Executive summary

Few countries rely on their university sector as much as Australia does to power their national research and development (R&D). Australian universities perform over a third of the nation’s R&D overall — placing the country eighth among OECD members in 2020 for the share of research performed by universities, ahead of peers such as the United Kingdom (24%), France (21%) or South Korea (8%). Combined with their access to cross-disciplinary expertise and world-leading research facilities, universities anchor Australia’s sovereign research capability — delivering both vital R&D and strategic talent pipelines.

In this context, Australian universities have a leading role to play in the development of the AUKUS Pillar II Advanced Capabilities enterprise. This is apparent given that they produce internationally recognised research across all Advanced Capabilities workstreams, exhibiting particularly strong proficiency in the fields of quantum and hypersonics.

Yet, four years following the announcement of AUKUS, the Australian university sector’s contribution to R&D in support of Pillar II has been exceptionally modest. Despite their competitive edge in R&D and the large reserves of innovation power, both specific AUKUS-related constraints, as well as broader systemic challenges facing Australia’s R&D landscape, have continued to obstruct universities’ ability to contribute to Pillar II.

It is against this backdrop that this brief makes the case for greater university involvement in driving and cultivating the Innovation, Science and Technology (IS&T) ecosystem needed to realise AUKUS Pillar II objectives.

To date, two structural realities shaping Australia’s R&D have limited university involvement and stunned its innovation ecosystem. First, the Australian Government has not recognised the full scope and potential of university-based R&D outputs — both for defence imperatives and for the economy writ large. This has contributed to their omission from key AUKUS initiatives, constraining their role in shaping AUKUS-related R&D. Second, over the past fifteen years, Gross Expenditure on R&D (GERD) in Australia has declined to strikingly low levels, reaching a slim 1.68% of GDP, well behind the OECD average of 2.7%. Largely driven by a fall in government investment in R&D as a share of GDP and a decrease in large business investment in R&D, this has hampered Australia’s already limited national capacity to translate basic research into higher Technological Readiness Levels (TRLs).

Given Australia’s limited size and capacity compared to its AUKUS partners, it is imperative that Australia enacts a whole-of-government approach to R&D to catalyse a sustained, self-reinforcing cycle of Defence-related innovation that supports its AUKUS obligations and ambitions.

At universities, the drop in GERD has been exacerbated by the soaring costs of research as well as a siloed and fragmented government R&D funding landscape. This has added to historically low levels of funding for experimental research and of industry-research collaboration — undermining the potential for universities to advance R&D into deployable solutions and in turn, permeating Australia’s efforts to nurture a Defence IS&T ecosystem.

Moreover, these various pressures assume a distinctive character in AUKUS and broader defence-related academic research because of universities’ role in society and in the economy. First, the needs of defence and security-based research often collide with some traditional academic principles around approaches to transparency and institutional autonomy. Second, they require navigating university-specific challenges, such as academic career incentives and trajectories, or even the social license within institutions to conduct defence-related R&D.

Together, these challenges have hindered engagement between Defence and academia. While mechanisms and schemes do exist for universities to engage in AUKUS Advanced Capabilities workstreams, they remain disjointed, poorly mapped and embedded within a declining R&D landscape. As a result, the Australian Government has forfeited opportunities to leverage a key national strategic capability, limiting universities’ readiness to lean into AUKUS Pillar II R&D.

The net result is that Australia is far from being an ‘innovation nation’ or an ‘innovation economy’. The Australian R&D ecosystem, and in particular the university research sector, is not fit for purpose. The lack of government investment, coordination and recognition of the value of the sector mean that Australia is not well placed to execute the AUKUS enterprise. Given Australia’s limited size and capacity compared to its AUKUS partners, it is imperative that Australia enacts a whole-of-government approach to R&D to catalyse a sustained, self-reinforcing cycle of Defence-related innovation that supports its AUKUS obligations and ambitions.

In an era of strategic competition dominated by new technology areas such as AI, quantum, and automation — all AUKUS Pillar II areas — Australia is at grave risk of being left behind by the developed world.

Recommendations

1. Strengthened governance and strategic coordination of the R&D landscape

The Australian Government should adopt a whole-of-government approach to R&D and signal clear research priorities and opportunities for universities to embrace and deliver Pillar II-related R&D. This will require leveraging and accelerating existing coordination mechanisms, such as the Australian Defence Science and Universities Network (ADSUN) and the nascent Defence Research Centres (DRCs), to streamline coordination and prioritise focused and impactful R&D.

2. Improved engagement between Defence and universities

The Australian Government should build upon and enhance its engagement with universities. This includes strengthening outreach through classified briefings, innovation working groups and joint committees to align academic expertise with Defence priorities.

3. Increased and optimised funding for R&D

The Australian Government should increase and strategically align public and private R&D to meet OECD standards, as well as optimise funding mechanisms to bolster efficiency in support of AUKUS Pillar II R&D.

4. Embedded incentive structures and mechanisms

Both the Australian Government and the university sector should review incentive structures to encourage Defence-related R&D. This includes streamlining security clearances, rewarding classified research, and demonstrating value in universities adopting safeguards — in accordance with Defence standards — to conduct defence-related R&D.

DownloadAustralia’s innovation, science and technology environment: Providing a rationale for universities’ contributions to AUKUS Advanced Capabilities

AUKUS Advanced Capabilities and Australia’s innovation imperative

In April 2024, Australian, UK and US Defence Ministers reaffirmed AUKUS Advanced Capabilities as a critical engine to power Defence-related innovation, aimed at “pooling the talents of our Defence sectors to catalyse, at an unprecedented pace, the delivery of advanced capabilities.” This statement, coming four years after the establishment of AUKUS, is evidence that this ambitious defence technology pact is still yet to assume its place as a cornerstone of Australia’s approach to accelerating its Defence innovation. With most of the attention so far focused on Australia acquiring a conventionally armed, nuclear-powered submarine (SSN) capability, AUKUS Pillar II remains relegated to second-tier status and characterised as “a solution in search of a problem.”

