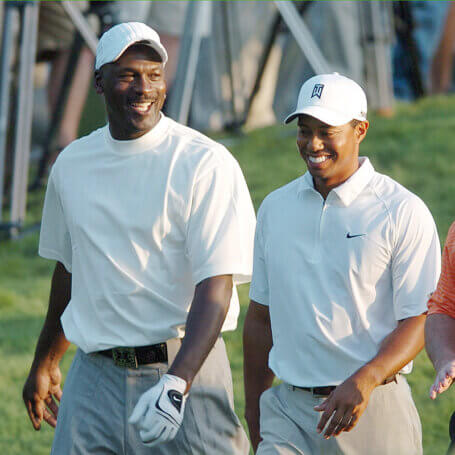

Michael Jordan and Tiger Woods in 2007 John D. Simmons, Charlotte Observer/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

Michael Jordan and Tiger Woods in 2007 John D. Simmons, Charlotte Observer/Tribune News Service via Getty Images

Nike is headquartered on a 400-acre campus in the city of Beaverton, a suburb of Portland. The property features 70 buildings, many of which are named after Nike athletes, among them Bo Jackson, Serena Williams and Ken Griffey Jr. Woods and Jordan, too. And the gyms, soccer fields, basketball courts and running trails that are interspersed around them are for the 11,000 employees based there to use before and after work and during lunch breaks. There is no dress code, per se, but it seems that whatever workers wear features the Nike logo. That includes sneakers and shoes, of course, though going barefoot is not discouraged. And one who has done that is Knight, the company’s 87-year-old chairman emeritus, who has been known to take meetings in his office without footwear.

He is also distinguished by the shield sunglasses he frequently dons and the scruffy, blond-red beard and mustache he usually sports.

Visitors to the Nike campus are easily awed by the positive energy that permeates. The sense of shared purpose and accomplishment is palpable, too. So is the loyalty employees feel toward the brand and the confidence and pride they exude.

Sometimes those sentiments border on hubris, as I discovered during several trips to Beaverton in the early 2000s and multiple interactions with Nike executives at major golf championships and PGA Shows in that period. One person who was particularly prone to that was a guitar-strumming, Birkenstock-wearing, F-bomb-dropping Californian named Bob Wood. One of the longer-standing employees at the time, having joined Nike in 1980, Wood was the architect of its move into golf and the first president of its golf division as well as the sport’s biggest advocate within the company. He frequently crowed about how Nike was going to bury the competition in equipment and dismissed the business skills and strategic thinking of some of the game’s most respected executives.

In some ways, that attitude was understandable given how the golf world reacted after Woods captured his first Masters in 1997 and four years later completed the Tiger Slam – and how invincible he and Nike suddenly seemed. And it was not just the tournament wins, for the company also received multiple awards for the clubs and balls it brought to market during that time.

It was also pure Nike.

Hubris, however, can cloud the judgment of even the clearest-thinking C-suiter. And most of the dozen or so sources I contacted for this article believe that it undoubtedly contributed to Nike’s lack of success in golf equipment.

… as welcome as Woods’ dominant play was, it sometimes gave the impression that he was so superhumanly talented it didn’t really matter what clubs and balls he used.

But they cited other reasons for that failure. Not fully appreciating how different the golf equipment sector was from apparel and footwear, for one. And how difficult it was to create and quickly build a business that could successfully compete with the game’s best-established brands, for another.

In addition, they pointed to a perception among serious golfers who, fairly or not, believed Nike lacked authenticity as an equipment maker.

To be sure, Tiger brought instant validation to the company when he started using its gear. But as welcome as Woods’ dominant play was, it sometimes gave the impression that he was so superhumanly talented it didn’t really matter what clubs and balls he used.

Finally, there was the fact that, according to Knight, Nike never made money in clubs and balls. To be sure, its golf division was profitable at times. But what Knight’s statements indicate is whatever Nike Golf cleared came from shoes and apparel.

So, Knight decided to focus that division instead on being the undisputed leader in golf footwear and apparel.

“In the end, it came down to Nike making better margins on a pair of socks than they did on a set of golf clubs,” said Tom Henderson, a PGA club professional and longtime elite Swoosh staff member who worked for more than three decades at the Round Hill Club in Greenwich, Connecticut.

Financial analyst Casey Alexander does not disagree with that assessment.

“Golf equipment is a brutal business,” he said. “It’s a steel cage death match for market share, and every few years, someone gets thrown out.”

