Speaking on Matt Stephens’ podcast, Riccitello was blunt about how he races. “During races, I basically do not use a power meter or heart rate monitor at all,” he explained. “I do not look at them to make decisions. After the race, I do check it. In training, I do look at the numbers again, but not during races themselves.”Racing by feel in a numbers era

That distinction matters. Riccitello is not rejecting data outright. He trains with it, analyses it afterwards and understands its value. What he resists is allowing numbers to dictate decisions in the heat of competition.

That philosophy runs counter to the system that has defined elite stage racing for more than a decade. The rise of Team Sky and later INEOS reshaped the peloton. Power meters moved from optional tools to essential equipment. Mountain pacing became pre-planned. Effort was managed, capped and controlled. Riding without numbers in a Grand Tour GC role became almost unthinkable.

Riccitello’s Vuelta was a reminder that another path still exists. On the penultimate day, he finished sixth on the Bola del Mundo, one of the race’s most unforgiving climbs. He did so without a power meter on the bike. “There were quite a few days at the Vuelta where I did not even have a power meter on my bike. Purely to make the bike a bit lighter,” he said. “On the Bola del Mundo, someone asked me how much power I had pushed on that climb. I was like, no idea.”

It is not bravado. It is intent. “I am interested in data, and I do use it in training,” Riccitello added. “But in races, I do not think it is very crucial to have those numbers.”

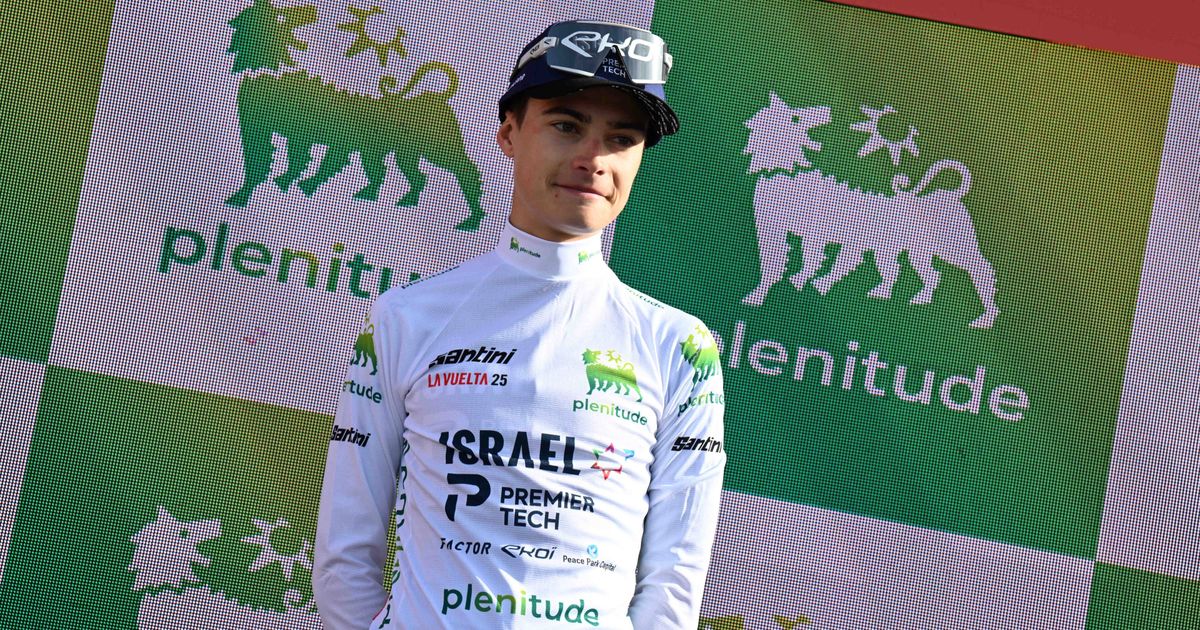

A young rider with an old school edge

That mindset places Riccitello in a small modern minority. Pre-Sky era racing was not anti-science, but it allowed instinct to guide in race decisions. Riders learned limits in real time rather than calculating them in advance. Feel, not wattage ceilings judged attacks.

Riccitello’s strength aligns neatly with that approach. He has described his ability to absorb repeated efforts as a core asset, and it is why Grand Tours appeal most. The longer a race lasts, the more it suits him. Fifth overall in Madrid was not framed as an endpoint, but as a starting marker.

For Decathlon CMA CGM, the appeal is obvious. A climber capable of surviving and thriving deep into a three-week race, yet unshackled enough to respond when the road rather than the screen demands it.

Cycling has not abandoned data, and it never will. But Riccitello’s success suggests the sport has not eliminated space for feel, either. In a peloton still living in the shadow of Team Sky’s legacy, that balance might be his quiet edge.