We recently covered a story on space debris here on the show, and the risks it can pose as it reenters the Earth’s atmosphere. The biggest concerns are largely the disruption to air travel, and possible damage to infrastructure. But there are maybe a million bits of space junk up there, and there are limits to our ability to track it. That said, Ben Fernando – a researcher at Johns Hopkins University – has a cunning solution: most incoming debris – initially doing up to 5 miles per second – is travelling so fast that it triggers sonic booms; these occur when the source of a sound wave is moving faster than the sound itself can, so it builds up into a massive shockwave. There’s enough energy in these sonic booms that, when they reach the ground, they can trigger the seismometers we deploy to detect earthquakes. Ben has been telling Chris Smith about his research…

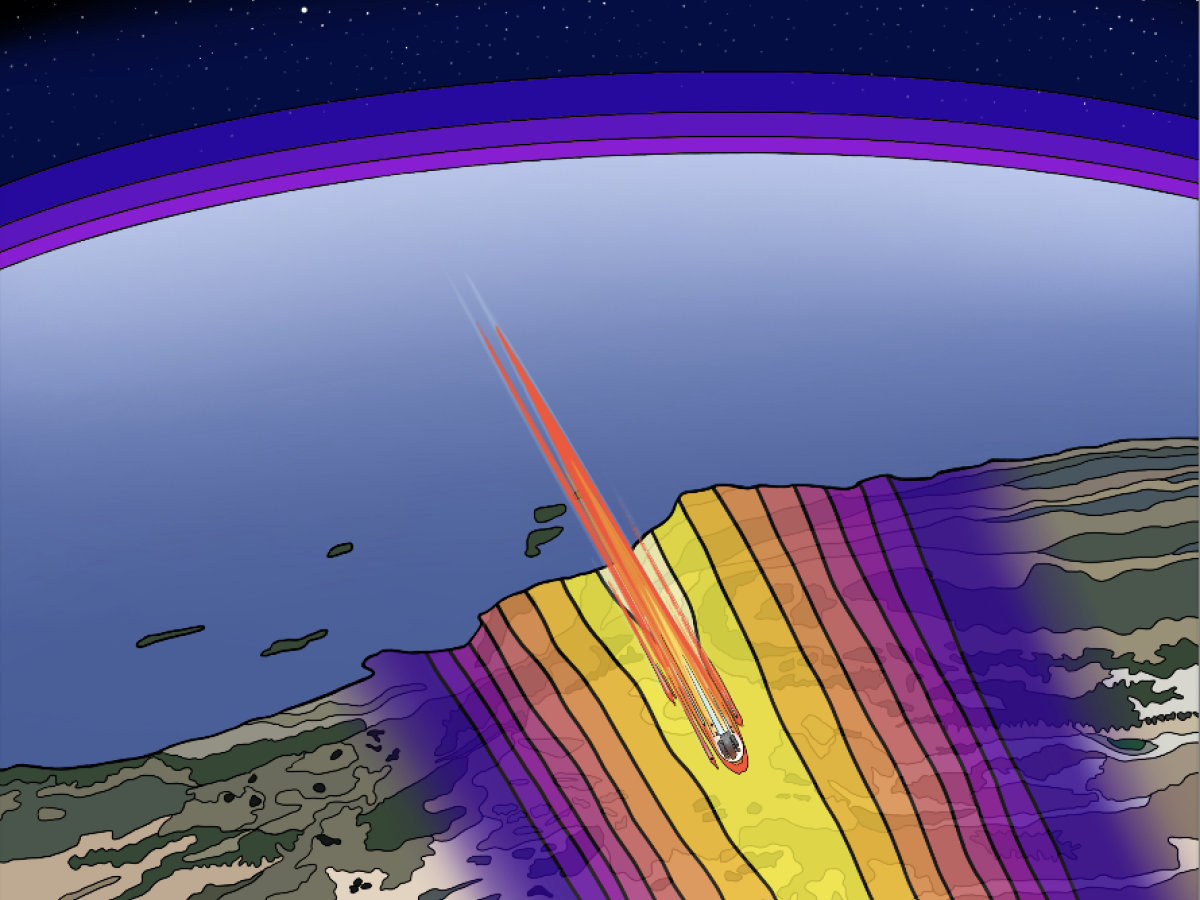

Ben – We now live in a world where we have multiple spacecraft re-entering the atmosphere in an almost entirely uncontrolled manner every single day. And the big issue for us is that a lot of these satellites contain pieces of debris that are toxic, or flammable, or even occasionally radioactive. But once they’re actually burning up in the atmosphere, it becomes very difficult to track them and figure out whether any fragments might have survived their passage through the atmosphere or indeed whether any fragments might have struck the ground. So we’re trying to work out new ways to track and characterise that space debris once it’s in what we call the terminal phase. So that phase where it’s burning up in the atmosphere to try and better understand the impacts it’s having on the atmosphere, and also the risks it’s posing to people in planes in the air, and on the ground.

