TORONTO — Two years ago, on a sunny afternoon at Sobeys Stadium in Toronto, Jannik Sinner raised the Canadian Open trophy. Confetti showered the Italian as he lifted his first ATP 1,000 title, one rung below a Grand Slam, which proved a springboard to an exponential ascent that has made him world No. 1 and a four-time Grand Slam champion.

This year, Sinner didn’t set foot on the grounds. Sinner pulled out of the Canadian Open in the wake of his maiden Wimbledon title, citing an elbow injury suffered at the All England Club. Carlos Alcaraz, Sinner’s beaten opponent at Wimbledon, pulled out the following day. Novak Djokovic, the 24-time Grand Slam champion, also skipped it, as did Britain’s Jack Draper, who is nursing an injury.

Ultimately, four of the top 10 players on the ATP Tour didn’t play in one of its most prestigious events. Extend that to the top 20, and the list grows to six. While Alcaraz and Djokovic also missed last year, that was because of the 2024 Paris Olympic Games; Sinner lost to Russia’s Andrey Rublev in the quarterfinals.

The withdrawals came as the event joined the ranks of the other 1,000-level tournaments, aside from the Paris and Monte Carlo Masters, by growing from one week to 12 days in length. The Cincinnati Open, which follows the Canadian and begins this week, has grown in the same way. This left just a fortnight between the end of Wimbledon and the start of the Canadian Open, making it harder for players to recover, especially players such as Alcaraz and Sinner, who went to both the French Open and Wimbledon finals.

Next year’s Canadian Open will have the three-week gap back, but the 12-day format and 96-player draw will remain. Ben Shelton, the rising American, will be defending champion, after beating Karen Khachanov to win his first ATP 1,000 title.

The tournament says the absence of the biggest stars in tennis will be just a one-year blip, but in the wider context of tennis, the 12-day format remains a bellwether for the sport’s schedule conflict between volume and quality.

The origins of the 12-day format can be traced to the ATP’s “OneVision” plan. Predicated on growing prize money, sponsorships, ticket sales and TV rights by expanding the tour’s most prestigious events — the Masters 1,000s, named for the ranking points awarded to the winner — it was sold by chief executive Andrea Gaudenzi as an opportunity to “pursue new growth and focus on what matters most: the fans.”

“It’s Andrea’s vision for driving the sport,” Canadian Open tournament director Karl Hale said during an interview about the 12-day format, which has also been adopted on the WTA Tour at seven of its 10 1,000-level events.

“People want to see the top players play against the top players more often. He made his pitch about how important it is to our sport, and also how important it is for us as a sport to keep close to the Grand Slams and other sports,” Hale said.

Fans in Toronto did not get to see the top of the top players play against each other, and players higher up the world rankings — some of whom initially backed the plan when it launched — tend to focus on how the format has made the schedule too strenuous, because they are now going deeper in longer events than they did before. For players lower down the rankings, the change has given them greater opportunity to play in big events, and more chances to earn prize money and compete against the best.

Alexander Zverev, the top seed in the event who lost in the first round of Wimbledon and took a month off before beginning the North American hard-court swing, called it “not beneficial for top players.”

Shelton agreed, but from a different perspective. The 12-day structure means players get days off between matches, which some prefer because it echoes the format of Grand Slams. But it also stifles opportunities to develop match rhythm, which is particularly important in a tournament like the Canadian Open, because it marks the transition from grass courts to hard courts, as well as a change from some of the heaviest balls on tour, the Slazengers, to one of the lightest, in the Wilson U.S. Open balls.

“The level is definitely higher in those one-week tournaments, when you’re playing two out of three sets and you’re playing back-to-back days and you get into a consistent rhythm of playing,” Shelton said.

“It’s tough (in this format) with the start and stop, and I think that a combination of those things is probably what players are talking about and what’s throwing a lot of guys off.”

Taylor Fritz, who reached the semifinal in Toronto before losing to Shelton, struggled to control the ball on the quick courts earlier in the tournament.

