January 24, 2026 — 5:30am

Save

You have reached your maximum number of saved items.

Remove items from your saved list to add more.

Save this article for later

Add articles to your saved list and come back to them anytime.

Got it

AAA

In a popular YouTube video from a couple of years ago, a well-known Sydney graffiti writer who goes by “TAVEN” films himself wandering around the Art Gallery of NSW.

As he appraises some of the work (“I love coming here,” he says), he asks an attendant whether there is a graffiti section he could look at.

“I’m not sure but if you want to check with the information desk …” is the response.

After receiving several more similar answers to his polite inquiries, he leaves the 150-year-old museum and wanders out into the Domain to a nearby wall long a favourite among local graffiti writers. The camera pans past 60 or more “burners” – top quality, vivid pieces created by the best writers – along the 200-metre wall.

Fiona Lowry wanted to know what happened when graffiti was brought in from the street. Wolter Peeters

Fiona Lowry wanted to know what happened when graffiti was brought in from the street. Wolter Peeters

“It’s not inside – they actually put it outside,” says TAVEN with deadpan irony.

The unmistakable message here: street art has no legitimate place in a “proper” gallery. It should be excluded from official, sanctified spaces and relegated to the street.

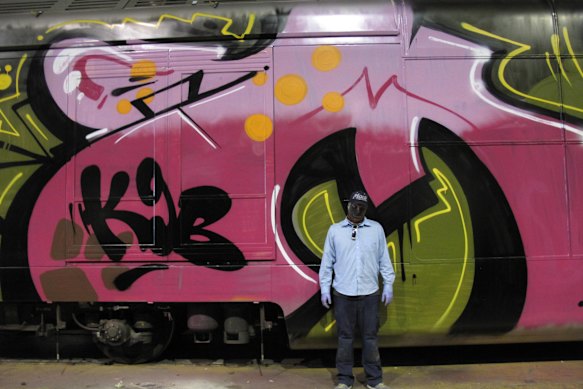

But what happens if you bring graffiti into a gallery space? This question – among many – has captured Fiona Lowry, who, along with co-curator Katrina Cashman, has put together a new exhibition at Darlinghurst’s National Art School. Searchers: Graffiti + Contemporary Art is described as “an exhibition about the politics and poetics of spray”.

Work by graffiti writer MACH.

Work by graffiti writer MACH.

Works included range from household names including Sidney Nolan, Howard Arkley and Ben Quilty to graffiti writers such as TAVEN, SPICE and MACH, all legends in street art circles but whose names most of us might have glimpsed only on an inner-city wall or perhaps from the window of a moving train. Some of the works have been created directly on the gallery walls.

For Lowry, the exhibition is not about conferring “legitimacy” on street art by hanging it in a conventional gallery.

“[It’s] not a show about extracting graffiti from the street and translating it into gallery terms. If anything, the exhibition holds a tension between different value systems,” she says.

A detail from an untitled 1987 Sidney Nolan spray can work from his Remembrances of My Youth series. Photo by Rob Little

A detail from an untitled 1987 Sidney Nolan spray can work from his Remembrances of My Youth series. Photo by Rob Little

“Graffiti doesn’t so much ‘lose value’ in the gallery as shift value. On the street, it holds power through risk, speed, territory and peer recognition. In the gallery, different things become visible: form, discipline, lineage and the deep relationship to authorship and mark-making. Part of what the exhibition tries to do is hold those two value systems in tension rather than pretend one replaces the other.”

The seed for the show was sown when Lowry’s own son, then aged about 11, became swept up in the graffiti world.

“What I discovered by watching him was that he had this really intense experience with it where he was constantly refining his word and the form of it and connecting with other writers online and watching films,” says Lowry.

She also recognised that within graffiti culture, there was an organised pedagogy in which experienced writers mentored up-and-comers.

“The older writers will often do sketches for the younger writers,” says Lowry. “It’s almost a way of continuing their own style into that next generation. It’s a very unofficial kind of art school.”

Searchers occupies two levels of the National Art School Gallery, and each space is intended to present a different experience for the viewer.

Lowry describes the lower level, which is darker and more intimate, as a “charged space”.

“I wanted it to unfold in sequences, almost like a film,” she says. “Upstairs shifts into a different register, like an after-image. It becomes lighter, more optical and painterly – spray as drift, spray as breath – and it changes how the downstairs lingers in your body.”

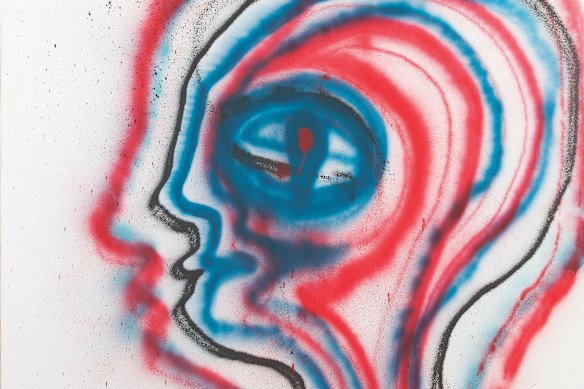

One of the central threads running through all the works is the spray can, which gave birth to contemporary graffiti culture in the 1970s. Spray cans are at once unremarkable, everyday tools and objects so dangerous that in your local Bunnings, they are locked away in cages.

In contrast to the brush, mark-making with a spray can largely removes the trace of the hand because the artist is not physically touching the surface. Skilled writers can also produce hard and soft edges by manipulating factors such as the distance from the wall.

“There’s also something very immediate and satisfying about it because it’s this air with paint particles that allows you to make a sweeping gesture quickly,” says Lowry.

Any discussion of graffiti has to encompass its transgressive, criminalised context, which is often all that outsiders see. It provokes strong emotions. Sydney Trains spends more than $30 million annually removing graffiti. There’s a NSW Graffiti Hotline dedicated to eradicating spray work, and in New York in the 1990s, catching writers and wiping out graffiti was the tip of the spear of then mayor Rudy Giuliani’s notorious “broken windows” policy.

Writing on walls can also have an outsized political effect. When Dave Burgess and Will Saunders painted the words “No War” on the Opera House sails in 2003 with massive red letters, it reverberated around the world.

Graffiti art also prompts questions of the ownership of public space and who gets to have a voice.

“I think a lot of writers don’t have a voice,” says Lowry. “I think it’s making some space for themselves in the world.

“More broadly, I hope Searches comes across as resisting the easy binary of ‘vandalism versus art’. It’s much more interested in questions of visibility, permission, public space and who gets to be seen.”

For Lowry, Searchers is also not strictly a show about graffiti in the narrowest sense.

“The project has always been more about the politics and poetics of spray: spray as a material and a visual language, and the way it moves between worlds – underground, suburban, cinematic, and contemporary art – carrying with it the charge of graffiti without being limited to it. Graffiti is central to that story, but it isn’t the whole story.”

Searchers: Graffiti + Contemporary Art is at the National Art School, Darlinghurst until April 11

Save

You have reached your maximum number of saved items.

Remove items from your saved list to add more.

From our partners