Participants and procedures

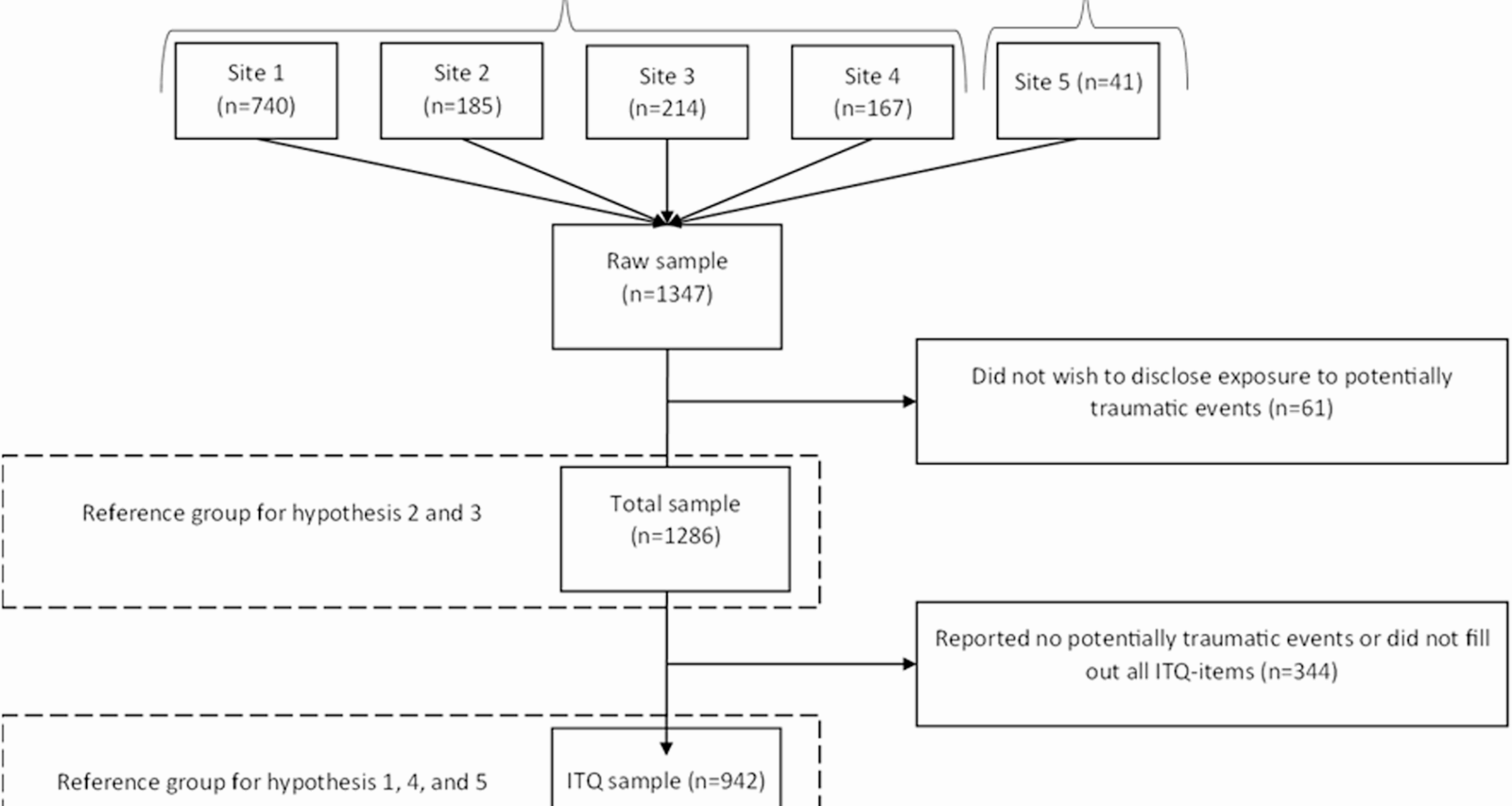

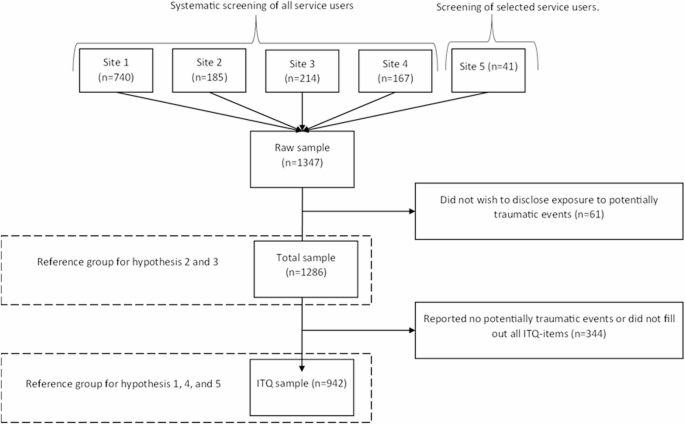

The study design was cross-sectional. Data were collected for 13 months at five sites in Denmark (from November 1, 2022, until December 29, 2023). Figure 1 displays the data flow of the project. Data were retrieved from structured interviews with adults who chose treatment for DUD or AUD at five Danish treatment centers. In Denmark, AUD and DUD treatment are separate offered by counsellors specialized in either AUD or DUD counselling, however both types of treatment are typically offered in the same treatment center. Individuals can seek treatment based on their perception of whether they want help for AUD or DUD. Thus, patients in DUD treatment may also have concurrent AUD, and vice versa [26].