According to the defence leadership of the three countries, Pillar II charts a path forward to integrate the defence and technology innovation ecosystems of three nations to effectively deliver “capabilities that will matter most in the future.” Despite this design function, with unclear demands from AUKUS governments and no definitive ownership or bespoke budget for implementation, the scope and dimensions of Pillar II have been amorphous to date. Instead, progress has been overwhelmingly focused on creating the enabling legislative and regulatory environment for the sharing of sensitive technologies. What limited direct action has been confined to exercises and science experiments rather than capability development. One of the key limitations to Pillar II’s development has been the ability of the three countries to simultaneously design and deliver classified military capabilities while deriving benefit from an open innovation landscape and commercial partnerships. Consequently, trilateral cooperation under AUKUS Pillar II has been reduced to specific, siloed projects, limiting its broader ambition to harness national research and innovation strengths to accelerate capability development at cost.

First Assistant Secretary AUKUS Advanced Capabilities Stephen Moore during Exercise Talisman Sabre 2025. Source: Australian Department of Defence

First Assistant Secretary AUKUS Advanced Capabilities Stephen Moore during Exercise Talisman Sabre 2025. Source: Australian Department of Defence

Despite implementation limits, across all three countries, the rationale for Pillar II remains exceptionally clear: the race for critical technologies is now a key terrain for global and regional strategic competition. With China arguably commanding leadership in published research in 17 of the 23 critical technologies identified for strategic competition -— including in AUKUS priority areas of hypersonics, electronic warfare and autonomous underwater vehicles, and sonar and acoustic sensors — Pillar II holds the potential for AUKUS partners to gain a technological edge, creating pathways to cross-fertilise their R&D and elevate their R&D profile globally as well as tap into their partners’ R&D resources. With the US budget for defence-related Research, Development, Test and Evaluation (RDT&E) for FY2025 valued at US$145.1 billion — some four times Australia’s entire Defence budget that year — Pillar II provides a unique opportunity for Canberra to leverage the comparatively larger R&D budget of its AUKUS partners.

In Australia, both the 2023 Defence Strategic Review (DSR) and the 2024 National Defence Strategy (NDS) recognise the imperative for a robust Defence innovation ecosystem. Both of these strategic documents position AUKUS Pillar II as a catalyst for a strategically focused Defence R&D effort. Australia’s loss of strategic warning time and the spectre of major power conflict prompted the DSR to shift the country’s posture from managing low-level threats to deterring great power conflict in the Indo-Pacific through a strategy of denial — underpinned by, among other elements, advanced technologies and integrated capabilities. The subsequent 2024 NDS elevated IS&T as one of the seven broader initiatives key to national Defence — propelling a A$3.8 billion investment in the Advanced Strategic Capabilities Accelerator (ASCA) “to translate asymmetric technologies into Defence capability” and identifying AUKUS as a launchpad for a force integrated by design.

Crucially, both the DSR and the NDS recognise cross-sectoral engagement and cooperation across Australia’s landscape to be vital to achieving AUKUS Advanced Capabilities goals. The NDS positions AUKUS as “a step change in Australia’s ability to enhance cooperation with partners, industry and academia to rapidly develop and introduce technologically advanced military capabilities into service.” Accordingly, at the core of the Defence’s 2024 Defence Innovation, Science and Technology Strategy (Defence IS&T) is a 10-year vision to accelerate innovation to develop capability through the mobilisation of Australia’s IS&T community and the harnessing of the AUKUS partnership.

Australia’s universities, by dent of their national role in R&D, should stand at the heart of this effort. Collectively, they conduct 36% of Australia’s total R&D, well above rates reported by OECD countries — where levels of university research as a share of national research stand at 24% for the United Kingdom, 18% in Germany or 12% in Japan. They harbour world-class facilities and cultivate a highly skilled talent pipeline, uniquely positioning them as a core part of Australian national power and a strategic asset for National Defence. Crucially, Australian universities are already conducting world-leading research in AUKUS Advanced Capability areas, with Australia ranking among the world’s top five nations for high-impact quantum research and patents and home to some of the most advanced hypersonics programs worldwide. Yet, despite explicit references to academia in the DSR, NDS and Defence IS&T strategy, in practice, the potential for universities to accelerate IS&T for AUKUS Advanced Capabilities remains an unrealised capability for Australia’s defence efforts.

Furthermore, Defence’s efforts in IS&T are hamstrung by a lack of national focus and direction. While the Australian Government lauds Australia’s innovation record and recognises the need to transform the economy and kick-start productivity, it is doing so while actively marginalising the university sector’s research efforts and overseeing a prolonged, bipartisan decline in gross expenditure on R&D (GERD). These critiques are hardly new — as of 2025, the Australian Government has launched two major reviews into research undertaken in Australia, including the Universities Accord Process and the Strategic Examination of R&D (SERD). Yet, despite longstanding calls for reform, the national IS&T is wallowing, with no visible overall strategic approach to research.

Amid intensifying strategic competition, a national productivity crisis and rising criticism of Pillar II’s lacklustre performance, there is growing urgency for Australia to deliver large-scale investments into IS&T through revitalised investments in GERD, a coordinated and focused whole-of-government strategic approach to research investments and a sovereign and robust Defence ecosystem. For Defence, this will require bringing universities into the AUKUS Pillar II tent.

Why involve universities in AUKUS Pillar II innovation?

Though most Australian research universities surpass Defence’s in-house research and innovations investments in overall research size and scale, universities have yet to be assigned a clear role in contributing to AUKUS Pillar II. No Australian research institution was successful under the AUKUS Innovation Challenges, the flagship trilateral ‘contests’ launched by AUKUS governments to develop and identify rapid, cutting-edge defence tech capabilities. Instead, significant AUKUS-related IS&T investments have been primarily channelled through industry-Defence collaboration, focused on more mature and market-ready technology, rather than the lower Technology Readiness Levels (TRLs) pathways associated with university research. For example, the much-lauded AUKUS-adjacent defence project ‘Ghost Shark’, Australia’s extra-large autonomous undersea vehicle (AUV-XL), noted for its flexibility and faster-moving pace, was developed by defence innovation company Anduril in collaboration with the Royal Australian Navy (RAN) and targeted higher TRLs outcomes.

