It was a 3-minute, rage-filled lecture to politicians that thrust ex-cop Vincent Hurley into the centre of a national debate on gender-based violence.

Sitting in the audience of a Q+A episode, the criminologist and former hostage negotiator’s frustration boiled over.

It was the end of April 2024.

Days earlier, tens of thousands of Australians had rallied in grief and frustration against a sharp rise in gender-based violence, demanding action. Prime Minister Anthony Albanese declared it a “national crisis” during a speech at a Canberra demonstration.

Australians took to the streets calling for more action to prevent the violent deaths of women. (ABC News)

Watching politicians quibble over party policies on the national broadcaster — in this context — fuelled Dr Hurley’s retort.

“How dare you!” he said, addressing senators Murray Watt and Bridget McKenzie, and then-NSW opposition leader Mark Speakman.

“How dare you … go into politics, in an environment like this, when one woman is murdered every four days, and all you … can do is immediately talk about politics.

“For God’s sake, how long do we have to listen to politicians like you … high-horsing about?”Loading…

Behind the emotional address was nearly 30 years spent at the front line of family and domestic violence — and a fervour to fix the system failing victim-survivors.

‘It was domestic after domestic’

Dr Hurley’s first posting after graduating from the police academy in the 1980s was to Sydney’s outer north-western suburbs, where responding to domestic arguments and violence was seemingly endless.

“It would’ve been 80 per cent of police work,” Dr Hurley told Richard Fidler on ABC Conversations.

On one occasion, he and his colleague were called to 20 different “domestics” in a single night.

“It was just domestic after domestic after domestic,” he said.

Family and domestic violence support services:Other resources that can help:WIRE: 1300 134 130Victims of Crime (or your state or territory’s Victims of Crime service): 1800 819 817If you’re in immediate danger, call the police on triple-0

For Dr Hurley, it felt like futile work, with inadequate mechanisms to protect women.

“There’s no way, when you think about it now, that you could ever solve anyone’s problem about a woman who was being flogged, and that’s what it is,” he said.

While responding to these incidents, he was shot at, punched to the ground and had a young girl die in his arms.

However, Dr Hurley says it’s not the violence that sticks with him most. It’s the traumatised victims — and the lifelong impact of the brutality they survived.

“What a waste of a human life,” he said.

“That young girl, and all the hundreds of thousands of victims throughout Australia — whether they be boys or girls, or mums or aunties or grandmothers, who are subject to horrendous violence — their true potential in society will never be known because they are coerced and controlled by some shithead male.

“It’s beyond tragic.Their life could be so much better and society could be a much better place.”Violence dismissed as ‘private’

After decades responding to gender-based violence, Dr Hurley believes in the power of early intervention.

Along with his academic work, he volunteers at Sydney high schools, speaking with senior students about unsafe relationships and the high rates of violence against women.

Stream Vince Hurley on his life as a police hostage negotiator

His aim is to influence young people and their “moral compass”, to teach respect, challenge harmful gender stereotypes and ultimately prevent violence before it starts.

It’s through this work that Dr Hurley has noticed a concerning viewpoint about domestic violence among some 14-to-17-year-olds.

“That’s when boys generally start developing personal relationships, whether it be with someone in the same sex or someone in the opposite sex, that’s when they start forming their views,” Dr Hurley said.

“They see domestic violence as a bit of a private crime.

“The word ‘domestic’, in their minds, insinuates a private argument between Mum and Dad or Mum and a partner.”

It’s because of this that Dr Hurley is calling for the terminology around domestic violence — when abuse occurs in intimate partner relationships — to be simplified.

“If I had my way, I would remove the word ‘domestic’ from that phrase, ‘domestic violence’ … and just have straight out ‘violence against women and girls’, because that’s exactly what it is.

“The word ‘domestic’ softens the crime. It doesn’t bring home the brutality or the maleness in the crime.

“It doesn’t matter if it occurs at home. It doesn’t matter if it occurs in the shopping centre, down the street or at the footy ground. It’s just straight-out violence.”

A shift in policing

While gender-based violence still prevails, Dr Hurley says the police response has evolved to be “dramatically better” since he started as an officer.