Flow chart of participant recruitment

The five treatment centers participated in a larger research project that evaluated two PTSD treatment models in treatment for SUD and were situated in both rural and urban areas. One of the centers (site 5) offered heroin-assisted treatment only, whereas the remaining sites (site 1 to 4) offered specialized outpatient SUD treatment including OUD treatment. The five sites offered various SUD treatment modalities, including medication, psychotherapy, family counselling, and psychoeducation. All of the centers are public and free of charge and operate in close collaboration with the country’s social service and healthcare systems.

A total of 1347 adults were interviewed as part of a structured intake screening at the treatment centers. Due to structural and organizational differences in treatment, the screening interview was consistently done at the DUD treatment sites but less so at the AUD treatment sites, which meant that, in our study sample, 69.5% came from the former versus 30.5% from the latter. Also, at site 5, only individuals who were assessed to be able to participate in a psychotherapeutic treatment course (n = 41) were screened for PTSD. This assessment was done by the primary counselor and was based on clients’ motivation, ability to focus, and level of abstraction.

Measures

Data for the present study were retrieved from AdultMap interviews [27]. AdultMap is a Danish structured screening interview consisting of 70 to 90 items (depending on responses) that is specifically developed for SUD treatment. Topics in the interview are living conditions, mental health and behavior, physical health, substance use, social network, adverse experiences, and function level. AdultMap is widely used for SUD treatment in Denmark and has been implemented in 62 out of 74 municipal treatment centers in Denmark. The primary aims of the interview are to assess current barriers, needs, and resources to offer the most appropriate treatment possible. The questions used in the present study (demographic data, trauma exposure and substance use) are part of the current version of AdultMap. The trauma symptom items in the present study were implemented for the study period and in the five included treatment centers only. Interviews were conducted at the start of treatment by counselors.

Demographic data

Demographic factors were gender (male or female as indicated by social security numbers); age; treatment type the client chose (AUD or DUD); employment status (employed, in training, in school, or none); source of income (financially supported via full- or part-time occupation, educational support or governmental support, early retirement, or no income nor financial support by relatives); and living situation (stable or partly stable vs. unstable such as homeless, living in an institution, or incarcerated). Pre-existing psychiatric disorders were reported for the following disorders: depression, bipolar, anxiety, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), personality disorder, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), autism spectrum disorder, schizophrenia, or psychosis. Participants were asked to only report diagnoses given by a psychiatrist. The metric was total number of pre-existing diagnoses.

Trauma exposure was assessed using a single item of a non-specified stressful experience, as well as five specific categories of potentially traumatic experiences (i.e., accident, sexual abuse or assault, physical or psychological violence, life-threatening illness, sudden accidental death, and other very stressful or violent experience). These specific categories were selected based on prior research indicating that they are the most common types of traumatic exposure previously identified in the general population [28]. An almost identical event checklist was used in a Danish ITQ validation study [25], the only difference being that a seventh item (natural disasters) was not included in the present study, as natural disasters are rare in Denmark. For the trauma exposure check list, participants were able to reply “I do not wish to disclose”.

Each trauma type reported was scored dichotomously with 1 = directly exposed or witnessed and 0 = not directly exposed nor witnessed. For trauma exposure, timing of exposure was recorded as (1) throughout the childhood, (2) in adulthood, or (3) both in childhood and adulthood. Hence, participants that were exposed in childhood but also in adulthood to any or different types of trauma would fit in category 3, whereas participants exposed to any type of trauma either in childhood (until 18th year of age) or in adulthood (after 18th year of age) only, were listed in category 1 or 2, respectively.

ICD-11 PTSD

ICD-11 PTSD symptoms were assessed using a Danish translation and validated version (Hansen et al., 2021) of the International Trauma Questionnaire (ITQ) [29]. The ITQ is a 12-item validated self-report measure developed for assessment of ICD-11 PTSD and Complex PTSD. The concurrent and discriminant validity of the ITQ [30, 31], along with the factorial validity of the ITQ across different countries and cultures, including Denmark, has been demonstrated in several studies [24, 25, 32]. Only the 6 items for ICD-11 PTSD were used in the current study. In the ITQ, the six PTSD items are accompanied by three items measuring associated functional impairments in the domains of social, occupational, and other important areas of life. Respondents that endorsed at least one of the specific potentially traumatic events are asked how much each PTSD symptom bothered them in the past month, with scoring from 0 (“not at all”) to 4 (“extremely”). Symptoms are considered endorsed at two (“moderately”) or more. To meet criteria for PTSD, one symptom is required in each of the clusters for re-experiencing, avoidance, and sense of threat, as well as a score of two or more on one of the three functional impairment questions. As previous studies showed differential treatment response between individuals with clinical vs. subclinical [33] we wanted to include subclinical PTSD as a diagnostic construct in our analyses. Patients could meet criteria for subclinical PTSD if they had all but one PTSD symptom cluster plus had functional impairment [2, 3]; or if they met full PTSD criteria but without functional impairment. Cronbach’s alpha for the ITQ in the present study was 0.84 for the PTSD subscale.