Though most Australian research universities surpass Defence’s in-house research and innovations investments in overall research size and scale, universities have yet to be assigned a clear role in contributing to AUKUS Pillar II.

Yet, Australian universities are well-equipped to become an indispensable stakeholder in the Defence R&D system needed to deliver AUKUS Advanced Capabilities. They conduct 87% of the country’s discovery or basic research, reflecting their central role in advancing early-stage R&D at lower TRLs and filling a critical gap before industry takes concepts to higher maturity levels. They also directly fund half of the country’s applied research, surpassing peer countries, with French and South Korean universities funding 14% and the United Kingdom 30%. Moreover, central to breakthroughs such as the development of wi-fi, solar technology, the cochlear implant or quantum computing, Australian universities have earned a strong global reputation for world-class research, specifically in discovery science. In 2021, this contributed to the US Air Force Office of Scientific Research — through its Asian Office of Aerospace Research and Development (AOARD) — and the US Office of Naval Research Global (ONRG) to establish a presence in Australia, with Jermont Chen, the AOARD director, stating “The purpose is to cross-pollinate and to leverage each other. They can leverage our funding, and we can leverage their knowledge of the area…”

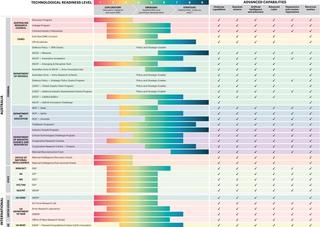

At the helm of those advocating for a stronger role for universities in both Defence R&D and the AUKUS Pillar II is the Group of Eight (Go8), which convenes Australia’s eight leading research-intensive universities. Go8 estimates in 2022 suggest its constituent universities invested almost A$70 million into Defence R&D annually, representing some 44% of the total university sector investment. These collectively hold expertise across all AUKUS Advanced Capabilities and have signalled their interest in leaning into the trilateral partnership. With this scale and research leadership, the Go8 alone offers a breadth of capability spanning frontier technologies and enabling areas such as supply chain resilience, ethics and Defence policy for the Australian Government to tap into to foster a robust Defence innovation ecosystem.

Table 1. Grid showing AUKUS Pillar II capability across the Group of Eight universities

Beyond its immediate discovery role, the Australian university sector’s value proposition to the AUKUS enterprise extends to purpose-built technical facilities, hubs for interdisciplinary knowledge, workforce development and global academic exchanges. Australian universities are home to publicly funded world-class research infrastructure and facilities, open to universities, industry and government. This access to shared infrastructure not only allows Defence, primes and SMEs to innovate without significant capital investment but also lowers barriers of entry, accelerates innovation, and delivers both national security and broader societal benefits. Further, the sector serves as an engine room for cross-disciplinary knowledge and innovation. Uniquely positioned to integrate expertise across engineering, science, medicine, business, and policy, it provides Defence with access to an aspect of innovation that industry alone cannot generate. Australian universities are also pivotal to developing the workforce needed for AUKUS Pillar II and to serve Defence capability priorities writ large. At the cornerstone of education, they have the capacity — nationally and in partnership with UK and US counterparts — to develop expanded pathways through work-integrated learning, industry partnerships and targeted scholarships to train the next generation of AUKUS engineers, scientists, inventors, entrepreneurs and policy specialists.

Moreover, various recent case studies make clear the burgeoning opportunities for university-led discovery research to mature into Defence- and commercial-deployable solutions in line with allied Defence and technology priorities. For example, both Australia’s Jindalee Operational Radar Network (JORN) and Sydney-based Advanced Navigation company illustrate how academic inputs can support the development of sovereign capabilities, underpinning Australia’s defence. Both brought to fruition with contributions from university R&D, today, JORN provides the country with a long-range over-the-horizon radar, while Advanced Navigation provides fibre-optic gyroscope navigation systems for Defence export programs.

Recognising this potential, the Australian Government has launched targeted initiatives, such as the Australian Economic Accelerator (AEA) and the Trailblazer Universities program, to accelerate university-led Defence IS&T into higher TRLs (7–9). AEA, a A$1.6 billion program, provides funding to translate and scale academic research into commercial and deployable solutions. The Trailblazer Universities Program, a A$370.3 million initiative to be delivered between 2022 and 2026, focuses on enhancing institutional research capacity by embedding both large-scale cross-sectoral engagements and a commercialisation culture within universities. Both attest to ongoing governmental attempts to encourage the development of an innovation pathway by incentivising collaboration with industry, supporting open Intellectual Property models and rewarding commercial outcomes. Still, the paucity of these initiatives, spread too thin across many areas, let alone AUKUS Advanced Capabilities, restricts their large-scale impact on Defence innovation. Already oversubscribed, these initiatives would require a more deliberate focus on Defence priorities, backed by greater funding, to create a systemic bridge that consistently translates lower-TRL defence research into deployable capability.

1. Universities face an underfunded and fragmented R&D landscape1.1. Australia falls short of international standards for GERD

For Australia to capture the full spectrum of opportunities presented by AUKUS — from maximising access to world-class research in the United States and the United Kingdom to staying globally competitive in the race for advanced technologies — it should continue and increase meaningful investment in R&D.

In terms of research outputs, Australia’s efforts are truly laudable. In the well-used Australian adage, the nation’s research sector ‘punches above its weight’. Australian research contributes to 3.5% of the world’s publications and makes up 5.8% of the world’s citations. Crucially, its impact is demonstrable, with Australian research cited 42.2% higher than the world average. This has been achieved, though, amid an Australian research sector in significant decline.