Hughes Norton, the IMG executive who negotiated Tiger’s first contract with Nike and in the process came to know the company well, is among those who believes that hubris was indeed a problem.

“Nike has such an interesting culture,” he told Second Wind. “People there felt more like cult members than employees to me. There was a ‘We’re Nike, and you’re not’ attitude. To be honest, they had a lot to be arrogant about, for they were overwhelmingly successful and associated with many of the greatest athletes in the world. But with golf equipment, they were getting into an area that was completely different from shoes and apparel.”

David Pillsbury, who served as general manager for Nike Golf from 2002 to 2004, appreciates Norton’s comments.

“I enjoyed my time at Nike and admired the people there,” said Pillsbury, who has been CEO of Invited, the largest owner/operator of golf and country clubs in the U.S., since 2018. “But people sometimes acted as if all anyone had to do to create a successful product was slap a Swoosh on it and hire a great athlete to endorse it.”

Authenticity was also an issue.

Michelle Wie won the 2014 U.S. Women’s Open using Nike Golf equipment. Stuart Franklin, Getty Images

Michelle Wie won the 2014 U.S. Women’s Open using Nike Golf equipment. Stuart Franklin, Getty Images

“Nike had Tiger and a lot of the best players in the world wearing their logos on their shirts and hats, but they still had a hard time getting the hard-core golfer to play their clubs and balls,” said John Krzynowek, who in 1995 helped found and then run the market research firm Golf Datatech. “A lot of it had to do with Nike being a bit too avant-garde for the country club golfer and not a pure golf company like, say, Titleist or Ping. Also, Nike did not have a very strong relationship with green-grass golf professionals in the beginning because it was so new to the game. And those professionals are key influencers when it comes to getting golfers into a product or brand.”

Rory McIlroy won two majors in 2014 after signing with Nike Golf. Ramsey Cardy, Sportsfile via Getty Images

Rory McIlroy won two majors in 2014 after signing with Nike Golf. Ramsey Cardy, Sportsfile via Getty Images

It also did not help that Nike subcontracted its premium golf balls to an outside entity, in this case, Bridgestone. To be sure, what the Japanese concern provided Nike were top-of-the-line. But as word of that arrangement leaked out, many serious golfers found one more reason to doubt Nike’s authenticity. How could they not, the thinking went, if Nike had to go elsewhere to bring that critical product to market?

Others wondered whether Bridgestone would ever share its best technology with a competitor or react as quickly on their behalf to a development in the market.

Pillsbury well remembers dealing with the concerns about authenticity.

“In getting into golf equipment, the company may have underestimated just how entrenched brands like Titleist were with core-avid golfers at green grass,” he said of a group that tends to comprise older-generation, lower-handicap golfers who play more traditional brands. “One time, we invited a bunch of good golfers to an event in Los Angeles. All key influencers at their clubs, all with handicap indexes of 5 or below. We gave them the Nike One ball. They all played it and said they loved it. And we are thinking, ‘This is awesome.’ So, we asked, ‘Are you going to switch?’ And the answer was no. Not one person said they would change balls, and I think a lot of that had to do with their deep connections with Titleist.”

The mention of green grass reveals another hurdle that Nike had to clear when it got into balls and clubs, and that was dealing with a brave new business world. Nike had sold its shoes and apparel mostly through the off-course and sporting-goods channels. And purchasing in that area is generally consolidated within a single location. Like Dick’s Sporting Goods in Pittsburgh, for example, and PGA Superstore in Atlanta.

But the green-grass realm consists of thousands of different accounts all over North America, which take a lot more time and money to cover effectively. As a rule, those operations are staffed by PGA professionals who traditionally advise their members and players on the equipment they buy. And those roles became even more important to golfers – and made that channel more valuable than ever before – with the growth and evolution of club fitting in the latter part of the 20th century and the early 2000s.

Nike scrambled to establish a solid green-grass presence. In time, the company made strides in that area and developed a strong staff of professionals. Such as Henderson. And another notable PGA of America member, Eden Foster, from the prestigious Maidstone Club on the East End of Long Island. But Nike was never able to match the coverage that Titleist, Ping, Callaway and TaylorMade enjoyed in that channel or gain real traction among the golfers who did most of their shopping and buying there.

Another difference was in the ways the distribution channels worked – and worked to Nike’s detriment when it got into golf equipment.

