A certain vintage of football fans might turn their nose up at the ever-changing football lexicon, but when discussing a team’s out-of-possession approach, we are now firmly in an era of… the block.

Previously, a defensive team looking to frustrate an opponent might be referred to as “sitting deep”, but the early noughties saw Jose Mourinho introduce the phrase ‘parking the bus’ when describing a compact shape without the ball.

Liverpool head coach Arne Slot’s continued frustration of coming up against a “low block” has rippled through the Premier League after becoming a theme in the downfall of their title-defending season.

“To create chances against a low block, you need pace, individual special moments to create an overload,” Slot said at the start of January.

“You don’t see a lot of 15-20-pass goals against low blocks. Another way is to create a counter-attack or win the ball high up the pitch when they want to bring the ball out from the back.”

By Slot’s measure, overcoming an opposition “low block” can be achieved by having a coherent “high block” yourselves — leading to more high regains, which traditionalists might prefer to term as simply “closing the opposition down”.

(Ben Stansall/AFP via Getty Images)

You get the picture.

While they might now be executed with greater physical intensity and tactical accuracy, we have seen these defensive set-ups for decades. Terms might change, but the principles have largely been the same.

What is different is our ability to measure these out-of-possession approaches at scale with sharper tools. Using SkillCorner’s “phases of play” model — which extracts contextual metrics from broadcast tracking — we can break down each facet of the game when a team does not have the ball.