US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, Australian Deputy Prime Minister and Defense Minister Richard Marles and British Defence Secretary John Healey met at the Pentagon in December 2025. Source: Getty

US Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, Australian Deputy Prime Minister and Defense Minister Richard Marles and British Defence Secretary John Healey met at the Pentagon in December 2025. Source: Getty

Although R&D is well known to strengthen national growth, reportedly generating an average return of A$3.50 to economy for every A$1 invested in R&D, Australia has not adopted strategies to leverage its R&D landscape for social or economic benefits. Even the much-heralded Treasury-led “Economic Reform Roundtable” report in 2025, which focused on lifting productivity, failed to address or recognise universities’ R&D contribution in its discussion around innovation and technology writ large — let alone with respect to Defence. In fact, it only references the university sector once and only when recognising its role in strengthening human capital to contribute to the Treasury’s priority to “Build a skilled and adaptable workforce” through the Universities Accord.

Beyond policy parsimony, the numbers that articulate the sector’s decline are telling.

Australian overall investment in R&D as a proportion of GDP has been on a downward trajectory over the past fifteen years, with 2022 spending levels estimated to be some 32% lower than in 2008. In 2021-2022, GERD was estimated at A$38.8 billion, or 1.68% of GDP — far below the OECD average of 2.73% of GDP and leaving Australia short of A$25.4 billion per year across all sectors.

1.2. Mapping Australia’s shortfalls in national investment in R&D

The decline in GERD in Australia is attributed to a fall in government and business investment in R&D as a share of GDP. Government expenditure in R&D (GovERD) has decreased from 0.27% of GDP to 0.16% between 2008 and 2022, while Business expenditure on R&D (BERD) has fallen from 1.37% to 0.9% of GDP during this same period. This means Australia’s BERD is about half that of its OECD peers. This persistent underinvestment undermines Australia’s capacity to commercialise its research, weakening its long-term technological competitiveness and constraining the development of sovereign industrial and Defence capabilities.

Figure 1. Total government R&D support as a percentage of GDP

To further understand Australia’s R&D landscape, three considerations warrant attention. First, while GERD has declined overall, nominal R&D expenditure — including the business, government, higher education and private non-profit sectors — has consistently risen across all sectors between 2001 and 2022. However, these increases in nominal terms have both lagged behind GDP as well as fallen relative to industry output. The latter reflects a long-term decline in business research intensity, now at a twenty-year low despite BERD in Australia reaching a record A$20.6 billion for 2021-2022.

Figure 2. Expenditure on R&D by sector (A$ millions)

Expenditure on R&D by sector as a percentage of GDP

Second, while Australian investment in basic and applied research is at comparable levels to that of other OECD countries, investment in experimental development is where the country falls behind. This largely stems from limited research-industry collaboration as well as low and declining levels of large business investment in IS&T. In Australia, while 44% of Australian businesses innovate, fewer than 10% of Australian firms collaborate with universities. Further, with Australian large firms contributing some 45% of BERD, versus the OECD average of 61%, declining levels of investment by large companies in research blunts Australia’s delivery of innovation outputs and constrains R&D’s multiplier effects. This is critical — no OECD country sustains a strong IS&T ecosystem without substantial investment from large businesses.

Third, irrespective of funding levels, government investment in R&D lacks strategic coherence, with current responsibilities for defining research priorities dispersed across more than a dozen government portfolios. Despite numerous reviews of the research sector and policy initiatives, national research priorities have had minimal bearing on Australia’s research profile, many R&D investments have remained underfunded, and efforts to strengthen industry-university cooperation have had minimal impact. With 84% of Commonwealth R&D investment channelled through ‘bottom-up funding models’, the remaining ‘purpose-led R&D’ funding — provided in support of clear and articulated strategic priorities — is dominated by grants. According to the seminal ‘Strategic examination of Australia’s R&D system’, this creates a “subscale” and “disjointed” system, diluting the scope and scale of IS&T investments and eroding IS&T stakeholders’ innovation potential. This differs from Australia’s peers, such as the United States, Germany and South Korea, where funding models are comparatively “more strategically directed and intentional, led by national agencies or specific strategies.”

1.3. Funding pressures have spurred the emergence of a university funding model reliant on foreign investment

In universities, the impact of declining GERD and segmented, unstable GovERD have been compounded by the soaring costs of conducting research and overall diminishing government funding. For every dollar of research grant investment from the Australian Government, universities have to invest an additional 35% in infrastructure and overheads “just to keep the lights on” — let alone to nurture a thriving and future-driven R&D enterprise.

Over the past three decades, funding pressures have incentivised universities to cushion the fallout from government policies that have decreased public investment in the sector with alternative sources of revenue. This includes international student fees. Both sides of politics’ readiness to cross-subsidise Australian research through a pipeline of full-fee-paying international students has effectively created a funding model that directly ties Australia’s sovereign research capability to foreign funding. Notwithstanding the risks associated with exposing Australia’s research sovereign capability to global market shocks, this has given rise to a funding model where IS&T stakeholders are driven by different strategic imperatives.

As a result, despite performing over a third of the country’s overall R&D, Australian universities face a patchy, resource-constrained R&D landscape, characterised by silos and competing priorities, obstructing visibility of available opportunities, funding streams and initiatives to conduct research in areas of strategic interest. This undermines their potential to embrace high-impact, high-visibility research projects and constrains their ability to plan, scale and sustain long-term research.

2. Impediments facing defence-related R&D mirror those facing Australia’s R&D landscape2.1. Gaps in R&D funding have cascaded into Defence’s IS&T landscape

The Defence-related IS&T landscape very much echoes Australia’s research landscape — resource-constrained, fragmented, insufficiently integrated with industry, with university-led R&D’s potential to advance defence priorities largely untapped. In fact, Defence is not cited once among Australia’s National Science and Research Priorities, which, released in 2024, provide the Australian Government’s primary guidance to align efforts and investment in science and innovation over the next decade. Instead, “critical technologies such as artificial intelligence (AI), quantum and robotics” are referenced only in the context of the net-zero transition.