“Take a big-box retailer like Dick’s,” said Pillsbury. “They would pay for a container full of shoes from Nike before the company even made them in Asia. But with green grass, the products are not paid for in advance, which means the manufacturer takes all the risk, with the golf professional not deciding how much gear he or she is going to buy until well after it has been made and shipped from the Far East.”

The challenges that Nike faced in building its green-grass presence were emblematic of its entire move into golf equipment. And that was getting good enough in just a few years to take on competitors who had been in the business for decades.

“And to do that successfully, you need to offer a product that is better or at the very least on par with the leading brands, and a strong and effective group of golf professionals who would help identify the green-grass target audience, facilitate the trial and sample process, and support the custom fitting platform,” said Wally Uihlein, who was president and CEO of the Acushnet Co., the parent of Titleist and FootJoy, for nearly two decades before stepping down from that position in early 2018. “Golf balls and golf clubs have always been green-grass driven.”

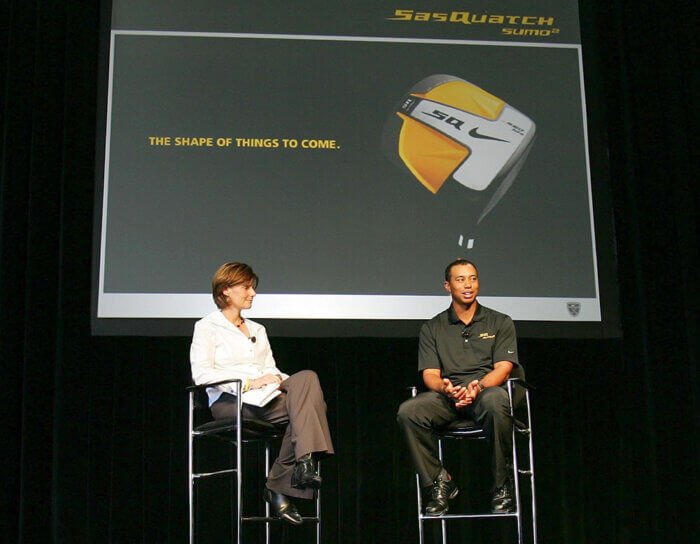

Cindy Davis and Tiger Woods Robert Laberge, Getty Images for Nike

Cindy Davis and Tiger Woods Robert Laberge, Getty Images for Nike

Davis appreciated the work that needed to be done.

“Golf was a whole new muscle for Nike,” she said. “It had never really been in the equipment business and was not servicing the specialty accounts, such as green-grass pro shops.

“It takes time to build and become credible in the equipment space,” added Davis, who served as Nike Golf GM from 2005-08, at which point she began a six-year run as president of that division. “But we were not naïve to that fact. We made investments, in the Oven, the golf club research and development facility we opened in Fort Worth [Texas] in 2002, and later a ball R&D facility in Beaverton. And in talent, too.”

Alexander speaks to that same issue when he states: “Golf equipment innovation builds on the innovation that comes before it. It stands on the shoulders of what a company has already done. And if you don’t have that base, that experience and the intellectual property portfolio that come from those things, then sometimes you are going to be shooting in the dark.”

There is also the matter of having the resources and managerial wherewithal to move quickly when introducing products and meeting the challenges that competitors present with their own new offerings.

Consider what happened with Nike and its Tour Accuracy ball in the spring of 2000. Woods surprised even his closest confidantes when he decided to make that switch, among them Devlin, who was Woods’ primary contact at the company, and the golfer’s caddie, Steve Williams. And that forced Nike to play catch-up as far as getting the ball to market and developing plans to market and sell it.

As for Titleist, it had been developing a solid-core ball of its own, dubbed Pro V1, in an effort that Uihlein has described as Acushnet’s version of the Manhattan Project. Titleist seeded that product among its staff professionals for the first time at the Invensys Classic in Las Vegas in September 2000 – and then brought it to retail in December, months ahead of its original schedule.

Only a company with the size, scope and experience of Titleist could have responded so quickly and completely to an advance by one of its competitors. And by doing so, it minimized the damage Nike might have done with Tour Accuracy and any advantages Nike might have gained with what was undisputedly a breakthrough product.

“We missed an opportunity when Titleist was able to do that,” said Devlin, who started working at Nike Golf in August 1998 and left in the winter of 2013.

“I have often wondered that if Tiger had been more open with us about the testing he had been doing with the product and his plans to switch to Tour Accuracy when he did, we might have been able to make that switch quicker,” he added.