catch off the line in Exmouth. (ABC Pilbara: Kelsey Reid)

Keeping the Gascoyne sustainable

Demersal stocks, and particularly pink snapper, have recovered steadily in the Gascoyne since coming close to collapse almost a decade ago.

In 2018, the Department of Fisheries reduced the Gascoyne’s commercial sector pink snapper quota from 277 tonnes to 51.42 tonnes.

It also closed fishing during the peak spawning period in certain areas and reduced commercial size limits.

Sunset at Monkey Mia, a popular tourist spot in Shark Bay. (ABC Pilbara: Alistair Bates)

Department of Fisheries executive director Nathan Harrison said the Gascoyne fishing zone was now a “success story”.

“We’ll be using that to model management for around the state,” he said.

Mr Harrison insisted the process required patience.

“That quota management system that’s in place for the Gascoyne, we are now going to put into the Pilbara, the Kimberley, and also the South Coast to really manage the commercial catch to quite explicit catch levels,” he said.

“It will be a long-term process of at least 10 to 15 years, possibly 20, which requires careful management along the way.”

The Gascoyne’s commercial pink snapper quota was slashed in 2018, setting the stage for the species’ recovery. (Supplied: DPIRD)

He said he was “mindful” the ban might push people into less restricted waters, but a review of bag and size limits was already underway.

“In the Gascoyne it’s more of a mix with commercial and recreational, and you need to make sure that you’re managing both sectors,” Mr Harrison said.

“You can’t just manage one sector in isolation and just hope that the fishery remains sustainable.”

Concerns around communication

Scott Clarke says he has “a foot in each camp”. (ABC Pilbara: Rachel Hagan)

Carnarvon tackle shop owner Scott Clarke said he knew of several fishing clubs that had already booked trips to the region.

He said he had “a foot in each camp” because he could see the benefits fishing tourism could bring to local communities.

“That will create business for everyone — from the pub owner, the ice maker, myself, and accommodation,” he said.

However, Mr Clarke said he and many of his customers wanted more communication around the scientific research which led to the ban.

“As long as the science is proven and not just an excuse to kick us out,” he said.