Further, though Australia’s Department of Defence increased its R&D budget share from 2.6% to 2.73% in 2024, it still trails behind its AUKUS counterparts. In 2023-2024, the United Kingdom allocated approximately 3.9% of its total Defence budget to R&D, with plans to increase this to 7% in the next few years, while the United States reportedly allocated some 17%. Crucially, despite government statements and policy documents framing Pillar II R&D as a priority, Australia has not provided dedicated funding, systemic support or embedded incentive mechanisms to spur research for Pillar II. According to Professor Tanya Monro, Chief Defence Scientist and head of the Defence Science and Technology Group (DSTG), this is somewhat deliberate — AUKUS Pillar II is not intended as a standalone funding stream for working trilaterally, but rather as a mechanism to leverage respective national strengths and to deliver improved opportunities for IS&T stakeholders to contribute to multilateral defence-related research efforts. In 2024, she explained “There is no pot of gold at the end of the rainbow for people who Aukusise their R&D.” In practice however, the lack of a distinct, transparent ‘Pillar II-only’ budget line, along with the absence of enabling structures and mechanisms to underwrite such research, has limited traction in AUKUS Pillar II.

Defence is not cited once among Australia’s National Science and Research Priorities, which, released in 2024, provide the Australian Government’s primary guidance to align efforts and investment in science and innovation over the next decade.

In Australia, the impact of a lack of dedicated funding for AUKUS Pillar II research needs to be viewed within the wider national context of prolonged overall declining investment across the R&D system as a share of GDP and low levels of BERD. This has contributed to businesses’ offshoring the development of vital Australian security and Defence R&D capabilities. From a national security perspective, this has left Australia reliant on foreign innovation and industrial ecosystems to access core capabilities, heightening risks that domestic needs would compete with other nations’ priorities in the event of a contingency.

In response, the Australian Government has introduced a suite of policy levers designed to stimulate Defence-related BERD and strengthen sovereign capability, such as the Australian Industry Capability (AIC) Program, which requires major Defence contractors and foreign prime suppliers to demonstrate how they will maximise Australian industry participation, technology transfer and workforce development across their supply chains. The AIC now aligns with the broader framework of the Sovereign Defence Industrial Priorities (SDIPs) set out in the Defence Industry Development Strategy, which identifies critical industrial capabilities essential to national security. Complementary initiatives such as the Global Supply Chain (GSC) Program, focused on connecting local firms with global primes and integrating them into international Defence value chains, have secured A$2.35 billion in contracts for more than 307 Australian suppliers. Nonetheless, these mechanisms have yet to reverse Australia’s low business R&D intensity. Australian SMEs still lack the necessary scale to translate R&D into deployable outputs, while prime Defence contractors prefer to both carry out a proportion of their Defence R&D outside Australia and favour in-house capability development, rather than externally-commissioned research.

2.2. Pathways for Defence-related R&D for Australian universities exist, but require greater strategic coherence and visibility

Beyond funding pressures, the Defence-related R&D landscape underpinning AUKUS Innovation in Australia has inherited many of the issues stemming from the country’s fragmented research landscape. While Australia harbours a diverse portfolio of existing research and innovation mechanisms that align with AUKUS Pillar II, the absence of a whole-of-government approach has created an unwieldy Defence R&D landscape, causing inefficiencies, silos and duplication that hamper both progress and accountability. At a university level, this fragmentation fosters confusion around which and where clear pathways exist for researchers to tap into Defence-related R&D funding, as well as blurs clear direction on priority areas to focus on. This sets up a strong initial disincentive to prioritise Defence-related research.

With research funding and activity spread across multiple agencies and jurisdictions, the sheer complexity of mapping out the different priorities and institutional mechanisms available to universities to conduct Defence R&D — and by extension to contribute to AUKUS Pillar II objectives — is a case in point of the complex and fragmented nature of Australia’s IS&T landscape. The following section provides an overview of existing programs, offering greater visibility into the interdependencies, gaps and silos that currently constrain coordination and coherence across the ecosystem in addition to highlighting real opportunities.

Opportunities available to universities via the Australian Department of Defence

DSTG, ASCA and the Groups and Services innovation arms serve as the three leads for the Defence IS&T Enterprise. Despite DSTG’s role as the main conduit for and partner of university research, along with its strategic commitment to align R&D with AUKUS Pillar II technology streams, there is still uncertainty and a lack of clarity over how universities can access relevant research opportunities for Defence research or support AUKUS Pillar II research.

Similarly, ASCA, Defence’s primary agency to accelerate capability delivery to the ADF through innovation, has a mandate spanning the innovation pathway from TRL 1 to 9. Within the context of Pillar II, ASCA is recognised as playing “an important role … [with] key technology themes relevant to AUKUS workstreams (hypersonics, trusted autonomy, quantum technology and information warfare)” as well as the Australian lead in the AUKUS Innovation Challenges. Nonetheless, though ASCA’s mandate includes collaboration with universities, in practice, it has largely engaged with industry partners, given its primary focus on transitioning prototype and disruptive technologies into acquisition pathways and minimum viable capability for the ADF.

Australian Minister for Defence Industry Pat Conroy and Chief Defence Scientist Professor Tanya Monro AC at the Indo Pacific International Maritime Exposition, November 2025. Source: Australian Department of Defence

Australian Minister for Defence Industry Pat Conroy and Chief Defence Scientist Professor Tanya Monro AC at the Indo Pacific International Maritime Exposition, November 2025. Source: Australian Department of Defence

Universities can further access relevant Defence research funding opportunities via the Groups and Services, such as the Australian Army Research Centre and the Navy’s Autonomous Warrior exercise, as well as establish collaborations, such as the Jericho Smart Sensing Laboratory (JSSL) between RAAF Plan Jericho and the University of Sydney. However, communication of these opportunities is not centralised, nor is there a platform where they are systematically listed, or explicitly linked to AUKUS Pillar II. This hampers visibility and access — limiting universities’ participation and undermining overall transparency.