“Typically, when I’m missing shots, I know exactly why I’m missing, I know what I did wrong,” Fritz said in a news conference. “The first couple days I was here, and even in my first round match, there’s balls going 10 feet long that feel exactly the same as the one that was just right before that went in.”

Fritz made the semifinals of this year’s Canadian Open. (Matthew Stockman / Getty Images)

The Canadian Open’s run into the Cincinnati Open and then the U.S. Open is also a contributing factor to players withdrawing. On the men’s side, it is the second stretch of the year in which two Masters 1,000s are played back to back, following the Madrid Open, Italian Open, French Open stretch in the clay swing.

“This is a tough part of the year because there’s not really any weeks that make sense to take off,” Fritz said.

Others thrive on the condensed calendar. It is Frances Tiafoe’s favorite stretch. Tiafoe, who last year reached the U.S. Open semifinals, plays in his home tournament at the Citi Open in Washington, D.C, before traveling to Canada to play in Toronto or Montreal; his girlfriend Ayan Broomfield is from the former city.

Then he heads to Mason, Ohio, before competing in his home Slam in New York City.

“When you’re happy off court, you’re happy on court,” Tiafoe said in a news conference. “I love being in North America, close to my family. My friends can come out. I just feel so comfortable and it makes me want to compete, makes me want to go hard.”

Hale, who said he was disappointed when he was informed that Sinner and Alcaraz had withdrawn, discussed the tournament with Gaudenzi in meetings in Toronto. Hale said that the discussions with Gaudenzi and ATP board members weren’t reactive to the withdrawals and that more conversations are scheduled at the U.S. Open and Turin for the ATP Tour Finals.

Hale said that both sides discussed “improving the situation” around the 12-day model, which will be aided by the three-week gap between Wimbledon and Canada next year. According to Tennis Canada chief executive Gavin Ziv, the conversations with the tours and other tournaments revolve around “improving the whole health of the tour.”

“We got to work on some of the kinks in the schedule and there are things to work on there for sure to make it more successful for the future,” Ziv said. “Let’s look from start to finish, and what changes will they make along the way to try to get a healthier calendar for everyone.

“For the tournament to be more successful, will the players get enough rest they need throughout the year?”

Most fans who attended the event were more focused on who was there than who was not, especially when supporting players from their own country.

Aussie fan Ryan Kirwan traveled from Sydney to Toronto to cheer on Alex de Minaur and Alexei Popyrin, and focused on the “exciting matches involving players worldwide” that he did get to see.

John and Manuela, a couple from Atlanta, Ga., also attended the Canadian Open for the first time. Visiting their niece Manuela in Toronto made going to the tournament a no-brainer, and Shelton’s run to the final made sitting courtside an evening to remember: One of John’s friends was the youth coach for Shelton, who was born in Atlanta.

Edward, a young fan from Cincinnati, went to his first final at the 2023 edition of the Cincinnati Open, when Djokovic and Alcaraz produced a three-set classic. He purchased tickets to the Canadian Open in March, not knowing who would make the final. It didn’t matter who was playing, according to Edward. He wanted to watch world-class tennis.

Seven of the eight quarterfinalists in Toronto were seeded players, and the top two seeds advanced to the semifinals. Last Sunday, all four round-of-16 singles matches on Centre Court went three sets, as did the final, which concluded after two hours and 47 minutes.

The matches may be long and close, but for some fans, the players in the draw just don’t have the same gravitational pull.

Just ask Prodip and Motha, a couple from Toronto, who bought tickets in May with the hope of seeing Sinner and Alcaraz. While they both attended Thursday’s final, they were upset that they didn’t see the top two players on the ATP Tour and the championship match being late on a work week.

“Why is it on a Thursday?” Prodip asked.