Substance use severity

Alcohol use severity was measured by a total score on the AUDIT, a 10-item screening tool developed by the World Health Organization (WHO) [34]. The AUDIT assesses the amount and frequency of alcohol use, alcohol dependence, and problems related to alcohol consumption. Each item is scored from 0 to 4, resulting in a total score range from 0 to 40. The current study relied on cut-off scores established by the WHO whereby scores from 8 to 14 indicate hazardous or harmful alcohol-use, and scores of 15 or more indicate the likely presence of moderate to severe alcohol use disorder, corresponding to alcohol dependence [35].

Drug use severity was measured by self-reported use of cannabis, amphetamines, cocaine, MDMA, opioids, and other substances within the past 30 days. Responses were coded into a composite score ranging from 0 to 100 (number of days cannabis + number of days amphetamines + number of days cocaine + number of days MDMA + number of days opioids + number of days sedatives + number of days with other substances)/210 (the number of possible days with drug use) x 100. For example: number of days cannabis use (n = 20) + number of days cocaine use (n = 4): 24/210 × 100 = 11.4. The calculation for the severity is based on previous publications on Danish SUD treatment outcomes using the same measure e.g [36, 37].

Data analysis

The data were cleaned as per Fig. 1, and then we tested each of the five hypotheses.

Hypothesis 1

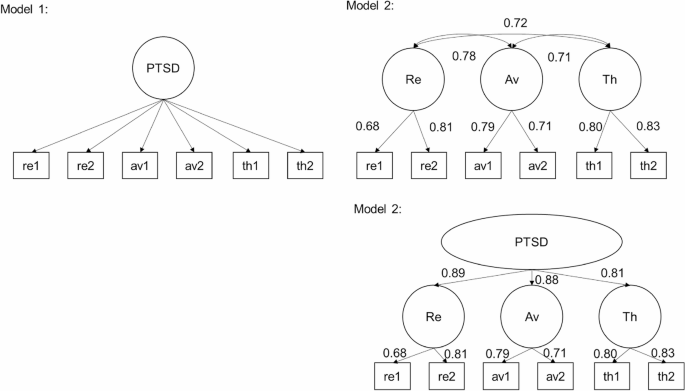

Two competing models of the latent structure of the ITQ were tested to examine whether the ITQ factor structure among substance users align with existing findings on the ICD-11 model of PTSD [32]. The first model tested was a one factor model, where all items loaded onto a single latent factor representing PTSD-severity. This model has 18 free parameters and nine degrees of freedom. The second model was a correlated first order model representing the segregation of ITQ-items into three correlated latent factors corresponding to the ICD-11 formulation of PTSD consisting of re-experiencing, avoidance, and sense of threat. This model has 21 free parameters and six degrees of freedom and is statistically equivalent to a one factor second order model where factor correlations are replaced by factor loadings of re-experiencing, avoidance, and sense of threat onto a latent factor of PTSD. Figure 2 displays the competing models. The model fit was evaluated and compared using a standard range of model fit indices. The model with the lowest BIC is preferred as long as other indicators support the fit of the model to the data. This includes CFI and TLI values above 0.90 or 0.95 for adequate or excellent fit, and RMSEA and SRMR values lower than 0.08 or 0.05 for adequate or close fit to the data, respectively.

Competing models 1 and 2 of the latent structure of the ITQ including standardized parameters. Note: Re = re-experiencing, Av = avoidance, Th = sense of threat. All factor loadings and correlations were statistically significant at p <.001

Hypothesis 2

We calculated descriptive statistics on each PTSD-symptom cluster and functional impairment as well as the total rate of positive screens for PTSD and subclinical PTSD, as described in Methods.

Hypothesis 3

Chi-square analyses were conducted to test the distribution of types of traumatic events across each treatment type, and independent samples t-test was used to evaluate differences in total number of traumatic events.

Hypothesis 4

Independent samples t-tests was used to compare PTSD-severity between DUD and AUD treatment.

Hypothesis 5

A series of chi-square analyses and ANOVAs, first on the total sample and then on AUD and DUD treatment samples separately, was used to test the significance of observed differences across probable PTSD-diagnostic status (no PTSD, subclinical PTSD, and PTSD) as well as demographic and trauma-related variables in each treatment group.

Analyses were conducted using Mplus version 8.81 and SPSS version 28. Missing data for trauma-exposure and ITQ-data was handled as stated in the beginning of the results-section for the different hypotheses. Missing data on other variables ranged from 18.8% for education over 6.7% for age to 0% for sex, income, living arrangement and N psychiatric diagnoses and was handled using casewise deletion.