Other relevant funding schemes and pathways

These strategies, programs and agencies represent a sample of funding streams and mechanisms arising from Defence. To these, should also be added relevant grants from the Australian Research Council (ARC), CSIRO, the Office of National Intelligence, the Department of Industry, Science and Resources (DISR), the Department of Education or state governments, as well as overseas schemes — where eligibility extends to Australian academia — notably from the US Department of Defense, Intelligence Advanced Research Projects Activity (IARPA) and the UK Defence and Security Accelerator (DASA). Though each of these initiatives may not be explicitly designed for AUKUS Pillar II, they offer further support in translating basic science programs into commercial applications. Together, they attest to the availability of schemes relevant to AUKUS Pillar II across the discovery, translation, industrialisation and policy domains, and suggest there is overall sufficient coverage for the advanced capability areas.

Yet, the absence of unifying mechanisms and coordination means that pathways to accessing funding for both academia and industry are not always straightforward, visibility is scarce and fragmentation systemic. While there can be benefits from a decentralised system — in the main, creating greater flexibility for diverse ideas and greater innovation to flourish — in Australia, the lack of scale, coupled with scattered government and industry support, leaves university-led R&D opportunities unrealised and sometimes discontinued.

The range of mechanisms discussed is summarised in Figure 3, highlighting the breadth of Australia’s research and innovation programs relevant to Defence and AUKUS Pillar II, while revealing an ecosystem that remains dispersed and difficult to navigate.

Figure 3. Snapshot of the Innovation Pathway Ecosystem for Australia, relevant to AUKUS Pillar II

i. AUKUS partners’ counterparts for the AUKUS Innovation Challenge include the United States Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) and the United Kingdom Defence and Security Accelerator (DASA). Disclaimer: This dataset is indicative only and based on publicly available sources. Some assessments are approximate or inferred and should not be regarded as official classifications. While the table shows most schemes as covering all six AUKUS Advanced Capability domains, in practice, many programs (such as ARC Discovery or CRCs) are not Defence-specific. They are broad, open-ended funding mechanisms that may support Defence-relevant advanced capability projects, but do not guarantee such outcomes.2.3. Defence is on track for better engagement with universities, but needs acceleration

i. AUKUS partners’ counterparts for the AUKUS Innovation Challenge include the United States Defense Innovation Unit (DIU) and the United Kingdom Defence and Security Accelerator (DASA). Disclaimer: This dataset is indicative only and based on publicly available sources. Some assessments are approximate or inferred and should not be regarded as official classifications. While the table shows most schemes as covering all six AUKUS Advanced Capability domains, in practice, many programs (such as ARC Discovery or CRCs) are not Defence-specific. They are broad, open-ended funding mechanisms that may support Defence-relevant advanced capability projects, but do not guarantee such outcomes.2.3. Defence is on track for better engagement with universities, but needs acceleration

In response, Defence has sought to reinforce collaboration and engagement with the university sector by establishing various integration mechanisms to strengthen workforce, networks and expertise. For example, DSTG’s NAVIGATE program is proactively embedding external researchers — mostly from academia — within Defence on fixed-term placements to expose them to Defence priorities and accelerate the translation of academic and industry expertise into capability — an initiative that could be leveraged and expanded within AUKUS Pillar II partners to foster joint innovation and skills exchange.

Further, under the 2024 IS&T Strategy, Defence is updating the existing Australian Defence Science and Universities Network (ADSUN), Defence’s vehicle to socialise its research priorities and broker relations between research stakeholders at the state level via co-funded nodes, to become a “highly visible and effective national mechanism.” The strategy also foreshadows the establishment of Defence Research Centres (DRCs), recognising the need for long-horizon, university-anchored hubs linking Defence scientists, industry and end users. Analogous to US University Affiliated Research Centres (UARC) models, these DRCs would serve to consolidate research around Defence-defined missions, effectively shifting universities’ role from independent discovery toward sustained, directed partnerships focused on capability outcomes.

Though laudable, both mechanisms would benefit from greater clarity. Currently, with each ADSUN node holding its own governance and funding arrangements, ADSUN 2.0 seeks to establish a more cohesive and integrated national framework. While better anchoring ADSUN in the wider Defence ecosystem is necessary, for greater impact, ADSUN 2.0 needs to address current challenges related to resourcing and enablement, fragmented engagement across states, and uncertainty around goals or measurable deliverables in accordance with Defence priorities. At present, there is also limited clarity on coordination between ADSUN — which links Defence with universities — and Office of Defence Industry Support (ODIS) — which connects Defence with industry — risking lost opportunities to align research, innovation and commercialisation pathways across the Defence ecosystem. Meanwhile, concrete direction, funding opportunities and timely implementation for DRCs remain lacking to date. While existing collaborative university-defence centres, such as the Centres for Advanced Research in high-frequency technology (CADR-HF Technologies), in Chemical, Biological, Radiological, and Nuclear conditions (CADR-CBRN), or in robotics and autonomous systems, may provide some indication as to how DRCs will be modelled, ambiguity around timelines, funding streams, models and mechanisms underpinning these centres has resulted in little further direction and undermined overall transparency. Finally, as per the IS&T strategy, Industry are poised to play a role in DRCs; however, their distinct priorities from universities — seeking Intellectual Property (IP) generation, market access, with shorter-term revenue cycles rather than research excellence or reputation — will necessarily require tailored co-investment and IP frameworks to balance these differing goals.

