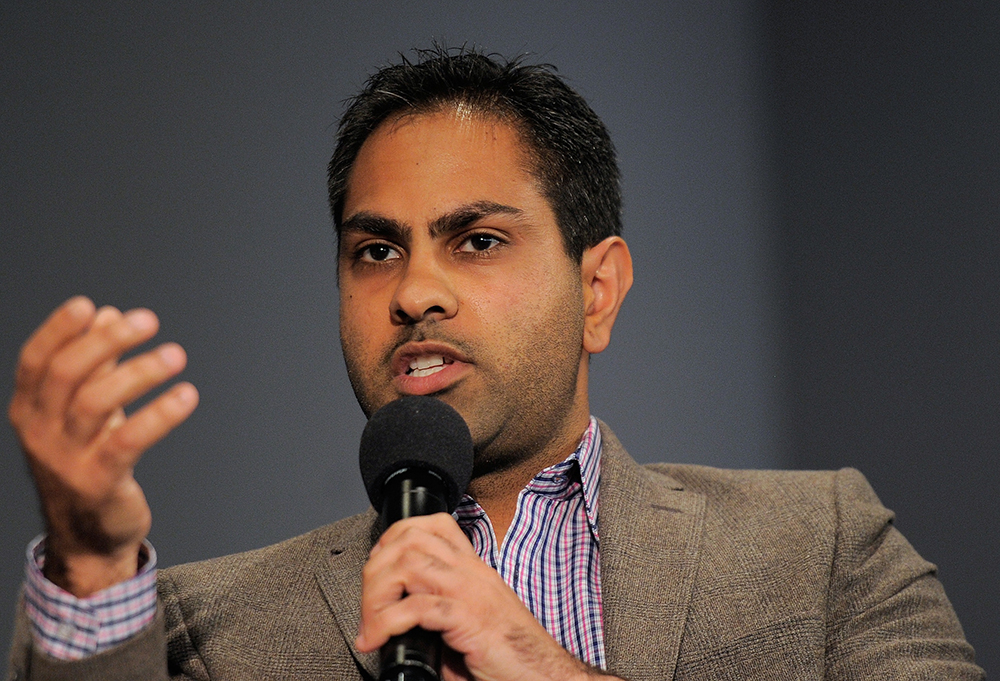

Ramit Sethi wants to make you rich. He is not a household name in Britain, but the Stanford psychology graduate is one of the biggest personal finance influencers in the US. He hosts a successful podcast, Money for Couples, has written bestselling books and even has a Netflix show, How to Get Rich. All his projects share the same message: by changing your mindset and taking a few practical steps, you can power yourself toward prosperity.

To British ears, his style might seem brash. It is financial advice with a substantial side of life coaching. But beyond the difference in tone, Sethi spreads a simple message rarely heard in finance columns or consumer advice TV slots in this country: that the best thing you can do for your money is to rapidly increase your income.

On his website, tips on controlling your outgoings are nestled alongside advice on securing a pay rise. In his TV show, he encourages families not only to cut unnecessary subscriptions and tame their spending, but also to switch careers to maximise their income. It is part of a broader difference between American and British financial advice. While our experts are savings maximisers, their American counterparts focus more on increasing your ability to pull money in.

Across social media and podcasts, Americans are encouraged to boost their salaries, launch their side hustles and sweat their assets. British channels, by contrast, are much more reserved, with an emphasis on changes to the other side of the ledger. Advice focuses on controlling bills, cashback cards and loyalty points. It is small fry and conservative, the opposite of Sethi’s mantra of ‘$30,000 questions, not $3 ones’.

The difference embodies a broader cultural difference. Americans are encouraged to take greater risks and pursue greater dreams. British advice is parsimonious and loss-averse. Even when it comes to savings, we are shepherded towards the safest options. While Americans are urged to play the market, we are offered better current accounts. This both exemplifies and encourages an overly cautious approach to money, which leaves the UK at a disadvantage.

Beyond the puff of podcasts, Britons are missing out on real financial advantages. Outside of pensions, less than a quarter of people in the UK invest any money in the stock market. More than two-thirds of Isas are cash-only, and less than 10 per cent of our personal wealth is invested in equities. This lags behind the US, where two-thirds of people have money in the market, and also the rest of the G7, where on average 15 per cent of personal wealth is held in stocks. The government is trying to nudge us in the right direction by limiting the cash component of Isas to £12,000 from next year.

Fear of investing appears to be a consequence of national risk aversion. Two-thirds of Britons say that putting money into stocks and shares is ‘too risky’, opting instead for products where their capital remains safe. They are missing out. In recent years, markets (especially in the US) have surged, while savings rates have languished and been eroded by inflation. If you’d started 2020 by putting £1,000 in an S&P tracker, your money would have more than doubled by the start of this year. Even the top savings accounts would have earned only a couple of hundred pounds in that time.

Tied to this is our national obsession with property wealth. In Britain, property investment is perhaps the only socially acceptable form of capital accumulation. A scroll through Instagram will show dozens of accounts sharing tips, from the practical to the dubious, about flipping homes, maximising rental yields and building property empires from almost no capital. It’s presented as the perfect play – high reward with little risk. This advice ignores the reality that policy choices made housing a one-way bet for a fortunate older generation, but that future growth is far from guaranteed.

Americans are encouraged to play the market, while we’re shepherded towards the safest options

The contrast with the US is telling. There, households are encouraged to spread risk across markets and time. Here, advice culture and social norms combine to channel risk into a single dominant asset class, while treating broader market participation as optional or intimidating. For those with a greater risk appetite, the gap leads them to seek worse advice and to fall under the influence of those who peddle get-rich-quick alternatives, such as day trading, cryptocurrency and outright gambling. The forums and YouTube channels that do push more sensible portfolio approaches tend to be niche and are favoured by the already well-off and financially savvy.

The result is a British public with remarkably under-optimised finances. We jealously guard our energy tariffs, shop around for our broadband and then push the proceeds into underperforming accounts. A lifetime of caution leaves us personally much poorer than we should be and creates a crisis for the state when people enter retirement. Rather than learning to ride the bumps of the market, we avoid risk without noticing the money we leave on the table.

The bravado of Sethi and his compatriots is unlikely to win over many British viewers. Reticence about money is one of the greatest cultural divisions between Americans and us. The life-coach-style dream of achieving your ‘rich life’ instinctively feels like vulgar nonsense. These influencers, however, can teach us things our homegrown advisers miss.

Savvy spending and shrewd saving are, quite obviously, only one side of the ledger and there is only so much thriftiness can deliver. A better job and a higher income deliver life improvements on a scale that 1 per cent cashback will never muster. Likewise, long-term investments in the market, with a healthy spread of risk, will outperform even the canniest jockeying between savings accounts.

It’s often said that culture eats strategy. Britain’s approach to money is obviously shaped by its culture – both our deep-seated reserve about financial matters and the ideas that bounce around the public sphere. Hearing more about shopping around has made us more promiscuous with our utilities and allowed us to reap the benefits of consumer pressure.

However, too many of these are Sethi’s ‘$3 questions’. The bigger value ones are about growth, ownership and ambition, and those are still treated as faintly un-British. Until that changes, we will remain very good at saving pennies and oddly reluctant to pursue pounds.