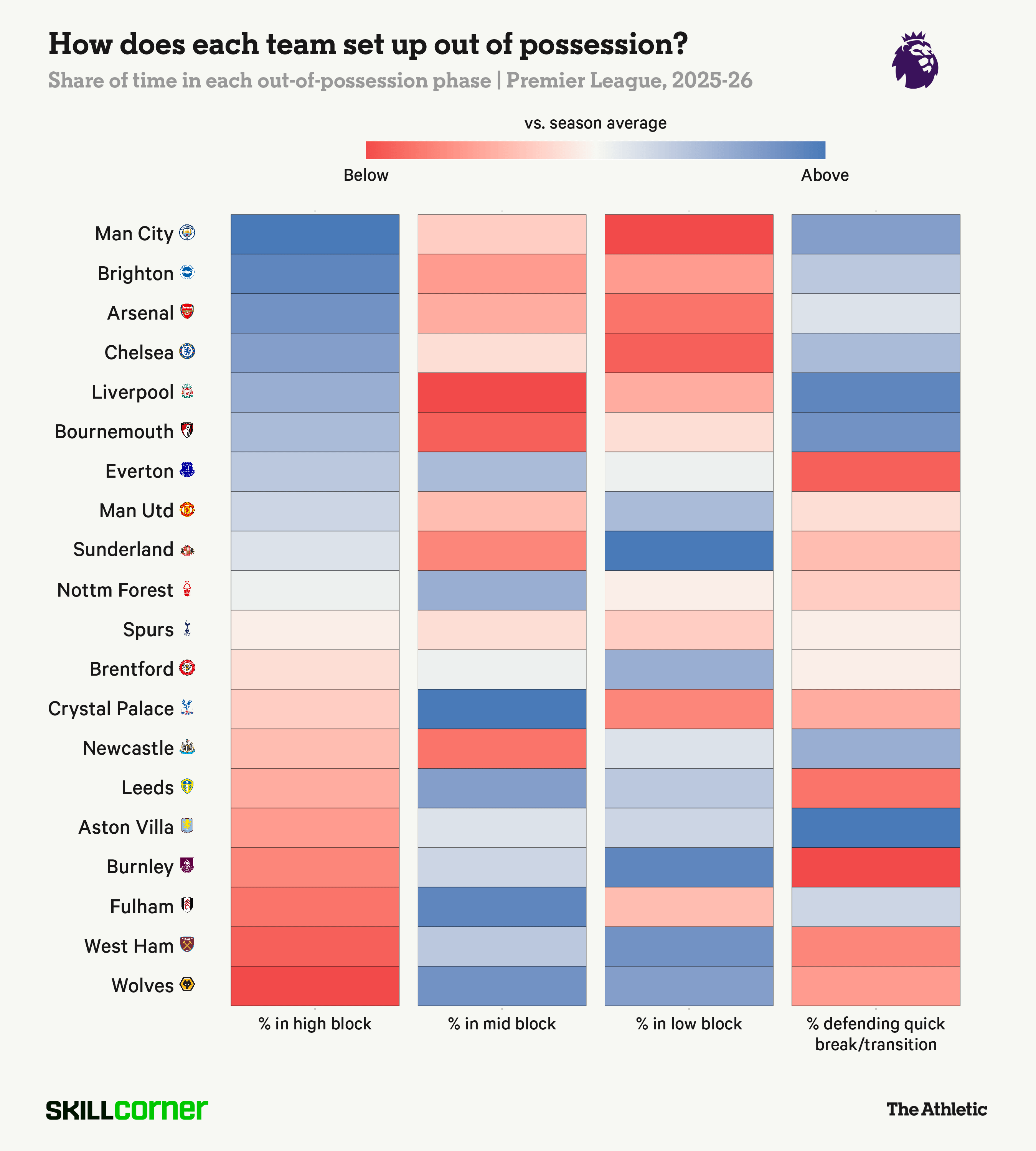

Here, we distinguish between three key blocks. A ‘high block’ sees a team engaging with the opposition when they have the ball in their own defensive third. A ‘mid block’ is denoted by the average position of the deepest three defensive players being within the middle third. Finally, a ‘low block’ is denoted by the average position of the deepest three defensive players being within their own defensive third.

Manchester City’s 23 per cent of time spent in a high block is the largest share in the Premier League, edging ahead of title rivals Arsenal and struggling Brighton & Hove Albion (20 per cent).

Oliver Glasner’s Crystal Palace have the highest share of time spent in a mid block (44 per cent), while newly-promoted Sunderland are the most likely to fall back into a low block (30 per cent).

City’s share of time spent in a high defensive block is hardly surprising when considering their in-possession style that still hinges — albeit less than in previous years — on territorial dominance.

However, their defensive approach goes beyond simply counterpressing when they lose possession. Since Guardiola’s assistant Pep Lijnders arrived this summer, City have been more measured in how they squeeze the pitch, with certain triggers to lock onto the opposition during build-up, including loose or backwards passes.

An example of this can be seen during their home game against Brighton at the start of January. As Lewis Dunk collects the ball from the corner of the pitch, City push up their high block and go man-for-man to cut off any passing options — with Erling Haaland staying central between the width of the goal frame.

Dunk’s long ball is immediately cut out by defensive midfielder Nico Gonzalez, who releases Haaland with a first-time pass as City regain possession high up the field.

This pattern was almost identical for City’s second goal in their recent away game against Tottenham Hotspur. Similar to the example above, right-back Matheus Nunes has gone all the way into the final third to man-mark the opposition forward, with all options cut off by City’s player-for-player press.

Radu Dragusin’s hopeful ball is intercepted by Rodri, who swiftly releases into a similar space for Bernardo Silva to square the ball to Antoine Semenyo, who finishes past Guglielmo Vicario.

While Slot’s comments suggest that teams are spending more time defending deeper this season, there is no evidence to suggest that a higher share of out-of-possession time is spent in a low block.

Perhaps his grievance lies more in the growing efficiency of the division’s defensive units, with a compactness that leaves fewer opportunities for forward-thinking players to flex their attacking muscles.

Using SkillCorner’s data, we can map the average height and width (in metres) of each side’s defensive structure when playing in a low block. By this measure, high-flying Sunderland are not only the most active in their share of time in a deeper shape, but are the most compact when scaling the average area of that low block.