2.4. Fragmentation of Defence IS&T opportunities inhibits effective Defence-university engagement

Beyond impeding the delivery of meaningful research, this fragmentation of the research landscape drives unhelpful competition between universities, exacerbates disconnects between Defence and universities and other research institutions and limits visibility of academia’s potential contribution to Defence R&D. The plethora of short-term funding programs and contracts in particular lessens strategic misalignment between Defence and universities, resurfacing tensions between Defence’s preference for de-risked, scalable solutions vs academia rewarding depth of expertise, while adding administrative complexity through disparate mechanisms, overlapping timelines, reporting requirements and priorities.

While universities are central to Australia’s discovery research base, Defence is not able to fully capture universities’ expertise and potential in their efforts to deliver effective capabilities into the hands of the ‘war fighter’ — with university-led research on health or the environment to increase national resilience, for example, being overlooked despite having Defence applications.

Together, chronic underinvestment and lack of clear innovation pathways have fostered siloed and arguably calcified partnerships between the university and Defence sectors. From a whole-of-government standpoint, this erodes cross-sectoral connectivity and mutual literacy between Defence and academia, exacerbating existing wedges and creating inefficiencies. As a result, while universities are central to Australia’s discovery research base, Defence is not able to fully capture universities’ expertise and potential in their efforts to deliver effective capabilities into the hands of the ‘war fighter’ — with university-led research on health or the environment to increase national resilience, for example, being overlooked despite having Defence applications. In turn, universities grapple to articulate how their work aligns with Defence needs — at once hindering and obscuring their potential contribution to the AUKUS Advanced Capabilities enterprise. Cognisant of these challenges, both DSTG and ASCA have initiated outreach with universities, engaging with senior university leadership and convening classified briefings.

Despite some progress, sustained and additional engagement is needed to overcome decades-long underinvestment and reduced industry-defence-university focused collaboration. For AUKUS Pillar II, this limited cross-sectoral connectivity at the national level is compounded by the inherent coordination and practical challenges in conducting trilateral Defence-related research at universities, from navigating three sets of tertiary education bureaucracies and legislative frameworks, to aligning different budget cycles, to balancing competing priorities.

3. Universities face both shared and distinct AUKUS-related challenges

Although a complete analysis of AUKUS-related challenges lies beyond the remit of this brief, universities, too, are faced with the barriers now associated with AUKUS, such as navigating export controls, coordinating vetting processes and streamlining compliance requirements across three nations. These challenges assume a distinct form in academia, intersecting with principles of academic freedom, transparency and institutional autonomy.

Compliance with export controls provides an illustrative example. In Australia, universities must adhere to the Defence Trade Controls Act and the Defence Strategic Goods List, which regulate sensitive technology transfers when conducting Defence-related R&D with international partners. In 2023, reform discussions around definitions of ‘fundamental research’ alone were indicative of the complexity in applying export controls to university research. Similarly, a set of barriers relates to the intersection of security obligations, compliance requirements and the realities of the academic workforce. For universities to engage in sensitive or classified Defence research, they are often required to maintain membership in the Defence Industry Security Program (DISP), which entails stringent standards and significant administrative costs. Academics, in turn, generally require a security clearance from the Australian Government Security Vetting Agency (AGSVA). These — restricted to Australian citizens and involving complex vetting processes — pose a structural challenge for a sector where a sizeable segment of academics are born overseas.

Compounding these challenges are the incentive structures of academia, where career advancement has traditionally depended heavily on accessible publication. Defence research, by contrast, often restricts public dissemination to protect sensitive outcomes, creating a tension between operational security and academic aspirations. This renders long-term engagement less attractive or realistic for many researchers without appropriate sector-wide mechanisms to recognise their R&D contributions. Even in instances when universities have sought to provide alternative career advancement opportunities (i.e. appointment of ‘professor of practice’ positions), publications and citations too often remain as key criteria used to assess eligibility for scholars to receive funding through traditional research agencies. Similarly, academia rarely rewards partnerships or translational outcomes, neglecting to incentivise engagement with industry. This misalignment stifles sustained engagement in Defence R&D. Discussions from USSC roundtables suggested that limited funding, restrictive conditions and misaligned university KPIs had led major university faculties to reduce participation in Defence-related research despite the promised opportunities arising from AUKUS Pillar II.

Lastly, universities must balance strengthening government trust with maintaining social licence to conduct Defence-related research. First, perceived as vulnerable to information breaches, universities are required to demonstrate strong security cultures and safeguards for classified work. ASCA’s leadership has reportedly raised concerns around universities’ ability to manage sensitive dual-use research, citing reliability, security culture and exposure risks. Concurrently, some academics and members of the public have historically expressed scepticism around universities conducting Defence-related R&D, based on preconceived negative views of defence research or concerns around academic independence, commercial and government pressures, workforce values or lack of transparency, to name a few. These concerns resurfaced across some university campuses in 2025 amid wider conversations around universities’ investment portfolios and partnerships, with student protests condemning the militarisation of the university sector, prompting major Australian universities to reconsider their investments in Defence and security-related industries.

Case study: Re-establishing AUSMURI as a low-hanging fruit for AUKUS Pillar II

The Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative (MURI) is a long-standing US Department of Defense (recently renamed the Department of War) program that funds university discovery research at low TRLs across areas such as quantum, autonomy and advanced materials. It remains active in the United States and is widely regarded as one of the most effective mechanisms for linking discovery research to long-term Defence capability as well as enhancing critical mass by partnering universities together on identified Defence challenges and priorities. Alongside the core US program, bilateral extensions have been created with partner countries to allow joint participation. These include initiatives such as UKMURI and AUSMURI, which enabled foreign universities to collaborate directly with US counterparts on MURI-funded topics.

Australia’s involvement came through the Australia-US Multidisciplinary University Research Initiative (AUSMURI), a nine-year, A$25 million program supported by the Next Generation Technologies Fund (NGTF), which was matched by the US Government to bring the total value of the initiative to around A$50 million. AUSMURI allowed Australian universities to engage in US-defined MURI topics, with individual projects able to receive up to approximately A$1 million per year for three years.

