James meant that in order to properly appreciate the game of cricket, one has to consider the historical and sociopolitical conditions under which the game is played. No contemporary writer proves this dictum more often or more thoroughly than the 59-year-old Australian Gideon Haigh, author of some of the finest cricket books of the 21st century, including The Big Ship: Warwick Armstrong and the Making of Modern Cricket (2001), Mystery Spinner: The Life and Death of an Extraordinary Cricketer (2002), On Warne (2012) and Sultan: A Memoir (2022, co-written with Wasim Akram).

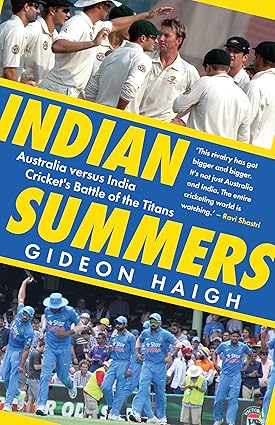

Westland has recently published his latest book, Indian Summers: Australia Versus India, a collection of essays covering what has grown to be arguably the foremost rivalry in contemporary cricket. These essays cover nearly a century of Indo-Australian cricketing encounters, starting with Frank Tarrant’s touring party of 1935-36 and going all the way till the 2024-25 Border-Gavaskar Trophy played in Australia. All the big, familiar moments for Indian fans—the 2001 Kolkata Test, the 2003 and 2023 ODI World Cup Finals, the 2024 T20 World Cup game—are covered here.

These big-game essays show both Haigh’s appetite for the ‘it’ moments, and his full suite of writerly skills. Today, it is common for critics to use the word ‘cinematic’ while talking about writers who’re brilliant at building dramatic tension with flair and visual details. But Haigh’s technique is more akin to classical theatre than to contemporary filmmaking (he quotes the Nobel-winning playwright and lifelong cricket nut Harold Pinter in a passage about Indian batter Cheteshwar Pujara). His essay about the 2001 Kolkata Test, for instance, drips with Shakespearean foreshadowing.

In a particularly striking passage, Haigh describes the over-confidence of the Australian team after day three of the five-day game—at this point, India was still trailing Australia’s score narrowly, with 4 second-innings wickets already down by the end of day three. While reading this passage (reproduced below), I could clearly visualize Steve Waugh, Michael Slater and Tony Greig in different corners of a large theatre stage:

“‘It’ll be over tomorrow,’ commentator Tony Greig said airily. ‘More time on the golf course.’ The Australians were of the same mind. Waugh eyed his Southern Comfort thirstily. Slater, who had nursed some reservations about the follow-on, playfully drew his cigar under his nose. ‘This result is so close I can smell it,’ he said, to the amusement of Gilchrist, who had not in his eighteen months as a Test cricketer known defeat.”

For me, though, where Haigh stands out from the crowd today is his clear-eyed diagnosis of cricket’s ongoing so-called ‘Big Three’ era, wherein India, England and Australia (and within them, mostly India) have hoovered up the lion’s share of global cricketing revenues, hosting rights and programming privileges. Haigh’s criticism of the BCCI is brutal (like a lot of writers inspired by Victoriana, Haigh is an experienced wielder of the acid tongue) and I would argue, relentlessly fair. Here he calmly and systematically dismantles the oft-parroted argument that as, the number one generator of revenue in world cricket, India is in fact entitled to the lion’s share (Ravi Shastri recently argued on Sky Sports that India is being underpaid by the rest of the cricketing world):

₹599″ title=”‘Indian Summers: Australia versus India—Cricket’s Battle of the Titans’: By Gideon Haigh; Westland; 352 pages, ₹599″>

₹599″ title=”‘Indian Summers: Australia versus India—Cricket’s Battle of the Titans’: By Gideon Haigh; Westland; 352 pages, ₹599″>

View Full Image

‘Indian Summers: Australia versus India—Cricket’s Battle of the Titans’: By Gideon Haigh; Westland; 352 pages, ₹599

“As is the case for every ICC member, India in international cricket is the creation of generations of tours and tournaments, of rivalries and reciprocities, fostered by the whole world. No country can accomplish anything on its own in international cricket, and every country contributes. Some, for reasons of economy and demography, cannot offer so much. The objective should always be to put a floor beneath and handholds beside the weakest because from a generally rising standard everyone benefits—I’d call it ‘levelling up’, had Boris Johnson not, like everything he ever touched, debased it.”

Haigh is brilliant at pairing cricketing logic with political commentary, and showing us how the dots between the two really connect in practice. In December 2023, the ICC objected to Australian cricketer Usman Khawaja sporting an illustrated dove on his cricket shoes during a game against Pakistan—to indicate his support for the children of Gaza. Haigh’s report at the time (on the website Cricket Et Al) was a masterclass in skewering hypocrisy. He pointed out the absurdity of the ICC’s ‘no politics’ veneer, given that several member countries’ cricket boards are officially headed by politicians from the respective ruling parties.

“For many years the world’s longest-running stage comedy was a farce called No Sex Please, We’re British, its jollity deriving from the idea that the more the characters tried to avoid the subject, the more they became implicated, and the greater the comic complications. Cricket has its own enduring counterpart: No Politics Please, We’re the ICC. Its hilarious premise is that the International Cricket Council is charged with preventing the game’s contamination by ill-defined but somehow always untoward political influence. This has now extended to…checks notes…a fucking dove.”

Indian Summers is a must-read for hardcore and casual cricket fans alike. It showcases the best of a man whose writings have described the game with wit, wisdom and humility for over three decades now.

Aditya Mani Jha is a Delhi-based journalist.