Sunderland’s home form has been particularly strong, being one of only six sides in Europe’s top five leagues to be undefeated in their own stadium — an exclusive list that includes Napoli, Juventus, Borussia Dortmund, Paris Saint-Germain and Barcelona.

Part of that success has been built on solid defensive foundations, with only Arsenal and Manchester City (eight) having conceded fewer at home than their nine goals at the Stadium of Light.

Regis Le Bris’s side started the season with a back-four system but introduced a back-five set-up at the end of October, with Sunderland able to switch between the two formations depending on the strengths of the opposition — not unlike the success that Brentford had upon their promotion under Thomas Frank in 2021.

As shown below against Burnley, a compact 5-4-1 is both narrow in width and tight in depth — leaving no space to play through and forcing the opponent into wide areas.

With their forwards dropping in to support the cause defensively, Le Bris has previously batted away concerns that this can lead to greater bluntness in attack.

“If you think that every phase is important for the outcome of a game, confidence can be built through this defensive shape,” Le Bris said in late December.

“Our forwards, our wingers are really important in this part of the game, even if they can often use their energy. They are doing really well so far. Obviously, you need good centre-backs and a strong goalkeeper and so on, but it is a great team effort.”

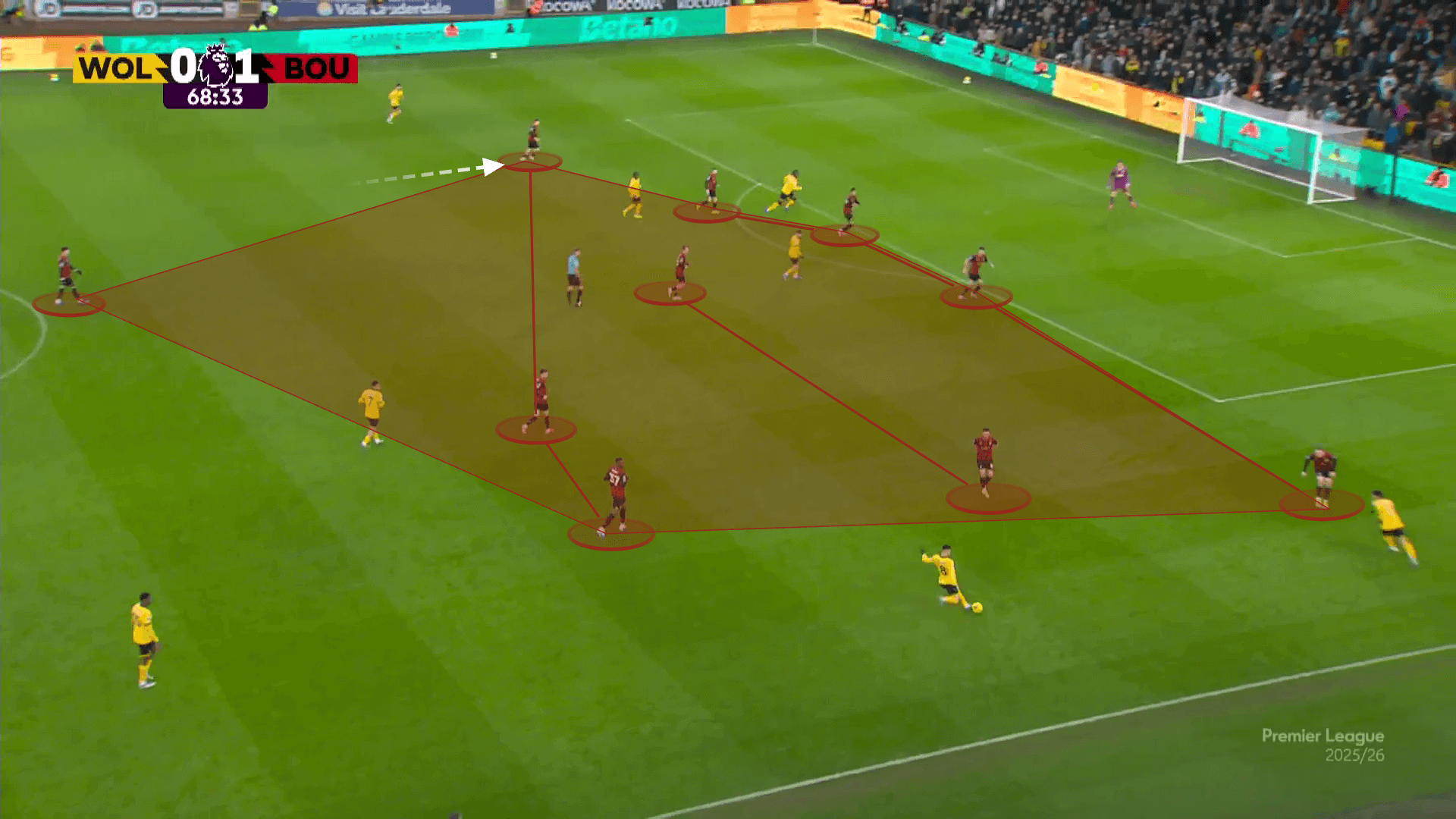

By contrast, it makes sense that Bournemouth are the least compact when defending in a low block. Their relentless press has subsided a little since last year, but Andoni Iraola’s side still look to get touch-tight to their opposite number rather than sit back and give up territory by camping on the edge of their own box.

This was shown in their recent away trip to Wolves. Here, Alex Jimenez (playing as a right forward) drops in to form a back five out of possession, but Bournemouth’s coverage across the pitch is notably wider as the cross comes in — with the depth spanning from the edge of the penalty area to Evanilson on the edge of the centre circle.

Bournemouth’s results have picked up in recent weeks, but their style will always have more of a chaotic style, as their manager confesses.

“I think we are quite proactive with the ball and without the ball,” Iraola said in a recent interview.

“Normally, our games are quite open; we are one of the teams who score more goals and one of the teams that receive more goals. I would like to score more than we receive, but I feel we are closer to a result if we are always a threat to the opposition.”