However, with the establishment of ASCA, DSTG confirmed that AUSMURI is no longer open, with existing contracts now managed within ASCA. The program demonstrated how bilateral funding can connect low-TRL discovery research with Defence capability outcomes, and its closure comes at a time when Australia, the United States and the United Kingdom are seeking practical models to operationalise AUKUS Advanced Capabilities research.

Reinstating AUSMURI would represent a pragmatic, high-impact win for Australia under AUKUS Pillar II, reviving a proven bilateral mechanism that strengthens allied research linkages and positions Australian universities at the forefront of discovery-to-capability pathways, leveraging the existing, impactful US MURI program as a foundation mechanism for bilateral, and potential trilateral, innovation.

Recommendations

For Australia to fully capitalise on the AUKUS enterprise and establish a robust IS&T system that drives continuous innovation, Australian R&D stakeholders should consider the following recommendations:

1. Strengthened governance and strategic coordination of the R&D landscape

The Australian Government should adopt a whole-of-government approach to Defence-related R&D. The Australian Government requires a genuine strategic approach to Defence IS&T — one that recognises its integral contribution to both AUKUS and the Australian Government’s productivity agenda more broadly, outlines clear direction and priorities with commensurate funding streams, as well as provides clear incentives to spur BERD in Defence, including AUKUS and AUKUS-adjacent advanced capabilities.

Defence should clearly signal the research opportunities and priorities at which universities should lead, support and invest in, as well as where they could further collaborate across the Defence IS&T ecosystem.

Defence should uplift and adequately resource the Australian Defence Science and Universities Network (ADSUN 2.0) to act as the central coordination and communication framework linking Defence, universities and industry across states and territories, in close alignment with the Office of Defence Industry Support (ODIS). This includes establishing consistent national governance, clear objectives and metrics, and a unified approach to funding and engagement, ensuring alignment with the broader Defence IS&T ecosystem and AUKUS Pillar II priorities.

Defence should accelerate the establishment of Defence Research Centres (DRCs) with dedicated funding, transparent pathways and governance in parallel with set priorities aligned to Defence challenges and possibly AUKUS Pillar II Advanced Capabilities. Models should accommodate the distinct roles of government, universities and industry to foster enduring, outcome-focused collaboration and positioning in the ecosystem.

Defence should clearly signal the research opportunities and priorities at which universities should lead, support and invest in, as well as where they could further collaborate across the Defence IS&T ecosystem.

2. Improved engagement between Defence and universities

Defence should sustain and increase its classified briefings to universities. These briefings are vital for universities to gain a clear understanding of Defence priorities and problem sets — a critical enabler for developing coherent innovation and commercialisation pathways aligned with operational capability requirements. Early communication on timings and location for these briefings is further essential, as is a considered effort to ensure they are held across the different states and territories.

Defence should convene an ‘Innovation Working Group’ to improve universities’ understanding of the ADF’s operational needs while leveraging academia’s leading technical expertise. The Australian Government should model such working groups on the Army’s Land or Maritime Environment Working Groups to engage with scholars and R&D stakeholders with and without a security clearance.

Defence and the university sector should establish a joint government and university committee for Pillar II R&D, convening senior Defence officials and university leaders. Academic leaders, positioned at the forefront of emerging technology trends, could also serve as a standing pool of expertise to support government in identifying and assessing new and disruptive technologies, complementing Defence’s internal capability.

3. Increased and optimised funding for R&D

The Australian Government should lift GovERD and incentivise higher BERD levels for GERD to at least match the OECD average in R&D spending.

The Australian Government should streamline a cross-agency strategic approach for research funding writ large to support AUKUS Advanced Capabilities. With limited scale and funding, Australia cannot meet AUKUS Advanced Capabilities objectives without coordinating and streamlining funding across its government agencies.

The Australian Government should embed collaborative R&D requirements and incentives within existing programs to increase private investment in research partnerships, improving national innovation performance and supporting advanced capabilities (e.g. through the Australian Industry Capability Program, Global Supply Chain Program (Defence/CASG), the Industry Growth Program (DISR) or the Defence Industry Development Grants Program (Defence/CASG).

Defence should clarify pathways available to translate basic R&D into applied research. This entails mapping existing research opportunities as well as points of interface between industry, the Australian Government and universities.

4. Embedded incentive structures and mechanisms

The Australian Government should streamline security clearances for Australian researchers and innovators. Vetting processes for university stakeholders focused on advanced capabilities research areas should be prioritised.

Defence should conduct systemic engagement with universities to support institutional readiness for universities to contribute to AUKUS Pillar II. This includes ongoing engagement to ensure all elements of AUKUS Pillar II priorities, incentives, schemes and regulatory requirements are known and understood.

Universities, collectively and individually, should establish clear academic recognition and reward pathways for researchers conducting classified Defence research. Universities should create forms of recognition — such as distinctions or fellowships — rewarding researchers’ contribution to AUKUS Advanced Capabilities proportionate to the complexity and importance of the R&D.

Legacy research funding agencies should broaden assessment criteria to include classified defence research career recognition. This includes the Australian Research Council and the National and Medical Research Council. The use of citations and publications as the chief basis for funding selection disincentives classified Defence research and risks overlooking impactful recipients.

Universities should establish and communicate clear safeguards to conduct classified Defence-related R&D. Universities need to demonstrate to the Australian Government that they have appropriate mechanisms to safeguard their Defence-related R&D. Clear guidance and institutional support need to be provided to university staff seeking to pursue Defence-related research.

The Australian Government should provide clear guidance and associated funding streams around safeguards needed for universities to conduct Defence-related research. For universities to fully lean into Defence-related research, they require greater clarity and support to access appropriate facilities and implement appropriate security mechanisms for classified research.

Universities should enhance institutional mechanisms that facilitate industry collaboration and research commercialisation, including simplified IP and contracting processes, targeted partnership funding and structured support for spin-offs.

This brief is funded with support from the US State Department.