At the end of every day the Barrett family puts a colourful sticker on the lounge room wall.

It’s a symbol they have survived another day without their precious daughter and sister Abbey who died of brain cancer 18 months ago.

She was 11.

Justine says that since losing Abbey the family “talk a lot about her” as a means of coping. (ABC News: Maren Preuss)

Mother Justine, father Rick and sisters Willow and Tasmin try to honour Abbey in little ways every day.

Her teddy is at the dinner table where she used to sit and a vegetable patch has been replaced with a flower garden.

“None of it feels like enough but we’re very open, we talk a lot about her,” Justine said.

Abbey Barrett in hospital during treatment. (Supplied: Barrett family)

If you or anyone you know needs grief support:Griefline: Phone support for all Australians Monday to Friday and 24/7 online forums. Call 1300 845 745 from 8:00am to 8:00pm AEDTLifeline: 24-hour support for all Australians on 13 11 14

Abbey was the youngest of the girls, all close in age, and a “cool human” according to Justine.

“She was joy on two legs. She was like a puppy, she just brought that energy and joy,” she said.

When Abbey was 10 her parents noticed she was tired and had developed hand tremors.

She had a blood test and everything was normal.

But when she started having trouble with her vision, an MRI revealed she had a brain tumour the size of a fist wrapped around her brain stem.

The family felt a shock “almost like an earthquake”.

Justine says they decided “when you die you go to a park that’s full of loaded fruit trees and puppies”. (ABC News: Maren Preuss)

“We have no family history of cancer. Yet cancer still found us in the worst way,” Justine said.

“We went from having Lego and books on the kitchen table to medications and cancer brochures. It was incredibly surreal,” she said.

Abbey had two brain surgeries, chemotherapy and radiation.

While the Barretts were supported by medical professionals, navigating her care was difficult, with them needing to make calls on when to take her to hospital or when to manage her symptoms at home.

Abbey’s mother Justine said her daughter knew she was dying. (Supplied: Barrett family)

“These decisions were one of the hardest parts because the consequences of making the wrong decision were literally life and death.”‘She died at home, in our bed, in my arms’

Justine said Abbey knew she was dying.

“I had to have conversations with her about what that meant,” Justine recalled.

“We decided that when you die you go to a park that’s full of loaded fruit trees and puppies.”

Justine says her other daughters struggle with the weight of the grief of losing Abbey. (ABC News: Maren Preuss)

Abbey died a year after her diagnosis.

“She died at home, in our bed, in my arms. We tried to make her death as gentle and easy as possible,” Justine said.

But Abbey’s death was far from easy.

“Why don’t we have voluntary assisted dying for children? The last ten hours of Abbey’s life were agony to witness,” Justine said.

At the same time, Abbey’s parents needed to consider how their other two girls were coping.

They wanted to normalise the death and grieving as much as they could.

“After she died we drew pictures and wrote messages on her stomach and arms as a way of sending her body off with love,” Justine recalled.

She said her daughters struggle with the weight of the grief of losing their sister Abbey.

“They’ve had some pretty big challenges since,” Justine said.

“I am really proud of them, it’s been a really big journey.”

Abbey’s sisters and the many photos of Abbey in their home. (ABC News: Maren Preuss)

Older sister Willow said she felt helpless watching Abbey suffer through brain cancer.

“I don’t think I can put into words how hard it was,” she said.

“My mental health journey has been very bumpy since so I am having to do part-time at school.”

Justine has chosen to share her family’s story, hoping it will send message to the Australian government.

“Put some funding towards brain cancer, because we’re failing our children,” she said.

“Our job as adults, at the very least, is to raise our children to become adults themselves and we’re failing that.”

Abbey Barrett died a year after her diagnosis. (Supplied: Barrett family)

The ‘horrible’ statistics

Brain cancer, often described as “rare”, accounts for about 2 per cent of all cancers.

To put that figure into perspective, more Australians die of brain cancer than the number of people killed in road accidents every year.

Remembering Charlie and others gone far too soon because of brain cancer

In 2023, Australia saw 1,579 people die from brain cancer, compared with 1,254 road crash deaths that same year.

It’s the disease that kills more Australian children under 14 than any other.

Brain cancer’s five-year survival rates have only improved marginally in the last three decades, from 19 per cent (1990-1994) to 23 per cent (2015-2019).

“That flat, virtually flat curve and low survivability is a horrible statistic,” said Craig Cardinal from Brain Tumour Alliance Australia.

“It’s hard not to be heartbroken by that.”

Brain cancer victims are remembered at Parliament House, Canberra, as part of 2025 Head to the Hill event. (ABC News: Andy Cunningham)

In recent years the shoes of Australians who have lost their lives to the disease have been placed on the lawns outside Parliament House in Canberra.

It’s a call for action and funding.