Baljot and Paul, two friends who also attended the Canadian Open final, are frequent spectators at the event. Two years ago, they watched Alcaraz play Shelton and Tommy Paul. They remember the packed stadium and the roars for Alcaraz’s dazzling points. Both dismiss the 12-day format.

“Playing back-to-back 12-day events is stupid,” Baljot said.

The women’s event, this year held in Montreal and also 12 days, was less affected by withdrawals. Only world No. 1 Aryna Sabalenka skipped it, and the top seeds went out not with injury, but through players taking them down. Come the end, Victoria Mboko, the 18-year-old Canadian wild card, beat former world No. 1 Naomi Osaka in three sets for her first WTA Tour title.

For Hale, while the event was a success, the recognition remains that the players “are the product.”

“Without them, there’s no tournament,” he said.

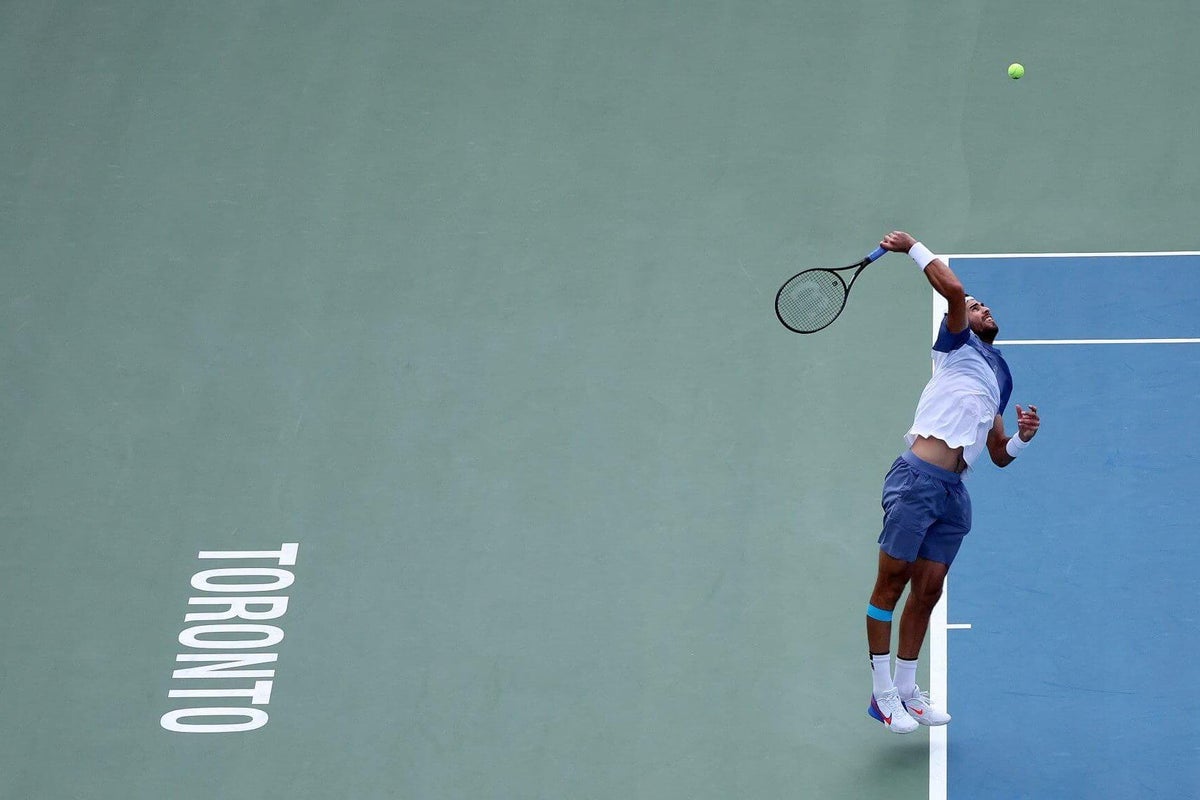

(Top photo of Karen Khachanov: Steve Russell / Toronto Star via Getty Images)