This is a story about a major global business with a problem: sports.

The issue sports have is a) they can’t control who wins, but b) who wins makes a huge difference to the product they are selling to fans. A popular champ makes for a popular sport, and many factors go into making a celebrated global champion — though the biggest and simplest is where they are from.

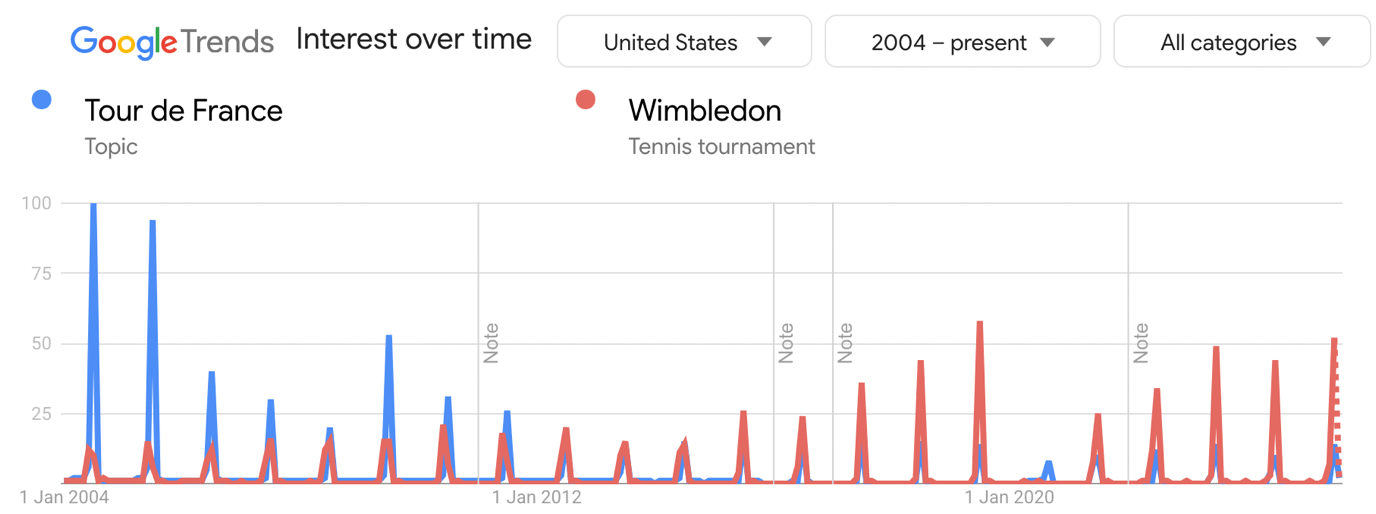

Consider this graph of search interest from the US in the Tour de France. They loved it back when Lance Armstrong was winning (2004, 2005). They do not love it now.

Cycling, in 2025, has a microstate problem. The greatest cyclist of this era — a guy with a chance to become the greatest of all time — is Tadej Pogačar. From Slovenia, population 2 million. His great rivals include Primoz Roglic of, you guessed it, Slovenia too.

Related Article Block Placeholder

Article ID: 1209900

Of the world’s top 10 cyclists, Slovenia, Belgium and Denmark are well-represented. This bodes ill for the global reach of professional bike riding. Media coverage will not follow cyclists that few care about. TV rights, sponsorship, media coverage, grassroots participation — all of these will wane.

Independent. Irreverent. In your inbox

Get the headlines they don’t want you to read. Sign up to Crikey’s free newsletters for fearless reporting, sharp analysis, and a touch of chaos

By continuing, you agree to our Terms & Conditions and Privacy Policy.

The Tour de France just finished with Pogačar rampant. I barely watched, which is quite a contrast to 15 years ago, in the Cadel Evans era, when I was an eager viewer. Do I like sports, or do I just like watching Australians win?

I don’t want to say nationality is deterministic. I know half the people who began reading this story are already down in the comments telling me nationality doesn’t matter a jot to the enlightened viewer; that their favourite player of all time is the Czech Ivan Lendl or the Canadian Felix Auger-Aliassime; that there is an undeniable underdog excitement in the rise of a player from an unheralded country, like Tunisia’s Ons Jabeur.

To those rebuttals, I make a full concession: sport is a rich tapestry, with many glittering threads to appreciate.

People from all over the world loved Roger Federer and Usain Bolt; a loveable champ lifts a whole sport. Also many people love a sport because they themselves play it, or appreciate its rhythms and aesthetics. You can love a sport nobody else cares about at all, hold a pure passion for the activity. But mostly we enjoy sports as a sort of communal practice. Few shout alone.

Consider your interest in the women’s 400-metre track race at the Olympics. Did you care a great deal about the outcome in the year 2000? Have you thought little about the race since?

The problem for cycling can be seen in the following chart. It depicts the populations of the countries of the top 10 athletes in cycling each year. During a year when these athletes are from populous countries, the bar is tall. When Slovenia and Belgium dominate the podiums, the bar is shorter.

There’s a stark contrast in tennis, particular women’s. The number of Americans in the top 10 of women’s tennis is at a crazy high: of the top 10, four are Americans. There’s also a Chinese athlete.

Here you can see a population chart for the women’s tennis top 10 players. Despite Aryna Sabalenka (Belarus, 9 million) sitting atop the rankings, the number of people with a national representative is huge.

The number of American women in the top 10 of tennis right now is incredible and demonstrates how a champ can drive interest in a sport within their home country. The Serena Williams legacy is not only the trophies she won or the record viewership she commanded; it was also inspiring the next generation of top players from her country.

In this vein, men’s tennis will also be quietly pleased to have fresh champions that are from Spain (50 million) and Italy (60 million), not Serbia (6 million), with two male athletes from the US also lurking in the top 10. With the US Open beginning in August, tennis will be a big deal in America.

I described sport as a communal practice, and that communal aspect is mediated by TV and print coverage. What gets into the press? Players from populous countries.

Related Article Block Placeholder

Article ID: 1215661

As the global mass-media landscape shrinks to fewer global brands, a story on the tennis in The New York Times or The Economist makes an increasingly larger difference to global attention. The editors of these mastheads will commission those stories if Taylor Fritz (US) or Jack Draper (UK) make the final of the US Open.

Likewise, the streaming rights for tennis will be a bigger prize for an outfit like Netflix if Naomi Osaka (Japan) or Coco Gauff (US) appears regularly at the business end of tournaments.

This is why we can expect to be hearing more about tennis and less about cycling in future.

The organisations behind these sports no doubt recognise this pattern. Do they put their thumb on the scale for the athletes from big, rich countries? It’s worth watching out for. But even a thumb on the scale can’t overwhelm a champ of the singular quality of Pogacar. And that’s the problem cycling has.

How much of your interest in sport is based on nationality?

We want to hear from you. Write to us at letters@crikey.com.au to be published in Crikey. Please include your full name. We reserve the right to edit for length and clarity.