Renowned doctor’s cancer battle ‘getting closer’ to the end

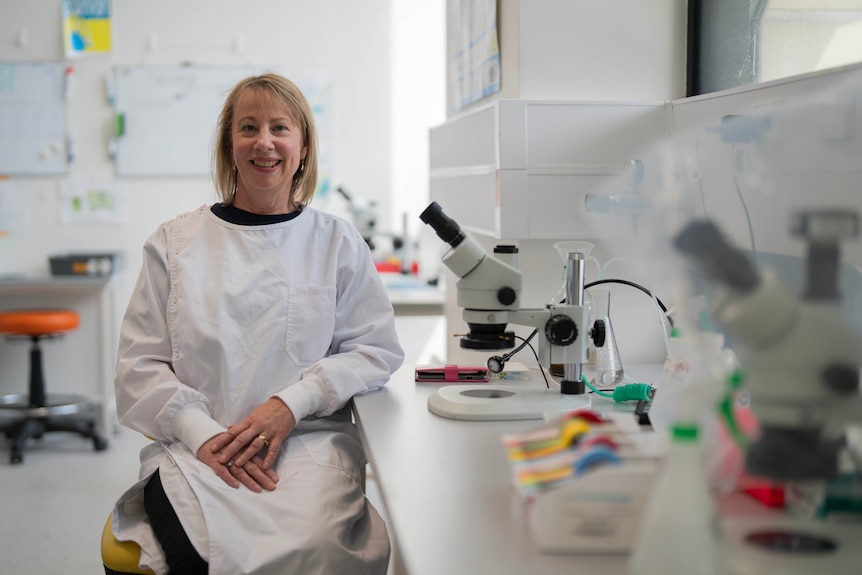

Dr Rosemary Harrup is a medical oncologist and researcher at the Menzies Institute for Medical Research in Tasmania.

She said while there is a range of different brain cancers, the most aggressive is glioblastoma.

“About a quarter of these people are alive at two years [after diagnosis]. These are devastating figures,” Dr Harrup said.

New techniques to cross the blood-brain barrier offering hope

While brain cancer is complex and difficult to treat, surgical techniques to remove tumours have improved in recent years.

“Unfortunately there’s always going to be residual cells from which the cancer will regrow,” Dr Harrup said.

Professor Rosemary Harrup is one of those working to solve the blood-brain barrier puzzle. (ABC News: Maren Preuss)

Treatments span radiotherapy, chemotherapy and immunotherapy — but there are challenges.

The brain is protected by an intricate network of blood vessels, which work to protect it from foreign materials.

“That’s called the blood-brain barrier, and so most treatments need to be able to cross that to be effective,” Dr Harrup said.

She said an international study using ultrasound to open the blood-brain barrier for short periods, combined with chemotherapy, is proving promising.

“It’s almost like science fiction and can allow the drug just in that short window of opportunity to cross into the brain.”

Researchers at the Menzies Institute are using flies to help develop brain cancer treatments for humans. (ABC News: Maren Preuss)

Working out which part of the puzzle is broken

Associate Professor Phillippa Taberlay and her team at the Menzies Institute are working on finding solutions at the DNA level, looking at a type of childhood cancer called medulloblastoma.

“It’s a type of cancer which has a very high rate of epigenetic dysregulation, which means the way genes are expressed have been altered,” Dr Taberlay said.

“We are looking at how DNA inside of the cell is folded or modified with little chemical tags.”

Dr Phillippa Taberlay says discoveries about brain cancer are applied to other cancers. (ABC News: Maren Preuss)

She said understanding which chemical tags aren’t behaving as they should will help determine where the fault in the body is.

“If we can discover which proteins or parts of the puzzle are broken we will be able to use really sophisticated genetic tools or new pharmacology to treat brain cancers,” she said.

Dr Taberlay believes any discoveries about brain cancer could be applied to other cancers.

Abbey is remembered by her family as being “like a puppy … she just brought that energy and joy”. (ABC News: Maren Preuss)

Brain cancer missing out on funding

Clinical trials of new treatments can offer hope to cancer patients, but Dr Harrup said funding for them is limited.

“It is unfortunate that if you live in a major capital city and you have brain cancer you are much more likely to be able to enrol in a clinical trial than if you live in country Victoria or Tasmania,” she said.

Brain cancer’s survival rates have changed little over the past 30 years and is the cancer that kills the most children in Australia. (ABC News: Andy Cunningham)

Brain Tumour Alliance Australia has been mapping the burden and economic cost of brain cancer in Australia, which in 2025 was $850 million.

If trends continue the mapping estimates the cost at $3.2 billion by 2050.

It’s hoped the mapping will unite the brain cancer community and fundraising efforts, and make research and funding a government priority.

Justine leafs through a scrapbook for Abbey, her tattoo tribute visible on her wrist. (ABC News: Maren Preuss)

The alliance is asking the federal government for $200 million over 10 years for brain cancer research and trials, and up to $10 million to improve clinical care for patients, including funding for specialised nurses.

“The burdens and impacts are disproportionately high, the complexity of the disease is disproportionately high, but our funding and policy approach to address that complexity is mismatched,” Mr Cardinal said.

Craig Cardinal is one of those heading the campaign to lobby for more money to fight the disease. (ABC News: Mark Moore)

The Alliance said direct research funding for brain cancer has consistently lagged behind other cancers.

It states that from 2003 to 2020 brain cancer received $111.6 million in total project funding — well below breast cancer ($431.6 million) and leukaemia ($234.7 million).

In 2017 the Australian Brain Cancer Mission invested $126 million over 10 years for brain cancer research, $50 million came from government, while $76 million was from philanthropic organisations.

“I’m certainly committed to doing more … as that mission comes to an end. We’ve already started discussions with the Brain Cancer Alliance about what that looks like,” said federal Health Minister Mark Butler.

Mark Butler says the government is “working as hard as we can” to get cancer drugs on the PBS “as quickly as possible”. (ABC News: Rebecca Trigger)

“In the meantime whenever there are new treatments, particularly for children with brain cancer, we’re working as hard as we can to get those medicines available to families on the PBS as quickly as possible.

“This is a stubborn area of cancer where I think every country, including ours, wants to see improvement.”

Dr Harrup said “talking about a cure is important because that’s what we strive for and that’s what our mission is.”

“For those patients we can’t cure right here and now, improving quality of life and quantity of life are both very, very meaningful goals,” she said.