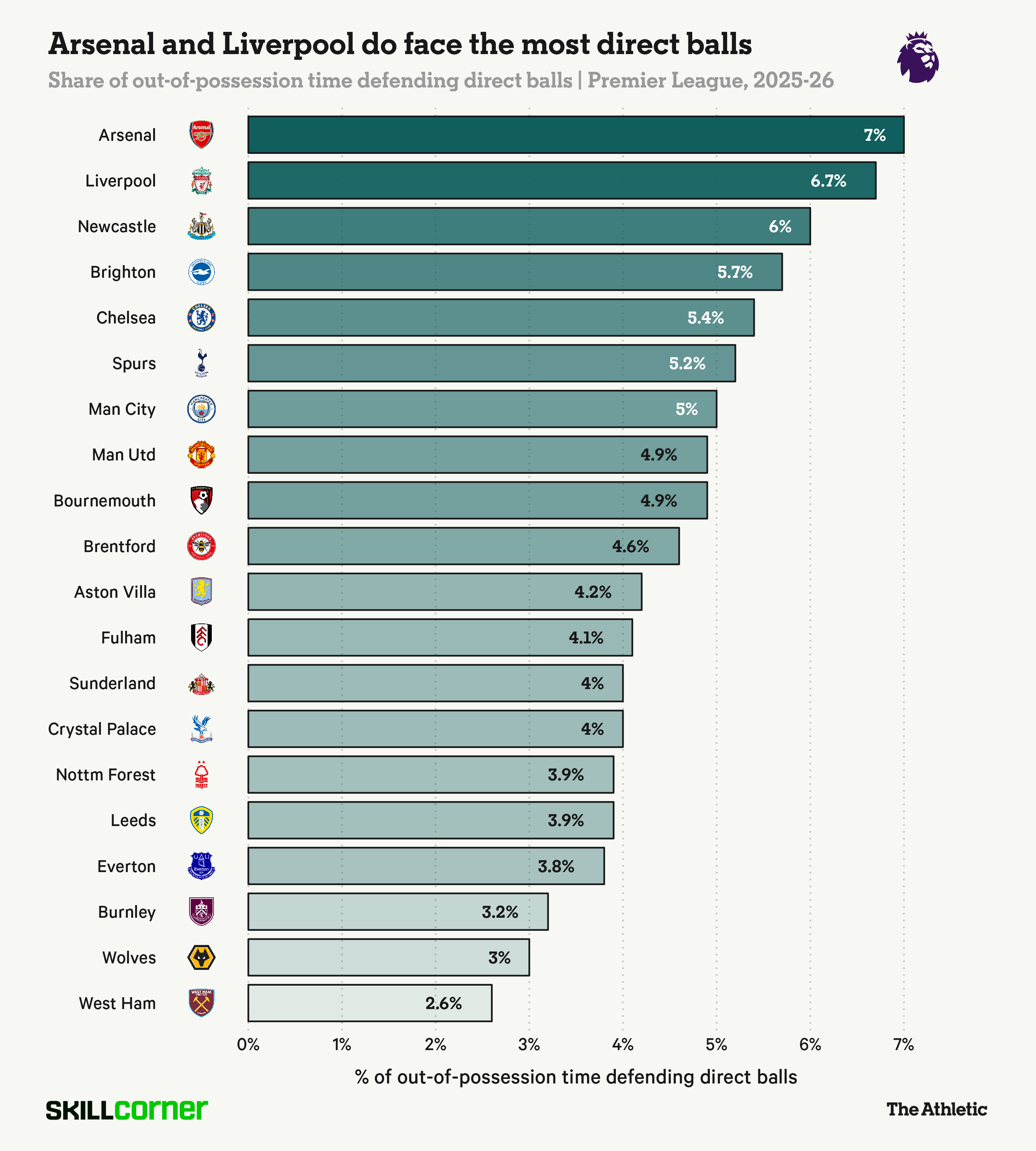

A second theme of Slot’s frustrations has been the volume of long balls his side have had to face this season. With teams becoming increasingly proficient at man-for-man pressing during opposition build-up, there is a greater tendency for opponents to bypass the press altogether with balls over the top when working the ball out of defence.

That is borne out in the numbers, with only Arsenal facing a higher share of time out of possession defending direct balls, defined as a pass of 32-plus metres without being a switch of play.

How these two teams deal with such directness is interesting.

On the surface, the numbers look strong for Liverpool, who have the highest aerial success rate in their defending half thanks to the commanding presence of centre-backs Ibrahima Konate and Virgil van Dijk. However, Liverpool struggled with their ability to win second balls in the first half of the season — conceding lucrative chances after failing to secure possession after the ball ran free.

Every aerial duel must be followed by a second ball, and Arsenal’s physical capabilities extend to the remaining part of the sequence.

Knowing that teams are more likely to go long, Mikel Arteta’s side are less suffocating in their high press compared with previous seasons — but they know they can wear teams down in other ways. Picking up on second balls and preventing the opposition from gaining territory from a single long pass is a key part of Arteta’s attritional approach.

An example of this can be seen in their recent game with Leeds United. A long ball from Karl Darlow sees William Saliba win the first contact, but the crucial anticipatory action is from Declan Rice, who controls the loose ball and secures possession to begin another Arsenal wave of attack. A single direct ball only plays further into the hands of the away side.

The Premier League has experienced a paradigm shift that is notably bigger than previous seasons. Some teams are evolving, others are doubling down, but the agricultural, out-of-possession component of the game feels more important than ever.

Thankfully, we now have the instruments to measure the differences.