Chris – Indeed, because we heard last week that one model suggests maybe there’s a nearly 30% chance of significant things coming down through some of the world’s busiest airspaces now. So this is a big issue, isn’t it? What sort of size of materials, though, are you interested in with this study?

Ben – In theory, anything that’s bigger than a few millimetres across should produce a sonic boom, a shockwave as it passes through the air. Whether we detect something that small is unclear, but certainly we’ve seen things that are a few tens of centimetres across. That’s a reasonably typical size for fragments of a piece of space debris once it started breaking up in the atmosphere. That might not sound very large, but if you imagine something the size of a football going five or six miles per second, that’s really not something you’d want punching a hole in the side of your aircraft fuselage, or indeed the roof of your house.

Chris – And you’ve hinted at your approach that these things are going so fast, they are well and truly breaking the sound barrier, and that is why you get sonic booms.

Ben – Exactly. So one of the issues is that radar tracking, which is what a lot of people do when stuff is in orbit, becomes a little bit more challenging once it’s in the atmosphere. But we have this big advantage that once the space debris, the spacecraft has entered the atmosphere, as you say, it’s going many, many times the speed of sound, and therefore it generates a sonic boom. That sonic boom propagates down to the ground. You could hear it if you were in the right place at the right time. But more importantly, for our purposes, it actually shakes the ground and shakes these seismometers, which are designed to detect earthquakes. And from that we can figure out what direction the debris was going in, how fast it was going, what angle it was descending through the atmosphere, and eventually how it broke up.

Chris – That’s amazing! So there’s enough energy being dissipated that vibration-sensitive devices to pick up earthquakes will actually see this?

Ben – Yes, it’s quite spectacular, really, when you think about it. These objects hit the top of the atmosphere going tens of thousands of miles per hour. A few minutes later, any pieces of debris are either completely burnt up or they’ve hit the ground, and they’re stationary. It gets incredibly hot. The surface of the debris will get to maybe several thousand degrees centigrade, and all of the rest of that energy is being dumped into the atmosphere. A lot of it goes into heat, but a not insubstantial portion of it is involved in this very complex process that generates a shockwave in front of it simply because the molecules of air basically can’t move out of the way in time.

Chris – And that sonic boom shockwave, that comes down to the ground, and presumably it’s going to tickle different seismometers at different times, and therefore you can work out roughly where it must have come from. You can triangulate its origin.

Ben – Exactly. So we see what we call a move-out pattern, which basically is a fancy way of describing the fact that different seismometers see the signal from the sonic boom at slightly different points in time. And from that, you can get both the speed and the trajectory, that is the direction, but also we can look at some of the real subtleties in that pattern and discern things like how steeply the debris is descending down through the atmosphere. So the fact that these different sensors see the shockwave at ever so slightly different points in time allows us to make some very detailed measurements of how this object is passing through the atmosphere.

Chris – I’m still awestruck that this works. How big is the displacement that the seismometers are picking up? I mean, compared to say an earthquake, it must be tiny.

Ben – It is tiny, but these seismometers are incredibly sensitive. So there’s a piece of debris which entered the atmosphere of California in April of 2024, and we see ground velocities, so up and down shakings, that are on the order of a few microns per second. That’s a few millionths of a metre per second. It might not sound like very much, but it’s enough that you might be able to feel it if you were standing there. It would be like being a few tens of kilometres away from an intermediate-sized earthquake. And the big advantage of these seismometers as well is it’s not just a person, it’s not just a feeling. We get really precise timing information as well, so we know down to the fraction of a second what time this wave arrived.

Chris – And how do you marry up that measurement with, ah, it was that bit of space debris?

Ben – Yeah, really good question. So what we do is we often try and correlate our seismic recordings with eyewitness accounts of people who both saw a fireball and also heard the shockwave themselves. The other thing that we can do is we know what orbit a particular piece of debris may have been in. We know it was going around and around the planet every, let’s say, 90 or so minutes. And so what we can do is, if we have a time and a location, we can try and work back to what piece of spacecraft that might have been, if that makes sense. So for this event, we saw a piece of space debris entering the atmosphere over California about one o’clock in the morning. We saw the seismic readings roughly the same time, and we knew that there was a Chinese spacecraft called Shenzhou 15, which was due to pass overhead a few minutes earlier. And we can kind of put those all together into one coherent picture of what’s caused this signal.

Chris – Can you do the same thing for non-man-made incoming objects? I’m thinking the things that cause shooting stars, debris, dust, other particles that may even turn into meteorites, things we can pick up on the ground.

Ben – Absolutely. And actually, that’s how we developed a lot of these techniques was for monitoring meteoroids, both on Earth and also on Mars as part of NASA’s InSight mission, which I was involved in. So we’ve actually taken some techniques that we developed for natural objects, that we developed for studying Mars, and turned them into something that we can use to study a real societally relevant problem here on Earth. And I also really like that as an angle to take on this, because it shows why that research on natural meteoroids was so valuable. We’re now applying it to study a really important growing problem here on Earth.