He attributes this to a cultural shift in the police force, legislative changes and a pro-arrest policy to improve the safety of victim-survivors.

Next steps when someone says they are experiencing DV

Even so, Dr Hurley regrets he wasn’t able to do more during his time to keep women safe.

While women’s refuges existed, underfunding meant there were few of them and their locations were kept secret, even from police.

“There would’ve been women that I left — and children — in really vulnerable situations. I have no doubt, after we left, they would’ve been flogged,” he said.

It was an era, Dr Hurley says, when new police officers graduated after just 12 weeks of training and without any domestic violence education.

“And now they have about 18 months of training. So they’re certainly more aware of social issues — as they should be,” he said.

Vince Hurley in 1985, four years into his policing career. (Supplied)

While domestic violence was a common thread throughout Dr Hurley’s career, he also worked in police rescue, the undercover drug squad as well as the child sexual assault unit.

But some of the experiences that have lingered most are from his eight years as a police negotiator — where much of his work remained at the front line of family and domestic violence.

Most commonly, he was called out to sieges involving family members being held hostage or to talk with someone experiencing a mental health crisis.

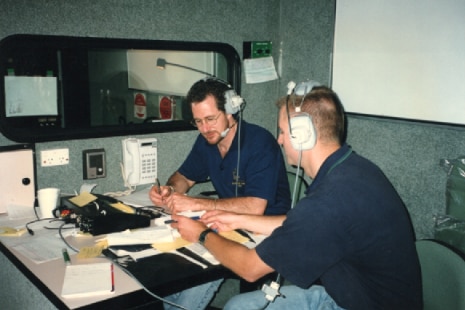

Vince Hurley (left) and his colleague in a mobile command post, negotiating with a man to exit his home. (Supplied)

“There was a siege or a suicide intervention every three to four days,” Dr Hurley said.

Working with strangers in crisis, where underlying trauma and mental health issues were often involved, Dr Hurley relied on compassion, empathy and active listening to de-escalate tense situations.

The night that still lingers

For Dr Hurley, honesty and a non-threatening approach were essential for a positive outcome.

This was the case one winter’s night when he was called to talk to a young woman on the verge of taking her own life.

“Once they start telling you the story, you sit back and you listen and you try and pick up some positives from it,” Dr Hurley explained.

“You give them hope. You’re not lying to them and you don’t be disingenuous about it.”

If you or anyone you know needs help:Suicide Call Back Service on 1300 659 467Lifeline on 13 11 14Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander crisis support line 13YARN on 13 92 76Kids Helpline on 1800 551 800Beyond Blue on 1300 224 636Headspace on 1800 650 890ReachOut at au.reachout.comMensLine Australia on 1300 789 978QLife 1800 184 527

Eventually, to Dr Hurley’s relief, he was able to help the woman change her mind.

But what she did next came as a surprise, and Dr Hurley has never forgotten it.

“She gave me a big hug, which was really, really rewarding,” he said.

“I can still picture it now because that was lovely — that was amazing.”

It was the first and only time someone reacted that way in Dr Hurley’s eight years working as a negotiator.

Life out of the uniform

In 2010, after 29 years of service, Dr Hurley was medically retired from the NSW Police Force.

He’s spent his career since working in academia, earning his PhD in criminology, teaching university students about criminology and policing, as well as developing domestic violence policy for the state government.

In spite of the serious and life-threatening situations he encountered as a police officer, Dr Hurley fondly remembers his police career.

“I miss the action. I miss putting on the uniform — that was part of my identity,” he said.

“I do miss the camaraderie … the dark humour. I’ll crack jokes at work … but they won’t find it the slightest bit amusing.”

And, years on, he often contemplates how life has panned out for the people he helped — the woman that winter’s night, in particular.

“I still wonder whatever happened to her,” he said.

“You walk into someone’s life, not knowing a single thing about them, and then you resolve the situation … she was taken to hospital for assessment — and I went home to bed.

“I never heard from her again — not that you’d expect to — but to this day, I still wonder what she’s doing.”

Stream Dr Vince Hurley’s full Conversations interview via the ABC Listen app.